In the mid-70s, the Banda della Magliana arose to become the most powerful criminal organization Rome has seen in centuries.

The city of Rome has always been a complicated city to try and rule. From the unstable world of Italian politics to the Vatican city, one might think that it's impossible for Rome to be controlled by one person or organization.

However, in the mid-70s, a small group of criminals from the suburbs arose to become the most powerful criminal organization the city has seen in centuries. Dubbed the "Banda della Magliana" by the media because several of its members came from the neighborhood of Magliana, the group would rise to rule over the capital of Italy during one of the countries most turbulent periods.

Like any powerful organization, they needed a charismatic leader to show them the way to prominence and a young aspiring criminal from central Rome named Franco Giuseppucci would prove to be just the man necessary to conquer the city.

Franco Giuseppucci

Franco Giuseppucci was born in the Trastevere district in central Rome in 1947. As a teenager, he began working at his father's bakery which earned him the nickname Er Fornaretto "The Little Baker." However, Giuseppucci was forced to leave his job after his father, who had a criminal background, was killed in a shootout with the police.

Giuseppucci was a strong fascist sympathizer and it was through his allegiance to fascism and the propagandist actions of the Italian Social Movement (MSI) that Giuseppucci first met neo-fascists such as Massimo Carminati and Alessandro Alibrandi, as well as other members of the Italian terrorist neo-fascist militant organization Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari (NAR). His connections to the NAR would prove to be vital as they would later be involved in many of the criminal projects of the Banda della Magliana.

After leaving his job as a baker, Giuseppucci found work as a bouncer for a gambling house in the seaside neighborhood of Ostia. This was when Giuseppucci first came into contact with the criminals that were operating in Rome at the time. Despite his neo-fascist views, Giuseppucci found that he had more in common with the criminals that he met in Ostia as he was more focused on money and wealth than the political extremists of the NAR. In those years, the criminal underworld in Rome was disorganized with no one group having control over the whole city. Instead, many small, independent groups known as batterie, usually consisting of about 3-4 members, operated in neighborhoods around the city. These groups dealt mostly with gambling and some robberies.

There was one instance of a group known as the Marsigliesi clan, led by Albert Bergamelli and Laudavino De Sanctis, which gained considerable power and wealth through kidnappings and small-scale drug trafficking in the city. This was however an isolated case in what was a very bland criminal landscape in the city. Rome was considered a land of conquest for other larger, more powerful, and well-established criminal organizations such as Camorra and Cosa Nostra, both of whom had a presence in the city at the time.

It was in 1974 that Giuseppucci joined one of these batterie in the Trullo district. From the very beginning, he was respected for his charisma, organizational skills, and resourcefulness and soon became the leader of the group. This also led to him forming friendly relationships with other members of other batterie groups as he began to make a name for himself in the Roman underworld.

Giuseppucci was also an avid gambler and spent a lot of time at betting shops for horse races. He began to make a regular income by lending the money he had acquired through robberies out on usury at interest rates of 20-25%. It was at one of these betting shops that he met Vincenzo Casillo, lieutenant to the Nuova Camorra Organizzata (NCO) boss Raffaele Cutolo, whose group also had an interest in Roman betting shops.

Giuseppucci lived in a mobile home, which became a common hiding place for members of batterie and his friends in the NAR to store their weapons. However, in 1976 the Carabinieri discovered this hiding place, and Giuseppucci was subsequently thrown in jail but was released after only a few months because a broken window in his caravan managed to convince prosecutors that the weapons had been placed there by others to frame him. This proved to be only a minor setback for him and he simply chose to store the weapons elsewhere while continuing to expand his criminal enterprise into new ventures. He had ambitions to create a gang that would control the entire city of Rome and which did not operate on a traditional "pyramid" structure but rather where every member of the gang was considered equal.

That same year he took part in the kidnapping of jeweler Roberto Giansanti along with several Neapolitan associates of Casillo. Giuseppucci's role in the kidnapping was to study the victim's habits while the Camorristi would carry out the abduction. The operation proved to be far less lucrative than any of them were hoping. Giansanti had to be released after just 52 days because he had fallen sick and the eight kidnappers received 350 million lire as ransom, far less than the 5 billion they had originally demanded.

