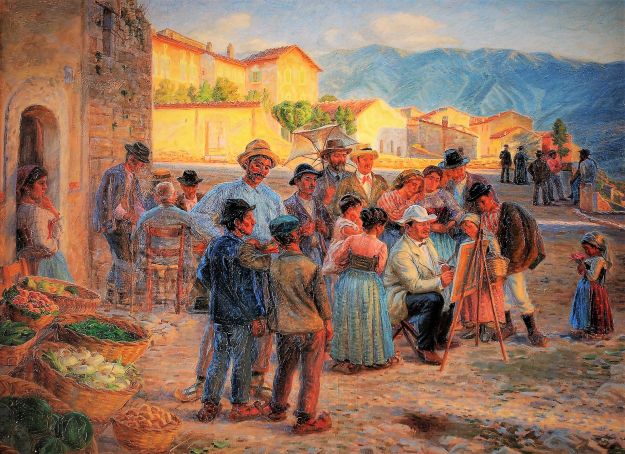

How an idyllic colony of Scandinavian artists in a mountain village in Abruzzo came to a sudden end after 30 years.

Early in the morning of 15 January 1915 the Abruzzo region was hit by an even more terrible earthquake than the one of 6 April 2009. The Marsica earthquake (as it is known) claimed over 30,000 victims and reduced the town of Avezzano and many of the surrounding villages to rubble. It also shattered the 30-year-long dream of a group of Scandinavians who had founded an idyllic artists’ colony in the mountain village of Civita d’Antino.

Civita d’Antino, an ancient walled stronghold perched 904 m on a rock overlooking the wild and beautiful Roveto valley, was “discovered” in 1883 by the Danish artist Kristian Zahrtmann who was captivated by the magnificent scenery, the quality of the light and the warm hospitality he received from the village inhabitants. He set up residence in the Casa Cerroni family inn just inside the Porta Flora gate leading into the town and stayed there for much of his life. Zahrtmann established a summer school for aspiring Scandinavian artists and over the years he was joined by some 80 painters, many of whom were to become famous.

The artists all lodged at the Cerroni inn and had a very jolly time of it, according to the letters many of them wrote home, praising the food, the peasants singing in the fields, the abundance of willing models, the wine and the friendliness of the local people. The Golden Age of this Nordic artists’ haven came to an abrupt end with the disaster of 1915, which virtually destroyed the village.

When the earthquake struck, only one Danish artist was actually in Civita d’Antino. 25-year-old David Hvidt fled to Rome in the clothes he stood up in to try to get help for the stricken community. He met fellow Dane, the writer Johannes Jorgensen, who had rushed from Siena as soon as the news of the catastrophe had reached him, and they set off together on a perilous car journey to the earthquake zone.

Jorgensen published an account of their adventure, describing their hair-raising drive and the tragic scenes they witnessed along the way. Translated into Italian and reprinted in 2005, thanks to the efforts of Antonio Bini, a professor of tourism sociology at the University of Teramo, it makes fascinating reading. Zahrtmann died in 1917 and his school was never revived, although a few of the artists continued to visit in the years after the earthquake.

Civita d’Antino was patched up and rebuilt but, like so many other remote Italian communities, its population shrank as families emigrated to the industrialised north in search of work. Its story was largely forgotten until Bini happened to come across the catalogue of an exhibition held in Copenhagen in 1908 featuring the works of 24 Danish artists in Civita d’Antino.

Intrigued, he began to investigate. The result was a book on the subject entitled L’ Italian Dream di Kristian Zahrtmann. La Scuola dei Pittori Scandinavi a Civita d’Antino. Bini is keen to put the forgotten village back on the map and has organised several promotional events with the Danish Academy in Rome. Although the village was badly damaged, many of the buildings and scenes immortalised by Zahrtmann’s school are still recognisable. The massive old Porta Flora, at the head of a sweeping flight of stone stairs, still stands today, just as when Knud Sinding painted the local women in their colourful costumes drawing water from the adjacent fountain.

The Casa Cerroni inn is still there. Unfortunately, however, it now lies empty and shut. We were unable to see the dining room where the company of artists was immortalised by Peder Severin Kroyer in 1890 and where they amused themselves decorating the walls with invented coats of arms. The local mansion house, Palazzo Ferrante, is also abandoned. It lost its top storey, as well as most of its vast and magnificent park, where long, low tenements were built to house the homeless. A rough footpath through uncultivated fields takes us to the old cemetery, which was in use until 1977.

This is not a burial ground as we usually think of it, but a stone-built roofed corridor with inscriptions on the walls commemorating the dead, who were interred under the floor. Adjoining the building and open to the sky is the narrow grassed strip of deconsecrated ground where non-Roman Catholics were buried.

These included a few of the Scandinavian artists who died there. We can read the memorial plaque dedicated to Anders Trulson, a young Swede who succumbed to tuberculosis in August 1911, just ten weeks after he had arrived. Another tomb is marked only with the artist’s initials and the date of his death – 13 August 1893 – and the inscription: “I was a stranger and you welcomed me.” His wife – also marked by her initials – joined him eight years later.

In Civita d’Antino, Zahrtmann and his artists’ colony are fondly remembered in street and place names. Zahrtmann was made an honorary citizen in his lifetime and a stone inscription at the Porta Flora commemorates his long sojourn in “the months of sun and light.”

By Margaret Stenhouse

How to reach Civita d’Antino: take the A24 Rome-Pescara motorway and exit at Avezzano, then take the superstrada for Sora, exit Civita d’Antino. Where to eat: Locanda di Zahrtmann (also B&B), tel. 329/7075041. Regional home cooking and warm hospitality.

This article was published in the June 2010 edition of Wanted in Rome magazine.

Cover image: Frokost i Sora by P. S. Krøyer

General Info

View on Map

A Danish dream in Abruzzo

67050 Civita D'Antino AQ, Italia