Rome exhibition reflects the colour and tragedy of Kahlo's life and art

Frida Kahlo, the world's best known exponent of Latin American art, had her first major exhibition in her native Mexico City in April 1953. By that time her health had deteriorated to such an extent that her doctors forbade her from attending the opening night. However, moments after hundreds of people had poured into Mexico's Gallery of Contemporary Art, an ambulance and a motorcycle escort pulled up outside. The astonished crowd witnessed a gaunt Kahlo being stretchered into the gallery to her four-poster bed, which had been installed earlier that day.

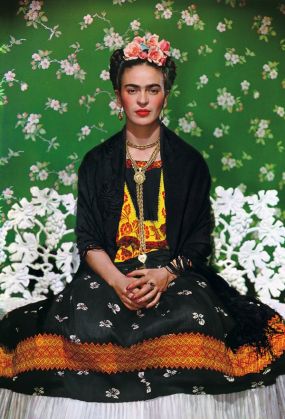

The heroic spectacle generated such shock and reverence that most of the assembled press photographers abandoned their cameras, failing to record the extraordinary event. Fortunately one photograph does exist. It shows a weak and wide-eyed Kahlo, dressed in traditional Mexican costume and jewellery, staring up at her supporters. Kahlo's bed was decorated with photographs of her husband, the revolutionary muralist Diego Rivera, her political heroes such as Josef Stalin, her family and friends, while attached to the bed's canopy hung grinning papier mâché skeletons. One by one, Kahlo's friends and admirers queued to greet her personally. Later, led by Rivera, they formed a circle around her bed, drinking wine and singing Mexican ballads with her until the early hours. Within a year she was dead, aged 47.

On the 60th anniversary of Kahlo's death, Rome's Scuderie del Quirinale hosts a remarkable retrospective in her honour. Curated by Helga Prignitz-Poda, this beautifully presented exhibition explores Kahlo's art and her links with the most important cultural movements of her time, from Stridentism to Surrealism to Magical Realism. The exhibition comprises some of Kahlo's most celebrated paintings and spans the full spectrum of her artistic career.

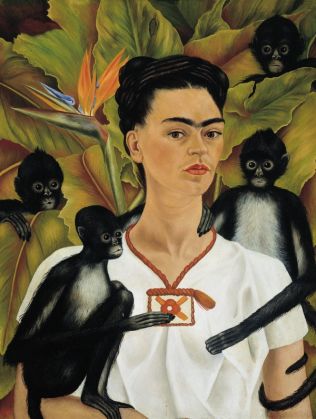

Her 110 works on display feature more than 40 of her portraits and self-portraits, of which she said: “I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best.” Pride of place is reserved for her Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, never before exhibited in Italy.

Like a child arriving at a beach for the first time, it is tempting to race through the Scuderie's halls to consume Kahlo's exotic world all at once. Her unsmiling self-portraits observe the viewer who is bombarded by her colourful and arresting imagery, the fruit of a vivid imagination and a skilled hand.

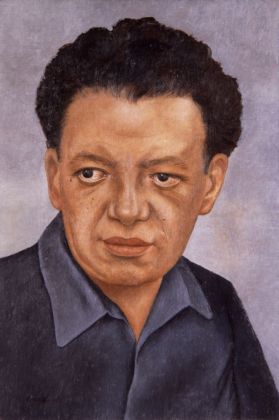

Unlike many so-called major exhibitions, this one does not rely on supplementing the central artist's work with pieces by other lesser-known contemporaries. The inclusion of a small number of artists associated with Kahlo is perfectly within context and adds to the overall vitality of the exhibition. Chief among those sharing Kahlo's wall space is her husband Rivera whose exhibited works include Portrait of Natasha Gelman and a sensuous lithograph of a nude Kahlo.

