Art and Science in the Rome of Urban VIII

Rome exhibition retraces a marvellous decade in the 17th century.

The first half of Urban VIII’s long papacy (1623-44) saw science and the arts proceed intertwined, the one complementing the other as perhaps never before.

The new pope enthusiastically supported both, while new institutions like the Academy of the Lincei numbered astronomists (Galileo), naturalists (Federico Cesi), mathematicians and master painters (Pietro da Cortona) among its members.

Two Cultures

This happy symbiosis of ‘the Two Cultures’, as they had come to be called, is celebrated in a fascinating exhibition at Palazzo Barberini: celestial and terrestrial globes, sundials, nocturnal clocks, telescopes, busts, architectural designs (Borromini’s), prints and paintings have been arranged to stretch the annus mirabilis of Urban’s accession to a decade. Until, of course, Galileo’s trial (1633) and the Inquisition intervened.

Galileo

But back to 1623 and Galileo’s Il Saggiatore / The Assayer. Room 2 features the work’s giant frontispiece; one might playfully guess magnified a dozen times to invoke the power of Galileo’s telescope compared to Hans Lipperhey’s Dutch prototype. Galileo’s membership of the Lincei Academy and the book’s dedication to the new pope are eminently legible.

Back in 1612, in S. Maria Maggiore’s Pauline Chapel, Galileo’s friend, Ludovico Cigoli had used the same instrument to depict Santa Maria standing on a moon pocked with craters and behind her a sun marred with spots, both casting doubt on the Ptolemaic/Aristotelian system whereby all planets are deemed to be perfect spheres.

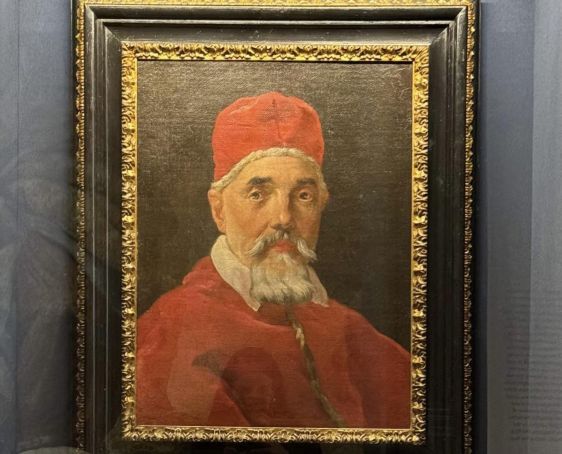

Few had objected then. Nor in 1623 did the new Barberini pope, here represented by Gaspari Mola’s bust and a portrait by Bernini, object to Galileo’s book outlining the basis of his scientific method, the primacy of mathematics, the importance of observation over theory. Peaceful and enthusiastic dialogue seemed to be the order of the day. Galileo was invited to Rome six times to enlighten the pope, a keen sky-skywatcher himself, on his new findings.

Also, changing scale, to discuss perhaps what was now visible under the microscope. Thus Galileo states, on offering his fellow Licean Federico Cisi a version of the same instrument, his satisfaction of studying first a flea, and then “his huge satisfaction in seeing how flies walk in mirrors.” Fleas, flies (the horsefly or tafano was originally the Barberini’s family emblem), and, in a marketing make-over, real and/or heraldic bees. They are all over Rome, on the fountain at the corner of Pizza Barberini, on the sides of the building coming in.

Here they feature in microscopic magnificence in a print from 1624 from Galileo’s fellow academician Frasco Stelluti’s Melissografia. Art and the new optics reconverge. To quote a text of the time, “Bees possess the truth of many realms, of science above all mathematics. They are expert in geometry, circles, squares and angles. No surveyor with all his instruments could better compass their cities about.” One might say, just like Borromini, another Barberini artist and whose architectural designs are here displayed.

Annus Mirabilis

Enough, one might think, for a single emblem. Except now another key figure enters the Barberini iconography, Tommaso Campanella, priest, scientist, poet, anti-Aristotelian and long-time convict. His embattled face portrayed here is by Francesco Cozza. Published in the same Annus Mirabilis (1623) was Campanella’s Utopian City of the Sun.

Urban, had little difficulty, perhaps, in co-opting the Sun an image for himself. He, “the Christian Apollo”, would likewise “fertilize the earth every sunrise to nourish the bees indefatigable labour” while “fuelling the intellect with the nectar of art and science.”

From bees to stars

Meanwhile, moving from bees to stars, it was at the same pope’s behest that Campanella was freed from prison. The ex-heretic was also, luckily for him, an astrologer.

