The Battle of Monte Cassino, also known as the Battle for Rome, was a series of four military assaults by the Allies against German forces in Italy between January and May 1944, in one of the bloodiest battles of world war two.

The month of May 2024 marks the 80th anniversary of the end of the Battle of Monte Cassino, a significant moment in the WW2 Italian campaign.

The final breakthrough on 18 May enabled the Allies to advance north to liberate Rome on 5 June 1944, marking the beginning of the end for the German occupation of Italy.

This Sunday 19 May we will host a commemoration at the Monte Cassino @CWGC cemetery, part of the #MC80 activities.

https://t.co/9SXURifj1o@UKDefenceItaly pic.twitter.com/CvSBqsE3CJ— UK in Italy (@UKinItaly) May 13, 2024

Here we republish a feature article by eminent British archaeologist Richard Hodges, past president of The American University of Rome, written to mark the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Monte Cassino in 2019.

Driving past Monte Cassino many years ago with the late Mark Pluciennik, professor at Leicester University, and one of the most cerebral archaeologists I have known, I pointed out the Benedictine monastery. Mark replied with words I’ve never forgotten:

“My father was with the Poles who captured the monastery, and my uncle, his brother, as fate would have it, was with the Germans on top. The battle unwittingly pitched brother against brother.”

His words have long lingered in my mind and over the years I have met many survivors of this historic battle between the Allied and Axis forces in 1944. Through them I have become familiar with oral histories and the battlefield archaeology. None spoke well of the experience, though all the Allied veterans recalled with pleasure and gratitude their encounters with the long-suffering Italians. Liberating them justified the struggle.

The battle lasted from December 1943 until May 1944, led to the comprehensive destruction of the town of Cassino, and at the conclusion, the main objective – defeating the formidable German army – was eschewed in favour of the liberation of Rome. The impact of the battle has left an indelible mark on Italy and in the minds of many, while the performance of some of the generals was in the end reminiscent of the later rather than the earlier Roman empire. All of this can be discovered on the ground. There are archaeological remains galore but, unlike the Normandy battlefield of June-July 1944, it is not organised and really should be.

The battle for Monte Cassino embraced the mountains from the Tyrrhenian to the Adriatic Sea. One particular hotspot was, as it happens, where Mark Pluciennik and I were excavating the early mediaeval monastery (9th-11th centuries) in the 1980s and 1990s, S. Vincenzo al Volturno, due east of Monte Cassino. Here multi-national forces assembled to assault the Abruzzi mountains, known locally as the Le Mainarde. The excavations revealed only one possible legacy from this tumultuous era: the skeleton of a young woman interred in a shallow grave in the remains of the ninth-century refectory. Local workmen excavating with me clearly knew something about this homicide. Ignoring my instructions to record the individual, she was hastily removed without ceremony.

Archaeology and history

This act revealed how raw the bitter wartime struggle remained, 40 years afterwards. None more so than for the monks of Monte Cassino. As long as we stuck to archaeology and history, our relationship at S. Vincenzo with Monte Cassino’s monks was fine (the monastery owned part of the land we were excavating).

Mention the war, and they all but spat with a lingering distaste. The Allied bombing that destroyed the monastery of Monte Cassino on 15 February 1944 was a crime against humanity, I was told more than once. Any mention of the occasion, and the elfin and normally genial archivist, Don Faustino, was transformed; his deep-seated anger boiled over. So, on an occasion when in Monte Cassino’s capacious archive a British diplomat friend asked Don Faustino about the battle, the learned monk snarled about the British and added, by way of taunt, how grateful the monks were to the Germans who transported the precious archive and library to safety long before the battle started.

Startled, my friend was about to give as good as he had got when the old abbot, Don Martino Matrinola, slipped into the archive. Don Faustino visibly retreated a step. The abbot, bent and thin, conveyed an immediate eminence. Far from senescent, his beady eyes focussed upon me and he asked about a unique, ninth-century coin I had discovered at S. Vincenzo and which he had caressed the previous summer in his long, claw-like fingers. I responded and, gauging the twinkle in his old eyes, introduced my diplomat friend as someone who was curious about the infamous bombing.

