An exhibition at the Capitoline Museums reflects on the turbulent decline of the Roman empire.

“C’è la crisi” is a present-day refrain often heard in Rome. Following on from the more positively-titled Age of Conquest and Age of Balance, the Capitoline Museums' latest exhibition Age of Anguish offers a timely antidote and reminder that things could be significantly worse. Think plague, coups d’état on a yearly if not monthly basis. Then add “imperial overstretch” as the Sassanids in the east grew stronger, eventually taking hapless Emperor Valerian captive.

At the same time, dramatically falling population levels back in Italy led to a reliance on foreign auxiliaries, while the financing of the top-heavy army led to rampant inflation and rising taxes. These were just a few of the ills which third century AD Romans had to put up with. Hence the title, inspired by the W. H. Auden poem Age of Anxiety from the 1940s. One might be excused for seeing that emotion on the splendid but crinkle-faced lion at the exhibition entrance (actually the lion is meant to symbolise the triumph of life over death). Less ambiguous are the faces on some of the busts.

With an average one-year life-span for each emperor, it is not surprising that the faces of the barracks emperors looked wrinkled and vexed. More reassuringly, the first bust in the Protagonists section is of Marcus Aurelius (161-180 AD), the same to be seen dispensing clemency to a Barbarian in the frieze as one climbs the stairs to the exhibition entrance. Yet even Marcus Aurelius’s legions suffered plague. Across from him primps Commodus, villain emperor from the Gladiator film and philosopher’s son gone wrong, bedecked as Hercules, complete with club and lion-skin headgear, two giant paws for clamps. Flanking him, two Tritons sport seaweed. Along with the Esquiline Venus, the group came to light in 1874 during excavations under Piazza Vittorio, the one-time Horti Lamiani. Such self-glorification did not prevent Commodus from being dispatched in a plot hatched by his concubine Marcia. Pertinax then found himself catapulted to power, only to be speared to death by the Praetorian Guard 87 days later; his austerity plan, however necessary, having proved less than popular.

Didius Julianus then bought his way to power, lasted for three months, and was deposed and killed by military strongman Septimus Severus (193-211), who set about restoring order. Spin-doctoring being nothing new, he is on display in various guises, his hairdos (like those of his son Caracalla) modelled after Marcus Aurelius’s to give the stamp of legitimacy. One of the three busts of Severus on display is of translucent alabaster fashioned during the emperor’s journey to Egypt in 199 AD (statues often substituted the emperor’s person at public ceremonies). Caracalla’s murdered younger brother Geta also puts in an appearance, as does infamous and sun-worshipping Heliogabalus, whose imperial excesses included marrying a vestal virgin, suffocating dinner guests with rose petals, and, the grossest pleasure of all, prostituting himself in the royal palace.

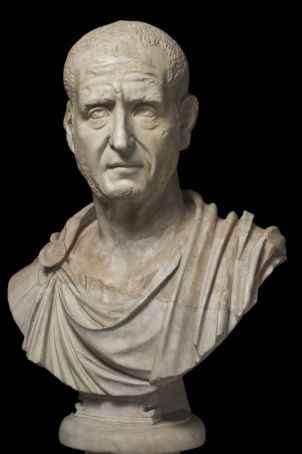

The Severan dynasty – Rome’s last – ended with the army’s election of Thracian giant and ex-wrestler Maximinus Thrax (235-238). The 18th-century English historian Edward Gibbon devotes a whole chapter in his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire to his wickedness, partly evident on the bust here: first of the “barracks” emperors. After him, “no emperor could think himself safe upon the throne, and every barbarian peasant of the frontier might aspire to that august, but dangerous station.”

Other barracks emperors follow like skittles. The empire's golden age had turned to rusty iron. No more godlike or philosophic poses but, as in the bust of Philip the Arab (244-249), short hair and rough-and-ready stubble, or in the case of Trajan Decius (249-251) a “tired and distressed” look, to cite the catalogue. Maybe he had foreseen his death at the hands of his once trusted general Trebonian Gallus (251-253), he of the massive bronze body and disproportionately small head appearing in the exhibition courtesy of New York’s Metropolitan Museum.