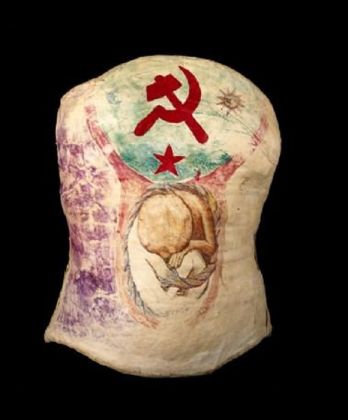

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón was born on 6 July 1907, to a Hungarian father and a Mexican mother. As a child Kahlo suffered from polio, leaving her with a stunted right leg, but worse happened when she was 18. A traffic accident left her with severe spinal damage and rendered her incapable of giving birth. The physical and emotional impact of the crash was to haunt her for the rest of her life. Visitors to the Rome exhibition are reminded of her suffering by the Plaster Corset in which Kahlo was entrapped from 1950. The hand-painted device features a hammer and sickle over an unborn baby, reflecting the blend of political and personal behind the artist who always wore her heart on her sleeve.

Kahlo's pain is evident in her Sketch for Henry Ford Hospital which refers to a miscarriage, her second, that she suffered in Detroit in 1932.

When she was 22 she married Rivera, 20 years her senior. This volatile relationship weathered Rivera's serial infidelities and violent temper, and Kahlo's bi-sexual affairs and poor health. The couple divorced in 1939 only to remarry a year later. Kahlo once said: “I have suffered two grave accidents in my life: one in which a streetcar knocked me down... the other was Diego.”

Kahlo's magnificent portrait of Rivera is juxtaposed by her unflattering caricature of her husband, a pudgy-faced ogre with bulging lips and crossed eyes. However her love for Rivera is clear in her paintings, many of which depict both artists in embraces, at one with nature, the sun, the moon, the planet, each other.

Among the highlights at the Scuderie is her Self portrait with Monkeys, a humorous comment on her relationship with her adoring students – who called themselves Los Fridos – at La Esmeralda art college in Mexico. The exhibition also includes a number of her watercolours such as Caballito Mexicano, a beautifully-painted rocking horse, or the curious Father Christmas character in San Baba, a caustic political critique about the bourgeois revolutionary leader and former Mexican president Venustiano Carranza.

Her contribution to surrealism is addressed with a series of works including the collage painting My Dress Hangs There in which the artist pines for Mexico after living in the US for three years with her husband. André Breton, founder of the surrealist movement, described Kahlo's art as a "ribbon around a bomb", but for Kahlo “surrealism is the magical surprise of finding a lion in the wardrobe where you are sure of finding shirts.” Perhaps she had this in mind when painting Window Display in a Street of Detroit, which features a lion, a white horse and a likeness of George Washington.

Towards the end of the exhibition is a room called The Diary 1946-1954 which provides an insight into Kahlo's private world. This section includes a deeply personal series of works created by Kahlo while at a Mexico psychiatric clinic following Rivera's request for a separation. Her friend, the young psychology student Olga Campos, encouraged Kahlo to process her suicidal feelings into her paintings in an attempt to cure herself through art therapy.

There is also a selection of beautiful photographs, in particular those by Nickolas Muray, featuring a rose-haloed Kahlo. Several of these images have become almost as iconic as Kahlo's paintings themselves, including Frida on White Bench, New York 1939 which appeared on the cover of the Mexico version of Vogue magazine in 2012. The exhibition ends with the artist's presumed last drawing, a self-portrait of a sad-eyed Kahlo with a dove nesting on her head and a lemniscate, or infinity symbol. Kahlo's diary reveals that the dove alluded to the poem La Paloma, by Spanish poet Rafael Alberti, which begins “The dove was wrong. The dove was mistaken.

To travel north she flew south.” Today, Kahlo's influence extends far beyond her assured place in art history, according to the exhibition's curator. Prignitz-Poda claims that Kahlo is a globally-recognised star whose image and first name have been branded similarly to Argentine Marxist revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara, as evidenced in Rome with La Casa di Frida on Via dei Falegnami 9.

Kahlo is also now regarded as a forerunner of feminism, a movement which has embraced her since the 1970s. The Rome exhibition is part of an integrated project with the northern Italian city Genoa which hosts Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera from 20 Sept-15 Feb. The Genoa show continues the story begun in Rome, focusing on the tumultuous marriage which shaped the paintings of Kahlo, a true artistic spirit whose short life was lived to the full.

Andy Devane

This article first appeared in the May 2014 edition of Wanted in Rome.

The exhibition at the Scuderie Papali is on until 31 August.

General Info

View on Map

Frida Kahlo in Rome

Scuderie del Quirinale, Via XXIV Maggio 16, tel. 639967500