“I was in the monastery, I was Abbot Damiano’s secretary,” he said without a shift in tone. “What would you like to know?”

I hastily shaped a simple question to evade Don Faustino’s dismay. And so, Don Martino explained, the abbot and he and a handful of monks as well as hundreds of refugees had sought safety in the deep mediaeval bowels of the largely baroque monastery. As soon as the bombing had finished, they had fled down the mountain, guided by German officers.

“Were there Germans in the monastery and guns, tanks?” my friend eagerly enquired.

“Ah,” the old monk responded without missing a beat, “you should read our report made that morning to His Holiness [the pope]. It’s part of the papal record. There were indeed Germans here.” With that his mind found sanctuary in his memory of my little silver coin and he muttered more about it before shuffling off into the cloister.

I recall this moment in the archive because I had touched history.

The Battle

The battle pivoted around the monastery of Monte Cassino because the home of the Benedictines commands a high promontory over the old Roman road, the Via Casilina. This follows the valley from Rome to the Bay of Naples. At the foot of the hill sits ancient Casinum. Its most conspicuous monument is the over-restored Roman theatre next to the modern museum at the foot of monastery hill.

Here in December 1943 the Germans commanded by General Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin, an Oxford Rhodes scholar, created a fortification that extended west to the Tyrrhenian Sea near ancient Minturnae (modern-day Minturno) and east over the mountains to the far Adriatic Sea. Close this road, von Senger rationalised, and the Allies would be unable to take Rome. The Allies were ill-prepared for the obstinate German tactics, prompting a bi-passing operation at Anzio. By landing troops near Rome on the beach at Anzio on 22 January 1944, the Allies hoped to encircle and eliminate the Germans and thereafter advance swiftly through Italy, Churchill’s so-called “soft underbelly of Europe”.

The sea landings were unopposed and reconnaissance troops managed to drive into Rome. However the Allied commanders then prevaricated and dug in, and the Germans rapidly brought up troops to attack; what happened next was a grotesque battle in the marshland around the beach-head until May.

The prevarication came at even greater cost. The Allied offensive against Monte Cassino was intended to suck German troops from Rome to Cassino, creating the vacuum the Anzio landings might exploit. The battle involved crossing the rivers immediately west of Cassino on 20 January on the eve of the landings. The British just succeeded in traversing the Garigliano river but the Texas Rangers were massacred while attempting to cross the Rapido river close to Cassino by the German Panzer division entrenched immediately beyond the river.

It was a taste of things to come. This first battle successfully diverted German troops from Rome but the opportunity was eschewed and so started the slogging trench warfare.

Allied troops pressed through Cassino town and began a cat-and-mouse battle with the enemy. Trapped in and around ancient Casinum in wet wintry conditions, the British commander of the 4th Indian Infantry Division, General Francis Tuker, who believed that parts of the hilltop monastery were occupied by Germans with armour, asked for aerial bombing to destroy the monastery. After a fierce debate among the Allied commanders the bombing was undertaken with very little warning by US planes on 15 February 1944. The aftermath, though, made the monastery an impregnable redoubt.

Operation Dickens

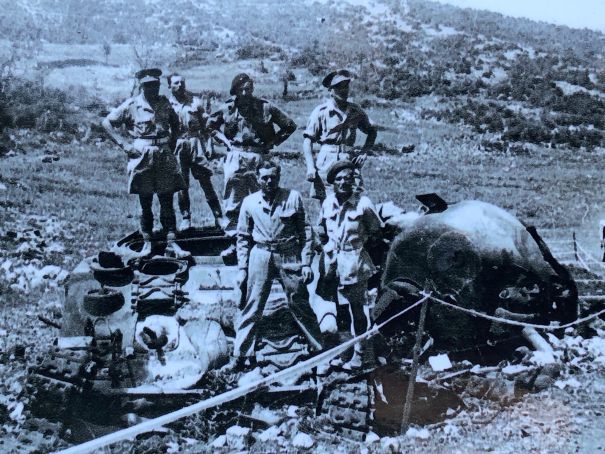

The third battle involved a frontal assault while a road – the Cavendish Road – was cut around the contours behind the monastery to facilitate a bold Allied pincer movement using armour. This battle – Operation Dickens – lasted between 15 and 24 March. Maori crews in Sherman tanks advanced in single file up the steep track. Terrified at first, the German defenders then realised that the American-built tanks were not supported by infantry. Boldly, the defenders knocked out the leading tanks, and so paralysed a dozen or so in their rear.