Once appointed to Urban’s court, he was able to realign Urban’s horoscope after a hostile Spanish faction, via two eclipses in 1628 and 1638, had predicted the French-backed Pope’s premature death. As D.P. Walker’s Spiritual and Demonic Magic describes it, two men would seal themselves off in a special room, performing rather dubious astrological rituals, using two candles and five torches to represent the planets. Needless to say, the pope escaped the fate predicted, his papacy being one of history’s longest.

From science or pseudo-science to art: the astral conjunction on the day of his accession (5-6 August 1623) is seen (as realigned with Campanella’s help?) in the 11 female figures/constellations surrounding Sapienza in Andrea Sacchi’s 1629-31 ceiling fresco Allegory of Divine Wisdom.

Barberini bees

Next, from the sun to sundials. In another room pride of place goes to a facsimile of Borromini’s sundial as designed by mathematician and friend of Tycho Brahe, Teodosio Rossi. (The original structure remains in its garden on the Quirinale. The Barberini bees perched on top have since departed, along with other parts, dismantled maybe after Urban’s death and hinting that the Barberini pope was not without opponents.) In this replica the same bees have been restored.

Elongated by shadow, the tail of each points the hours across four faces of the same concave shape that would become such a hallmark of Borromini’s architecture (cf. his San Carlino church up the road) So yet again bees, “Custodians of the doors and observers of the heavens” the original’s base cites Virgil’s Georgics (vv. 164-165), and a good omen for the papacy to come.

Copernican vision

A pity that in 1633, for science anyway, everything would change. Galileo had believed from his meetings with the pope that, regarding the Copernican vision, there was a new tolerance. Thus he went on to write The Dialogue concerning the Two Chief World Systems, using Italian to increase its readership. The giant frontispiece is displayed here. The problem is the third figure on the right – Semplicius, a diehard Aristotelian into whose mouth Galileo puts a series of whose views that appear simple to downright foolish.

Worse, they carry a striking similarity to the pope’s. Urban, till then noted for his tolerance on astronomical matters, reacted with explosive rage, seeing in Galileo’s sarcasm a friendship betrayed. This was no time, the Pope must have reasoned, to seem weak. All the more so now, on another front, the Catholic armies fighting in the Thirty Years War in the north were on the defensive.

Had Galileo been gifted, like that other papal protégé Bernini, with a sense of diplomacy, could history have turned out differently? Only too ready to accept the sun’s centrality as a metaphor for himself, might the ‘Christian Apollo’ (to use Campanella’s moniker) have come round to accepting the same heavenly body’s centrality as a Copernican fact?

To think how in 1620 Pope Urban (then Cardinal Maffeo Barberini) had written a poem – Adulatio Perniciosa – in Galileo’s praise: “When the moon shines forth in the heaven/ and sprinkles its glittering fires/ in a serene arc….they were discovered by your glass, Galileo.” As things happened, Galileo’s book was only taken off the Papal index in 1835; Galileo spent his last eight and half years in confinement. Art and/or here versus science as in a possible exhibition subtitle. Plus, yes, raw emotion.

The last room is something of an addendum. If under Urban VIII astronomy, at least from 1633, stepped backward as the pope ‘lapsed’ into the Aristotelian/Ptolemeic rigidity of his predecessors, under the succeeding Innocent X science, in the form of optics, continued to astound. As here in two works of ‘anamorphic dioptics’: first is a curiously painted plank laid flat. Courtesy of a cylindrical mirror on top watch Louis XIII, the French king, metamorphose from an amorphic if bright-coloured pancake into his true likeness.

On a grander scale the room’s back-wall reproduces in its entirety the 1646 mural in Santissima Trinità dei Monti’s cloister. At first sight it seems a curious if inconclusive representation of some geological strata, a sort of wasteland with some branches and a river thrown in. Until you look left. Take care not to bump into it. That museum doorway is a strategically-placed mirror from which emerges the miraculous figure of Calabrian hermit/saint Francesco di Paola absorbed in prayer.

To cite one of the attendants about the exhibition as a whole, “saloni pochi, ma bella ricca.” For those with an hour or so to spare, an exact recommendation indeed.

Martin Bennett

The exhibition La Città del Sole. Arte barocca e pensiero scientifico nella Roma di Urbano VIII can be seen at Palazzo Barberini, Via delle Quattro Fontane 13, until 11 February 2024. For more details see website.

General Info

View on Map

Art and Science in the Rome of Urban VIII

Via delle Quattro Fontane, 13, 00184 Roma RM, Italy