A chance Encounter

The original core of the Banda della Magliana gang was formed almost by accident. After being released from jail, Giuseppucci was given a stash of weapons by his friend Enrico De Pedis. De Pedis ran a batteria in the neighborhood of Testaccio but was in jail at the time. Known as Renatino, De Pedis’ group worked closely with that of Danilo Abbruciati who ran a batteria in the nearby neighborhood of Trastevere. The two of them were quickly becoming well respected in the Roman underworld. De Pedis was well respected among his associates because of his straight edge, no-nonsense characteristics. He did not drink, did not smoke, always wore designer clothes, and had a strong entrepreneurial sense, which would prove to be very important for the gang later as he would become the key for their connections to the Vatican and some politicians.

Giuseppucci had placed the weapons in the trunk of his car. As he was on the way to hide them, he stopped at a cafe to grab a snack and left the keys of his car on the dashboard. At this moment, another street criminal by the name of Paulo Tegani, unaware of who the car belonged to and what it contained, took advantage of the opportunity and stole the car. Upon discovering the weapons, Tegani decided to sell them and quickly found a buyer in Emilio Castelletti, to who he sold the weapons for two million lire. Giuseppucci immediately went looking for the car and it didn't take long for him to discover that the weapons were now in the hands of Castelletti, who worked for a batteria of another notorious criminal in the Magliana neighborhood: Maurizio Abbatino.

Abbatino, known as Crispino because of his curly hair had been the leader of a larger batteria of about ten members since 1975. Another important criminal in the city, Nicola Selis, known as “Nicola the Sardinian” because he was born in Nuoro, had been leading a batteria that operated between the neighborhoods of Acilia and Ostia. Selis’ group specialized in armed robberies and train robberies. While incarcerated in the Regina Coeli prison with one of his associates, Antonio Mancini, Selis came up with a plan to form a batteria far larger and more powerful than the ones that had existed in the city for years. His idea was to form a gang similar to that of Camorra in Naples, with capillary control over all illicit activities, first and foremost the drug dealing market, and to maintain control by eliminating all other competition.

Upon his release from prison, Selis learned of Giuseppucci’s gang and of their similar ambitions to gain control over Rome. He and Mancini immediately went to join Giuseppucci’s group, strengthening it even further. Therefore, it can be said that Selis was technically Giuseppucci’s precursor to forming the band.

This brings us back to the chance encounter between Giuseppucci, De Pedis, and Abbatino. Rather than fighting and killing each other, they decided to join forces to create a criminal band that would take control of the entire city. Each brought with them members of their groups and continued to slowly recruit more members, becoming steadily larger.

The organization operated under the principle of stecca para, which meant that members would receive equal shares and lived off dividends from the criminal organization. However, the largest percentage of the gains was kept in the casa comune, a common fund used to purchase anything that might benefit the organization, be it weapons, drugs, or even the corruption of state figures.

Should any of the members be imprisoned, money would continue to be sent to them through their families, while successful members had to keep up their criminal activities to remain operai del crimine "crime laborers." Although the group remained decentralized, Giuseppucci became their virtual leader and was the one to propose further expansions and operations.

The Kidnapping of Duke Massimiliano Grazioli Lante della Rovere

In 1977 there were sixty-six kidnappings in Italy, mostly of politicians and wealthy people. This would be the group's first big undertaking together, the kidnapping of Duke Massimiliano Grazioli Lante della Rovere.

The 66-year-old Duke was a Roman nobleman and landowner as well as the husband of Isabella Perrone, part of the family that formerly owned the Roman newspaper "Il Messaggero." However, how could a group that had only recently banded together and had little to no experience in the matter kidnap someone as the duke? The answer was simple, with a mole. Enrico, an acquaintance of Giuseppucci who knew the duke's son through their time spent at the racing and betting rooms was able to provide the gang with plenty of information to kidnap the noble.

The kidnapping took place on Monday the 7th of November, 1977 at around 18:30 in Via del Casale di San Nicola in Settebagni. The duke had been visiting an estate called the Torretta, which had a large pasture with horses that were dear to the duke. The kidnapping was attended by Maurizio Abbatino and Renzo Danesi, who drove the cars that blocked the duke and his entourage, as well as Giuseppucci, Paradisi, Piconi, Castelletti, and Colafigli along with four members of a batteria from the Montespaccato area. Because many of the members were inexperienced with kidnappings, they enlisted the help of the group from Montespaccato to hide the duke in the Campanian countryside. They managed to mislead investigators by moving the duke to different locations, starting in Primavalle before moving to Aurelia and then to the Salerno area.