The last battle in 11-23 May 1944 was colossal in scope. After an immense artillery barrage from Allied guns aimed at the monastery and Germans in its surroundings, Allied troops pressed on all fronts, still aiming to encircle the German army. The frontal attack was born by the Free Poles (including Mark Pluciennik’s father), who heroically overwhelmed the monastery’s defenders. No less significant were the French colonial troops, who traversed the high mountain country above Minturnae (Minturno) west of Cassino, intending to descend upon the rear of the Axis army. Von Senger astutely recognised the threat and retreated.

His army should have been ensnared at Valmontone (below ancient Artena) by the Anzio divisions breaking out of the beach-head. Instead, General Mark Clark – against the plans of the British commander of the Allied forces in Italy, General Harold Alexander – sought his triumph and diverted his forces to Rome, parading like legions past the Colosseum, ensuring on the eve of D-Day that he was the first Allied commander to capture an Axis capital. This allowed von Senger’s German divisions to retreat east of Rome and to resist the Allies through central and northern Italy until April 1945.

The battle of Monte Cassino – or rather the four battles – was a Pyrrhic victory. Thousands perished and the ancient monastery of Monte Cassino had been blown to smithereens.

Monte Cassino

Monte Cassino attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors. Poles, in particular, pay homage to the exquisitely arranged cemetery in the valley immediately east of the monastery that commemorates those who ultimately vanquished the German defenders. Few monuments exceed this cemetery in paying tribute to the heroism and tragic inhumanity of war. It is as well to pause in this mass graveyard before rediscovering a quotidian rhythm in the formidable monastery that overshadows it. There are also moving Commonwealth and German war cemeteries close to Monte Cassino.

St Benedict founded his monastery in an ancient hilltop site. A massive Samnite (Iron Age) fortification encircles the crown of the hill, the mediaeval and later monastic walls nestle inside its great polygonal stonework. This fortress speaks volumes about the age when archaic Rome was vying for control over central Italy. Inside these cyclopean walls, in excavations made after world war two, remains were found of a Samnite and subsequent Roman temple, dedicated probably to Hercules. In time the temple became an outlier of Casinum, the affluent Roman roadside town at the foot of the hill that, with the defeat of the Samnites, succeeded the cyclopean fortress.

Quite how Benedict made use of the earlier temple as he created his sixth-century monastery is not known. Numerous finds are on display in the monastery’s museum. Post-war excavations, following the bombing, discovered the footings of one of Benedict’s churches, believed to be St Martin’s. Its ground plan is discretely marked out with neat stones in the outer cloister immediately after entering the monastery today. On the far side of this first cloister lies the locked glass door down to the old ceremonial entrance. Peep through it and along the walls you’ll see some of the hundreds of early mediaeval tombstones found in excavations after the war.

Post-war

The post-war re-building programme is vividly described in a new exhibition held in an annexe to the museum, just off the monastery’s cloister. It tells a remarkable story. Lasting over a decade in the 1940s and 1950s, with American support, the early modern monastery in all its baroque glory was lovingly restored. It was a miracle of sorts. A key person in this rebuilding was Don Angelo Pantoni, an engineer by training and passionate archaeologist. This restless monk had endured the siege and spotted his chance in the aftermath.

With haphazard methods, but huge dedication, he excavated wherever he could and published a series of monographs on the monastery’s origins. I knew Don Angelo in his 80s when he visited my excavations at S. Vincenzo. Deaf from birth, twinkling eyes, eccentric in every way in his dishevelled habit, his passion was making sense of the past. Thanks to his antiquarian exactitude, the destruction of Monte Cassino seems barely conceivable today as you climb the steep flight of steps, conceived originally by Abbot Desiderius in the mid to late 11th century, up to a closed outer atrium.