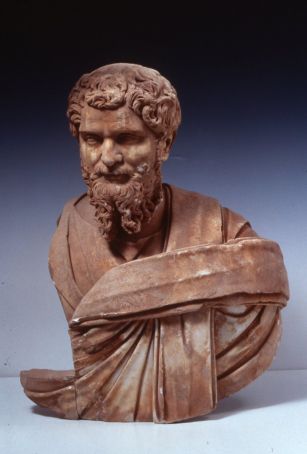

Opposite Decius a male civilian “with a rightward twist of the eyes” portrays “the pain of living though such times” while a row of arm-chaired philosophers from Dion, in Macedonia, sit in inscrutable silence.

Some stability is resumed with the Tetrarchy, when Emperor Diocletian (284-305) decided that the rule of the empire had become too unwieldy for one man and therefore divided it into four; two emperors (or Augustae) – himself and his general Maximinian – and two Caesars, Galerius and Constantinius Clorus.

Adding to the new sense of stability was a series of reforms, the subject of Room III in the exhibition, entitled Learning from the Crisis. Albeit this comes with the proviso that things were so far gone that, to quote Gibbon, “internal weakness invites calamities for which the remedies are themselves harmful.”

This symmetrical version of power-sharing was introduced, here represented by casts of the famous statues embedded in Venice’s S. Marco cathedral. Bearded Augustus and un-bearded Caesar embrace twice over, eagle-hilted swords for now safely in their sheaths. “Their principal distinction was the imperial or military robe of purple, and …a style of government closer to Persian absolutism,” wrote Gibbon. Significantly, the statues are the same colour, their porphyry coming from the eastern Egyptian desert and probably carved in the same province before being transported to Constantinople.

Rome has already become sidelined from its own empire. Within just one generation the Tetrarchy would dissolve into civil war, Constantine, son of the Tetrarch Constantius Clorus (see the trademark hooked nose) emerging victorious over Maxentius, son of another Tetrarch, Maximinian, before the empire’s capital shifted definitively to Constantinople in the east.

If the busts of the emperors tend toward uniformity, the room entitled Religion is as varied as one can get. Death being rife, strange cults from the east became more popular as the traditional public gods lost ground. (As meat prices sky-rocketed, sacrifices to the old gods diminished.) From Egypt came Bellona, Isis, Osiris and Apis, all on display here. One sarcophagus features a marine parade and another, of a dead soldier, is carved with a mounted knight fending off a throng of marble lions.

From Thrace came the weird cult of Sazios, physical contact with the god simulated with the use of sacred snakes and lizards, represented here by a tiny hand with animal growths seeming to emanate out of it.

From Persia came the cult of Mithras. One of the sculptures, with the god’s original gold and red coating still intact, is a reminder that most marble statuary to an ancient Roman would have appeared multi-coloured. Riding a chariot, Mithras kills a bull, with a snake sucking the animal’s blood and a scorpion clutching its genitals. Rather more decorously, Cautes, bearer of light, with a raised torch and rooster, announces daylight on the left; off right, Cautopates, genius of the dark, accompanied by an owl, turns his own torch upside-down.

In the quest for resurrection and personal (rather than public) salvation, none of these cults would be able to compete with Christianity, Christ here being depicted as raising Lazarus, in others as the Good Shepherd, an iconic archetype actually going back to ancient Greece.

A graffito of a donkey-headed crucifix might point the way forward to persecution of the Christians under Diocletian, but the massive head and raised right hand of Constantine, the first emperor to recognise Christianity, dominates this space of the exhibition.

However, easy to overlook, the exhibition’s arguably most impressive piece of statuary lies at the back of the last room: the 230 AD sarcophagus carved with larger-than-life Cupids.

An earlier section featuring military funeral monuments, which were becoming more and more common as, with ever increasing militarisation, soldiers climbed the social ladder, has another sarcophagus featuring the deceased on horseback fending off a throng of marble lions. Both works prove that what the geniuses of the Renaissance could achieve, the Romans had done previously, crisis notwithstanding.

Martin Bennett

The Età dell'Angoscia exhibition runs until 4 October at the Capitoline Museums, Piazza del Campidoglio, tel. 060608.

This article appeared in the May 2015 edition of Wanted in Rome magazine.