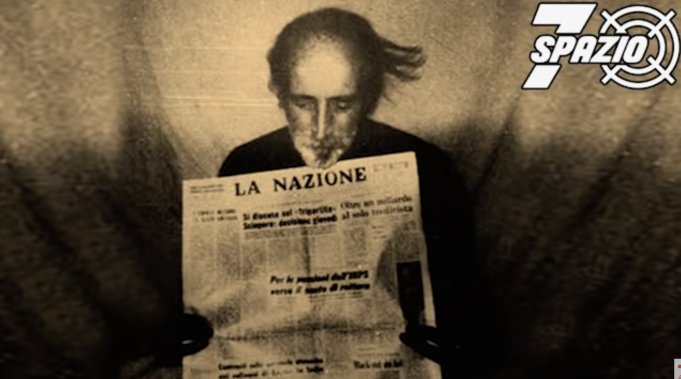

It was Giuseppucci and Abbatino who directed the negotiations between the Banda della Magliana and the Grazioli family as De Pedis was in prison following a robbery. Starting on December 1st, the group addressed five letters to the family asking for ransom, usually accompanied with pictures of the duke to prove to the family that he was alive. They also managed to elude authorities of the duke's location by showing him holding copies of the La Nazione newspaper, suggesting that he was being held in Tuscany.

The gang initially requested 10 billion for ransom, but this was eventually reduced to 1.5 billion. On the 14th of February, 1978 the duke's son delivered the ransom, following a complicated set of instructions to do so. He was forced to find instructions by looking through various waste bins and telephone boxes throughout the city, before being instructed to throw the bag with the ransom from a bridge on the Cassia. Whoever collected the ransom informed the duke's son that he would soon receive a phone call with instructions as to where he could receive his father.

However, the phone call never arrived. While being held captive, the duke had seen one of the members of the Montespaccato group unmasked. This compromised the entire operation and the group decided that they needed to kill the duke to prevent him from identifying any of his captors. Giuseppucci and the Banda della Magliana did not take part in the execution, but they did not oppose it either, as they already had the ransom. The duke was buried somewhere in the Campanian countryside and his body has yet to be discovered.

The ransom was split fifty-fifty with half going to the Banda della Magliana while the other half went to the Montespaccato group. Thirty percent of both sums had to go to the telephone operator and twelve percent was sent to Milan to a member of Francis Turatello’s group for recycling. In total, the kidnapping brought in about 350 million lire each.

Entry Into the Drug Market

Giuseppucci proposed to his friends, to put part of the reward towards a common project by investing in the drug trade. Selis helped Giuseppucci gain the support of the mafia as he was a close associate and godson of Raffaele Cutolo, the boss of NCO. It was around this time that Selis and his group joined with Giuseppucci, and he became the main link between the Banda della Magliana and the NCO. Cutolo met with Giuseppucci and Abbatino. He tested their reliability by commissioning a favor from them, which they satisfied in full, and thus the two went into business together with the NCO supplying drugs for the organization.

At the time, the drug market was on the rise, and controlling it promised to bring in a lot of money for the organization. They decided to divide the city into zones with each zone being controlled by one or more members of the gang. The neighborhood of Testaccio was given to Giuseppucci and Abbruciati; Trastevere and Centocelle were controlled by De Pedis, Raffaele Pernasetti and Fabiola Moretti; the Magliana and Monteverde neighborhoods were headed by Abbatino and partly by Colafigli; Ostia and Acilia under the control of Selis along with contributions from Leccese, Lucioli, Toscano, Mancone and the Carnovale brothers; the Garbatella and Tor Marancia areas by Sicilia and Colafigli and the Portuense-Trullo-Prenestino areas were entrusted to Danesi, Castelletti and Urbani. The first batch of heroin came from two Sicilians and was bought by two Chilean exiles.

One characteristic of each member was their unique nicknames that were based on their physical appearance or their personality. Giuseppucci for example was known as Er Negro because of his dark olive skin complexion; Marcello Colafigli was known as Marcellone for his size and strength; Edoardo Toscano as Lavoratore or “worker” because he made himself available to carry out any work necessary, especially murders; Antonio Mancini went by Accattone because of his love of the Pasolini film of the same name and also because he was the only one who was politically aligned with the left; Gianfranco Urbani, known as La Pantera or “The Panther” for his strength and determination in committing crimes; Fulvio Lucioli as Sorcio because he always managed to gnaw something out of everything; Claudio Sicilia, who was born on the slopes of Vesuvius, was known as Il Vesuviano; and Danilo Abbruciati as Il Camaleonte or “The Chameleon” because it was the name of his first youth band.

Each member who held control over an area of the city for drug trafficking had to use any means necessary to eliminate anyone who opposed their power. Those who decided to side with them were given protection and support while those who continued to oppose them were killed. Physically eliminating their opponents however was seen as a bit of a novelty to the group and before long the once small group from Magliana had absolute control over the criminal underworld of Rome.