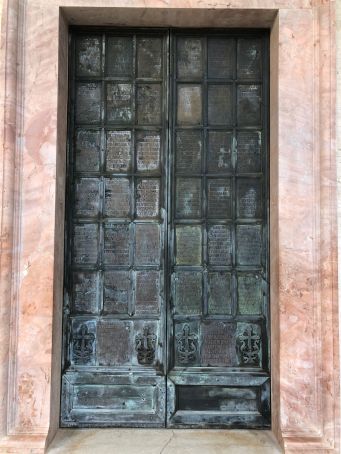

One great work of art survives world war two and from this abbot’s re-envisioning of the monastery: the central bronze door made in the 1060s by a Byzantine master in Constantinople. The upper 36 panels are inscribed with names of churches and lands, dependencies of the monastery. Below are two panels bearing dedicatory inscriptions, each flanked by a cross in relief. It bears witness to the abbey at its zenith, before the crusades began, on the main pilgrimage route from northern Europe to the Holy Land.

Inside the basilica is a faux baroque church. This replicates the great church that Napoleon Bonaparte sacked in 1799. Before its post-war resurrection – so to speak – the indefatigable Don Angelo excavated in search of Benedict’s first church. What he found were the foundations of the ninth-century abbey-church of Abbot Gisulf, one of the great figures of the age of Charlemagne. Around its outer walls were block-built tombs with bases made from tiles pierced with holes to permit the bodies to decompose gradually.

Museum

The museum is a treasure-house. Apart from the new, visually striking annexe dedicated to the bombing and re-building, there are rooms full of the monastery’s copes, mitres, paintings, sacramental paraphernalia, and above all some of the great books that are the cornerstone of western civilisation. If you select just one, pause at the open page of the 11th-century encyclopaedia, De rerum naturis (On the nature of things), an opulent copy of the work by the 9th-century scientist and Benedictine abbot, Hrabanus Maurus.

How did these treasures survive? Don Faustino, the archivist at Monte Cassino, was never slow to answer this rhetorical question. General von Senger, aware of the huge risk he was taking, had everything transported to Rome and Perugia a month before the Allied vanguard arrived on his horizon.

Today the story of the bombing may seem like distant history in the modern monastery. Not so in the town of Cassino below. None of its historic churches survived the battle. Instead, the busy little town has an anonymous feel to it, the result of expedient post-war reconstruction. Only its museum, half a kilometre up monastery hill, and the refurbished mediaeval castle with its pencil thin tower come close to recalling the rich heritage of this place before 1944.

Cavendish Road

Take the SS 509 to S. Elia Fiumerapido Sora from the centre of Cassino and after 3 kms, immediately after crossing a river, turn left on the Via Orsala and follow the narrow lane to a sign that marks the beginning of the Cavendish Road. Made after the failure of the second (February) battle, it was the brainchild of the New Zealand division. Its engineers widened an existing mule-track to enable Sherman tanks to approach the monastery from the rear. This creative adventure on 19 March 1944 came to nothing, but today it is by far the best way to get a sense of the terrain that gave the German defenders a huge advantage.

It is a three-hour round trip on a track to the monastery, which is flagged the whole way. The climb is steep and the track has been worn to rubble for the first two kms. But the views of the mountains to the east are peerless. The path passes through thick, low woodland, but press on because at the far end is a memorable piece of archaeology. A Sherman tank has been transformed into a memorial to the Polish 4th “Scorpio” Armoured Regiment who took the road in May 1944.

Beyond is a farm where the monastery makes its own beer. It overlooks the formidable remains of the monastery of S. Maria dell'Albaneta. Founded in the 10th century, it was essentially an overspill monastery for Monte Cassino at its apogee. Young Benedictines like Thomas Aquinas were first initiated in this serene spot. Today American trucks from the battle occupy the spot where its cloister once was. The path is now a road, graced with stone memorials to the Poles. Fittingly, the Cavendish Road trail terminates at the Polish cemetery in the shadow of the monastery, a gleaming citadel.

By Richard Hodges

Richard Hodges, an eminent archaeologist, was president of The American University of Rome from 2012-2020 and director of the British School at Rome from 1988-1995.

This article was originally published in the March 2019 edition of Wanted in Rome magazine.

General Info

View on Map

80th anniversary of the Battle of Monte Cassino

Montecassino, 03043 Cassino FR, Italia