Assassination of Franco Nicolini

Thanks to his time spent in Ostia and the betting shops, Giuseppucci knew that controlling the gambling market would also yield large rewards. Therefore, on the night of the 25th of July 1978, Giuseppucci decided to eliminate the real owner of the illegal betting at the racecourse of Tor de Valle, Franco Nicolini, known as Franchino Er Criminale. Giuseppucci and his associates decided that Franchino had grown too powerful and arrogant and felt that it was time to put an end to his reign. Another reason for killing Nicolini came from Selis. During joint detention in the Regina Coeli prison, Franchino had made too much noise about organizing gambling dens in the cells and had even sided with the police during a revolt during which he slapped Selis in front of other inmates.

Shortly after midnight on the night of the 25th, there was an ambush. Nicolini left the racecourse and was headed towards his car when he was surrounded by two cars from which seven people emerged. Two of them, Edoardo Toscano and Giovanni Piconi fired nine shots at Nicolini. Meanwhile, Giuseppucci was inside the racecourse where he received an encrypted message over the loudspeaker that Nicolini had been “parked.”

With Nicolini out of the way, the Banda della Magliana now gained full control over the cities drug and betting market. By 1979, just two years after the Grazioli kidnapping, the members of the group had full control over crime in Rome and became very wealthy. They flaunted their wealth with Rolexes, luxury cars, high-powered motorcycles, and 5-star restaurants. Though some members faced prison time for their activities, they were able to leave and sometimes even escape thanks to bribes and political connections.

The group also demonstrated their strength by being uncompromising towards competitors, those who offended them, and even towards friends who "made a mistake." After Nicolini, Giuseppucci’s group committed another murder: Sergio Carrozzi, a swindler from Ostia, who was killed on August 29th, 1979 by Edoardo Toscano.

Carrozzi's crime towards the gang was that he decided to denounce Selis who was forcing him to pay them protection money. The next to face the consequences of offending the gang would be Hamlet Fabiani who was killed on April 15th, 1980 with four gunshots again from Toscano after he had slapped De Pedis and broke a bottle over the head of Colafigli. Then on the 23rd of February, 1982, it was the turn of opposing drug dealer Claudio "Scimmia" Vannicola who was taking away space from the gang and was also killed by Toscano. Next was an affiliate of the gang, Angelo "Catena" De Angelis. De Angelis was close to Selis but had ambitions to cut off a drug lot and keep part of it for himself. He was killed on the 10th of February 1983 by a unit consisting of Vittorio Carnovale, Roberto Fittirillo, and Abbatino.

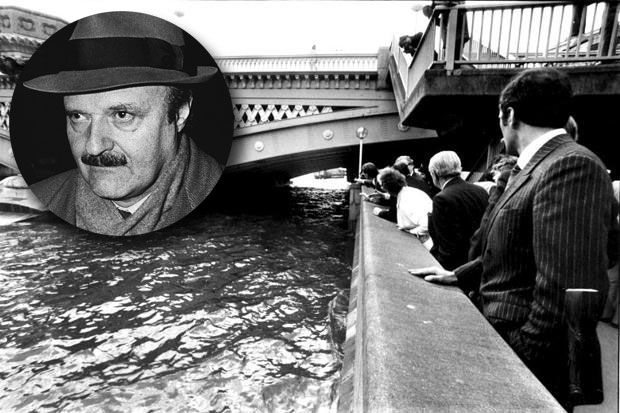

Death of Giuseppucci

On the evening of September 13th, 1980, the gang suffered a sensational loss. Their charismatic leader Giuseppucci, after leaving a meeting with the group near Piazza San Cosimato, was shot in the side by a man on a motorcycle. Giuseppucci was wounded fatally, yet he still managed to put his car in motion and drive to Regina Margherita hospital before he died in the arms of the doctors. His death sent shockwaves through the city as a whole, not just the criminal underworld in which he had inhabited and changed so significantly. He had become a legendary figure in the city, sometimes being referred to as “The Eighth King of Rome.” His murder also rather ironically accomplished his vision of fully unifying the batteria as they were now focused on a common goal of hunting down his killers and avenging his death.

It turned out that he had been killed by two members of the Proietti family, called the Pesciarelli as they had been running a business in the capital's fish markets for generations: in the morning they worked legally, while in the evening attended illegal races, gambling dens and took part in other illegal activities. The killer was Fernando Proietti, while his brother Mario called Palle d'oro drove the motorcycle. The Proietti worked with Franco Nicolini and the death of their leader led them to seek revenge on the Magliana gang. The two wanted to complete the work by going to Tor di Valle to kill Mimmo Zumpano, a friend of Giuseppucci at the racecourse. Zumpano was not found, but they were arrested by two policemen that were in plain clothes.

Another reason why Giuseppucci was targeted by the Proietti family was that he owed one member a debt of 30 million lire, which he had neglected to pay for some time. It didn’t take long for Giuseppucci’s associates to discover who was behind his murder and a hunt for those responsible started immediately. His death sparked Rome’s first major gang war, which ended with the Proietti clan being destroyed after several of their members were killed.

The first member of the Proietti clan to be targeted was Enrico Cane Proietti. Mancini, Colafigli, and Abbatino managed to track him down in Ostia where on the 27th of October, 1980 he was shot in the liver but managed to survive. The Banda della Magliana accomplished their revenge on the 16th of March, 1981. Colafigli and Mancini intercepted Mario and Maurizio Proietti in the Monteverde neighborhood in via di Donna Olimpia 152.

The two brothers were at home and accompanied by their wives and children. Upon discovering them, the Maglianese fired immediately and Maurizio fell to the ground dead, but Mario managed to escape. It wasn't just the families of the two Proietti who panicked, but all the occupants on the street and it wasn't long before the police arrived at the scene. Upon hearing the sirens approaching, Colafigli and Mancini sparked a firefight and took refuge inside another family's apartment, but both of them were arrested. Mancini was sentenced to 28 years in prison while Colafigli was deemed mentally ill and therefore was able to avoid prison time. Colafigli had managed to trick prosecutors into thinking that he had carried out the attack after having a dream where a cat with the likeness of Giuseppucci had instructed him to kill the Proietti. Thanks to the intervention and connections of De Pedis, Mancini was able to have his sentence reduced and moved prisons several times. The war against the Proietti ended on the 30th of June, 1982 when Edoardo Toscano and Roberto Fittirillo killed Fernando Proietti. Mario Proietti meanwhile managed to escape two attempts on his life.

Even though Giuseppucci's original vision for the Banda della Magliana was to create a group with no bosses, his death left the group without a real leader. Nicolino Selis saw this as his opportunity to lead the gang. At the end of 1980, Selis was in prison and was making a lot of noise about his ambitions of leading the gang as he was close to Cutolo. Then, in early 1981, Selis received a 3kg shipment of cocaine from the Sicilians but decided to share it unequally, taking 2 kilos instead of 1.5. Toscano, after hearing about what Selis was doing, could no longer bear it and decided he needed to be killed.

Toscano decided to call a meeting with the other associates. The meeting took place on the 3rd of February, 1981 in front of the Fiera di Roma and was attended by Colafigli, De Pedis, Mancini, Abbruciati, Abbatino, and Pernasetti. Selis did not attend the meeting as he wanted to talk to Mancone, who had stayed home. After the meeting, Toscano and Abbatino went to Mancone's house where they shot and killed Selis. It is said that Selis's body was thrown in a hole on the edge of the Tiber and covered with caustic acid to promote faster decomposition. His body has never been found.

Even though Selis had been a close associate with the Camorra, the Neapolitan mafia decided not to avenge his death to avoid a war with the Banda della Magliana and risk retaliation in the future.

Roberto Calvi’s case

Roberto Calvi, also known as Il banchiere di Dio (“God’s banker”) was in charge of Banco Ambrosiano whose main shareholder was the Vatican Bank. Calvi was killed in London on the 18th of June 1982. Banco Ambrosiano crashed in one of the major financial scandals in the 1980s after it was revealed that it was involved in money-laundering activities with the Mafia as well as funneling funds to the Polish Solidarity trade union (Solidarnosc) and the Contras in Nicaragua.

Those implicated in Clavi’s murder include Giuseppe Calò, a member of the Sicilian Mafia also known as cassieri di Cosa Nostra or “banker of the mafia” as he was heavily involved in the financial side of the mafia’s business and was a member of their ruling inner circle known as the Commission. Flavio Carboni, a Sardinian businessman with wide-ranging interests, Francesco Di Carlo, a former Mafia member turned informant, and Ernesto Diotallevi, one of the leaders of the Banda della Magliana at the time were the others to be arrested in connection to Calvi’s murder.

Visiting the Vatican Museums: All You Need to Know

Just over a year before his death, on the 17th of March 1981, the list of affiliates of the Propaganda Due (P2) Masonic lodge was found. Calvi was a member (card number 519) but his former associates abandoned him to his fate. He was arrested in May of 1981 and was sentenced to four years in prison. However, while out on appeal, he managed to flee to London using false documents which were allegedly given to him by Diotallevi.

On the 19th of July, 2005, Licio Gelli, the grandmaster of P2, was formally indicted by magistrates in Rome for the murder of Calvi along with Calo, Diotavelli, Carboni, and Carboni's Austrian ex-girlfriend, Manuela Kleinszig. Gelli was accused of having provoked Calvi's death to punish him for embezzling money from Banco Ambrosiano that was owed to him and the Mafia. The Mafia was also claimed to have wanted to prevent Calvi from revealing that Banco Ambrosiano had been used for money laundering.

The trial began for the five individuals charged with Calvi's murder in Rome on the 5th of October 2005. Also among the defendants were Calvi's former driver and bodyguard Silvano Vittor. The trial took place in a specially fortified courtroom at the Rebibbia prison in Rome and was expected to last up to two years.

Then, on the 6th of June, 2007, all five individuals were cleared by the court for murdering Calvi. Though the court did rule that Calvi's death was murder and not suicide, the presiding judge of the case, Mario Lucio d'Andria, threw out the charges citing "insufficient evidence" after hearing 20 months of evidence. The verdict was seen as a surprise by some observers. The defense had suggested that there were plenty of people with motivation for murdering Calvi as he was such a high-profile figure with connections from the Vatican to the Mafia who would want to ensure his silence. Also, prosecutors found it hard to present a convincing case as 25 years had passed since Calvi's death. Another key factor was that some important witnesses were unwilling to testify, untraceable, or dead.

The acquittal of Calo, Diotavelli, and Carboni was confirmed by the Court of Appeals on the 7th of May, 2010. After the verdict, public prosecutor Luca Tescaroli commented that for the family "Calvi has been murdered a second time."

The son of Roberto Calvi has claimed that Emanuela Orlandi’s case was closely related to Calvi’s case.

Emanuela Orlandi

On the 22nd of June, 1983, Emanuela Orlandi, a citizen of Vatican City aged just fifteen mysteriously disappeared. The case remains unsolved and Orlandi is still missing. However, some have tried to exchange her for Grey Wolves member Mehmet Ali Agca, who shot the Pope in 1981. Allegedly, some of the members who tried to strike the deal with the Vatican were members of the Banda della Magliana.

In 2005, an anonymous phone call broadcast by the Rai 3 TV live program Chi l'ha Visto? “Who has seen it?”, a transmission about missing people's finding, stated that to find a resolution on the Orlandi case, it would have to be discovered as to who is buried in Saint Apollinare church, and about the favor that Enrico De Pedis made to Cardinal Ugo Poletti at the time.

The Saint Apollinare church is located near Piazza Navona, was home to De Pedis’ tomb until 2012. It is also home to a crypt where Popes, Cardinals, and Christian martyrs are buried. The church is also part of the same building as the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music that Orlandi attended, and is where she was last seen.

In February of 2006, one of the voices behind the anonymous phone call was recognized as Mario, an ex-member of the Banda della Magliana and one of the killers who worked for De Pedis.

The mid-80s and the deaths of Toscano and De Pedis

In 1986, the Banda della Magliana suffered a massive internal blow: Claudio Sicilia turned into an informant for the authorities. Sicilia had survived two attempts on his life and was then arrested for dealing and possession of weapons. This latest arrest led him to repent on October 16th, 1986. With his admissions, the investigators discovered the links between the Gang and the neo-fascists, the international drug trafficking, the Camorra, and relations with institutions and power, as well as ten murders.

From his interrogation, 91 warrants for arrest were issued for as many affiliated with the gang in February of 1987. However, just one month later over half of those arrested were free as Sicilia’s words were deemed unreliable. He later tried to commit suicide in prison, before obtaining house arrest in December of 1990 and was released the following summer. He then moved to the neighborhood of Tor Marancia. Then, on the 18th of November 1991, after turning on his former associates, Sicilia was killed in an ambush in the neighborhood he once ruled over by two men on a motorcycle. The killers had their faces covered and remain unpunished to this day.

The two year period of 1989-90 also saw two murders within the Magliana gang: Enrico De Pedis and Edoardo Toscano. As a result of all the tensions, conflicts, and jealousies within the gang, a war had broken out between the Maglianesi and the Testaccini headed by Toscano and De Pedis. The feud between them effectively ended the dream of the Banda della Magliana to conquer all of Rome. The Maglianese were jealous of the fact that the testaccini had control over prostitution, dealing, usury and robbery, while the testaccini had ties to P2, secret services, and high-ranking figures in politics and finance. Toscano and De Pedis, once friends, now went to war with each other.

The Maglianesi made one last attempt to try and reorganize the gang, but the testaccini, now led solely by De Pedis, were not interested. De Pedis had effectively broken all contact with the gang and Toscano and Colafigli decided that he had to die. However, De Pedis learned of Toscano’s intentions and decided to act first. On the morning of the 16th of March, 1989, De Pedis set up an ambush for Toscano in Ostia using a collaborator from within the gang. The ambush worked and Toscano was killed by Angelo Cassini and Libero Angelico.

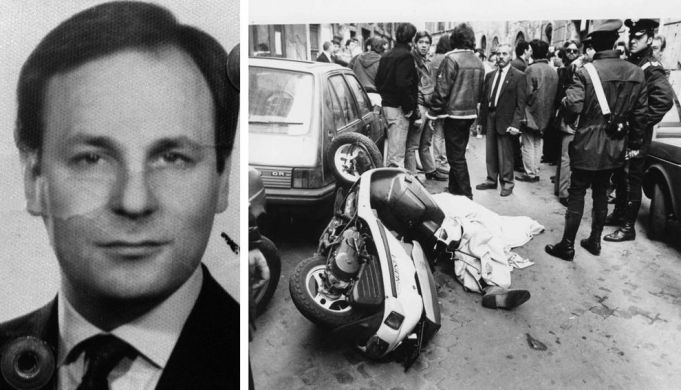

Not long after, Colafigli set up a similar trap for De Pedis. On the 2nd of February, 1990, Colafigli set up a meeting with De Pedis via del Pellegrino near Campo de Fiori using Angelo Angelotti, an affiliate of the gang, as a go-between. Colafigli decided that the two killers should not be associates of the gang as if they were De Pedis would recognize them and run away. De Pedis and Colafigli met and at one point Angelotti made a strange gesture, like telling someone that the person in front of him was the target to hit.

Once the two parted, De Pedis got on his scooter and was joined by two men on a motorbike. The one sitting fired two shots at De Pedis who managed to flee despite his injuries. However, after about a hundred meters, he fell and died a few moments later. De Pedís' killer was Dante del Santo nicknamed Cinghiale and the driver of the motorbike was Alessio Gozzani, both were from Massa Carrara in Tuscany.

The details surrounding De Pedis’ tomb are rather bizarre. De Pedis' funeral took place in the church of San Lorenzo in Lucina (near Piazza Colonna) and his body was buried in the Verano cemetery, although in 1988 when he married he told his wife Carla that he wanted to be buried in a particular church, that of Sant'Apollinare.

However, at the time this seemed impossible as the only people who were permitted to be buried in the church were Roman Pontiffs, Cardinals, and Diocesan bishops. De Pedis would be buried in the church, however, and it was all thanks to a connection he made while in prison. Pietro Vergari, rector of the basilica of Sant'Apollinare met De Pedis while he was in prison and reported that he was a benefactor of the church.

The story of the burial of de Pedis in the basilica of Sant'Apollinare has been a mystery for years: there was talk of a favor done by the De Pedis to Ugo Poletti, the President of the Italian Episcopal Conference (CEI). The "favor" was assumed to be the intervention between the mafia and the Vatican on the return of the money that Cosa Nostra had invested in the Banco Ambrosiano through Roberto Calvi. This money went through the IOR and was never returned because it ended up in the coffers of the Polish union "Solidarnosc". It was discovered that on March 6, 1990, Vergani wrote to Poletti to have the authorization to bring the body of the "benefactor" De Pedis, and four days later, the then President of the CEI agreed. On April 24, 1990, the mortal remains of de Pedis entered the church.

No one knew anything about De Pedis' burial until 2010 when the interview book "Criminal Secret" by Raffaella Notariale and Sabrina Minardi was published. Then, an anonymous phone call was made to the editorial staff of the TV show "Who Has Seen It" about the disappearance of Emanuela Orlandi and how it was related to De Pedis and the Banda della Magliana. De Pedis' remains would be removed from the church in 2012, after which they were cremated and the ashes were thrown into the sea.

Far-right ties and Mino Pecorelli's assassination

As mentioned earlier, many members of the Banda della Magliana, including their founder Giuseppucci, were far-right sympathizers. Though crime, not politics, was their main interest, they needed some help from political extremists.

One of the gang's first contacts with neofascists came in the summer of 1978, just a few months after the assassination of former Italian Prime Minister Aldo Moro. They met criminologist, psychiatrist, and neofascist professor Aldo Semerari at his villa in the town of Rieti. Semerari proposed that in exchange for financing his political activities, he would provide psychiatric expertise to help arrested gang members get released. With the help of Semerari, several gang members were able to effectively avoid any jail time by being declared "completely unsound of mind."

The deal did not last long however as Semerari was assassinated on the 1st of April 1982 in Ottaviano in Naples. Semerari had made the same deal with Cutolo’s NCO as well as with the rival organization of Cutolo, the Nuova Famiglia headed by Carmine Alfieri. In addition to his ties to the mafia and being a famous far-right criminologist Semerari was also a member of the P2 Masonic lodge and had ties to the Italian military intelligence agency SISMI.

Another important far-right link for the Banda della Magliana was with the Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari (NAR) far-right terrorist group. Their connection was largely through NAR member Massimo Carmati, who was a regular customer at Giuseppucci and Abbatino's bar. Carmati quickly became a friend of the gang and he introduced them to Valerio Fioravanti and Francesca Mambro, both of whom were accused of complicity in the 1980 Bologna massacre, in which 85 people were killed and over 200 were wounded. The Banda della Magliana and the NAR became closely linked with each helping the other with their activities. The Magliana gang laundered the money obtained from the NAR's hold-ups to finance their political activities and the NAR helped the gang with various street activities. The most mysterious joint venture between the two groups however came when ammunition, guns, and bombs belonging to both groups were found in the basements of the Italian Health Ministry.

Along with the weapons and ammunition found in the basements were ammunition cartridges of the brand Javelot, a brand that was not easy to find on the market. This find was also significant as four bullets of the same brand were found at the site where Italian journalist Carmine Pecorelli was assassinated in 1979. Pecorelli had published allegations about Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti’s ties to the mafia. Both Andreotti and his leading assistant, Claudio Vitalone, a judge and a politician, have been suspected in this assassination. Andreotti was convicted of ordering the murder of Pecorelli in November of 2002 and was sentenced to twenty-four years in prison. However, the eighty-three-year-old Andreotti was immediately released pending an appeal. Then, on the 30th of October 2003, an appeals court overturned the conviction and acquitted Andreotti of the original murder charge.

During the trial of Andreotti, the Italian justice proved the involvement of the Banda della Magliana in Pecorelli's murder, though, Massimo Carmati, the person materially responsible for the killing, was released. According to the judges, clear links were found between Vitalone and the Banda della Magliana through De Pedis were found. Vitalone was released however due to insufficient evidence.

Influence on Politics

The time in which Giuseppucci and the Banda della Magliana rose to power was a period in Italian history known as the Years of Lead, as it was marked by political instability and violence.

The gang's power and influence, especially Giuseppucci's was not just recognized in the underworld as he had made friends in fields such as cinema and music and was eventually approached by the state itself.

When Aldo Moro was kidnapped on the 16th of March 1978, Italian authorities immediately began seeking where he was being held and asked for help from several criminal organizations including Cosa Nostra, the Camorra, the 'Ndrangheta, and the Banda della Magliana. Giuseppucci was summoned for a meeting with one of Moro's fellow party members, DC politician Flaminio Piccoli, in the outskirts of Rome.

Piccoli wanted to enlist the gang's help as they had extensive knowledge of the city's criminal underworld. In return, the Banda della Magliana would receive adjustments on any trials that involved their crimes. Giuseppucci was able to locate the location of Moro's prison with the help of Selis. However, when he delivered the news, he found that those who wanted to help Moro were no longer interested in his rescue. Moro's body would be found on the 9th of May 1978 in the trunk of a car in central Rome.

Present Day

After Giuseppucci's murder in 1980, the Banda della Magliana entered into a period of decline which they have not emerged from since. After the trials that occurred in the 90s that devastated the gang as much as any war in the past, the Banda della Magliana seemed to be just a memory. However, even though they may not have the same power and influence as they once did, the gang continues to stay active in the capital, with small instances of their activities arising now and again to serve as a reminder that they are still around.

More recently was the discovery and confiscation of the treasures of former Sicilian boss Salvatore Nicitra and 38 of his associates in February of 2020. The "King of Northern Rome" was exposed as being part of a jackpot operation involving usury and extortion linked to slot machine businesses. Nicitra's confiscated assets are estimated to be worth around 13 million euros. This includes his villa in via della Giustiniana with an estimated value of approximately 1.7 million euros. The villa, which includes a swimming pool, a large garden, and marble statues, is just as extravagant as any that the earlier members owned back when they ruled Rome and serves as a reminder that the gang is still alive in the capital.