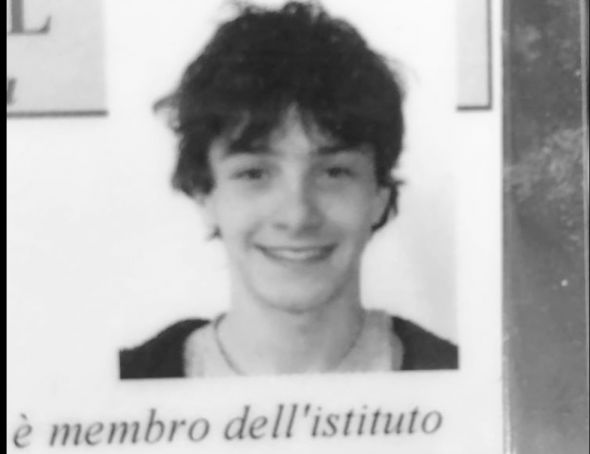

From empathy to action: Rome student reflects on his arc as an activist

By St Stephen's student H.D. Wright.

Manhattan

At 14, I had never met a refugee before. I could not even picture one. I had read numerous books and essays about the Syrian civil war and the myriad resettlement efforts spread across the Middle East; but the Syrian people had remained faceless to me, hidden beneath the weight of statistics and headlines endlessly siphoned across the borders of a restless and overstimulated world.

I knew that I would never be able to understand the conflict if I did not speak to the people it impacted, so, as the end of freshman year in school approached, I scoured the web for an opportunity to travel, and stumbled upon a trip, hosted by The New York Times, offering high school students the chance to travel across the cities of Germany with European economics correspondent Jack Ewing.

I knew that only a few years earlier, in 2015, Chancellor Angela Merkel had bravely forced open the gates of Germany to welcome over a million Syrian refugees to safety. I also knew that in response, the right wing pseudo-populist party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) had used their arrival to stoke the flames of xenophobic nationalism, earning 92 seats in the Bundestag the previous fall. I wanted to uncover the ingredients that had created such a corrosive concoction in German politics, so I applied. A few weeks later, I received an email notifying me that I would be flying to Berlin.

Berlin

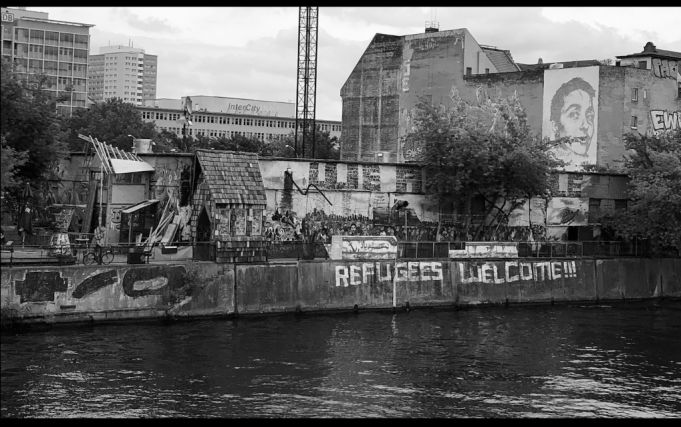

That first week, in bookstores and Biergartens along the banks of the Spree, the humanity that had been obscured was finally revealed. We met with refugees almost every day. Some were adults, others were only teenagers – but everyone had a story. I was amazed at how much they had weathered but astounded by how they had risen despite the weight of their circumstances.

In between these revelatory meetings, the other students and I wandered the winding streets of Berlin, Leipzig, Stuttgart and Munich, exploring the new neighbourhoods that had sprung up as a result of the resettlement effort. Vendors from Damascus sold food on empty street corners. Artists from Homs propped their art up against the grey walls. Music and crowds spilled out of restaurants, and delicious aromas from Idlib and Aleppo wafted behind them.

It was clear that areas that were once barren had been brought back to life, infused with a new cultural and economic energy. As a result, tourists flowed in from far and wide to participate in the wonders of this new cultural economy, further fuelling the engine of change, prosperity, and enrichment. To think that the builders of this new Eden had arrived empty handed, burdened down with the invisible weight of hatred; and they had built all of this.

Yet away from the colour and energy of these streets, between the cobblestones of Munich and beneath the plazas of Berlin, there slept an animosity, an anxiety that only dared to show its face behind the curtain of a voting booth, between the lines of an op-ed, and in the veiled gazes of angry pedestrians hurrying along the periphery. I could feel it in the air, but I couldn’t quite put my finger on what it was. I heard it in the whispers of those angry pedestrians; I saw it in their gazes, cast down at the sidewalk; but most of all I saw it in the physical separation between neighbourhoods, the invisible barriers erected between our world and theirs, dividing what was once one.

I wanted to understand the roots of this energy, comprehend why it continued to grow, as the subjects of its hatred helped the country flourish; so for my final project, I decided to probe deeper by interviewing Germans on the street. I approached them outside the Museum of Pergamon, between the columns of Brandenburg Gate, and on the steps of the Reichstag, and there I began to listen.

Some welcomed the refugees with open arms, others ambivalently, most begrudgingly, but among the voices of support and slight resistance, a cohort of a much darker nature began to take shape. They would often glance behind them, and then lean in, aware of the public shunning of their hidden views,

before speaking. Yet despite the worry, and the recognition of the unpopularity of their opinions, many came forward anyway. They told me that their culture was under attack, that their jobs were going to be stolen – that the very foundation of their identities was in danger.

Even though I had been given a personal look into the minds of those most impacted by the conflict, I felt there was still so much more to learn. I felt as if I had peered into an unimaginably deep crevasse and now I wanted to climb in. I promised myself that I would jump at the first opportunity that came my way. My sophomore year of high school, a chance to travel again finally came my way.

Rome

It was a Monday morning in Rome, and nearly six months had passed since I’d left Berlin and begun my sophomore study abroad at St Stephen's School. I had been in the Eternal City for only a few weeks when I heard that a local kitchen, staffed by Syrian refugees, was searching for volunteers. That very weekend, I took the train there, practicing Italian phrases in the corner of the train carriage. When I arrived, it became clear that my cursory level of Italian would not be enough to get by. I stacked supplies quietly in the corner, eager to find the keys to communication.

When I returned to school that evening, I signed up for two Italian classes, and petitioned for an independent study in Arabic. The weeks passed quickly, and soon the hours of quiet stacking were replaced with minutes of shy chatter. Then the minutes became hours, and the hours filled with stories. I learned that even though my new friends were thankful to be in Rome, their worries often brought them back to Syria, for many of their family members were stuck on a strip of sand on the Jordan-Syria border.

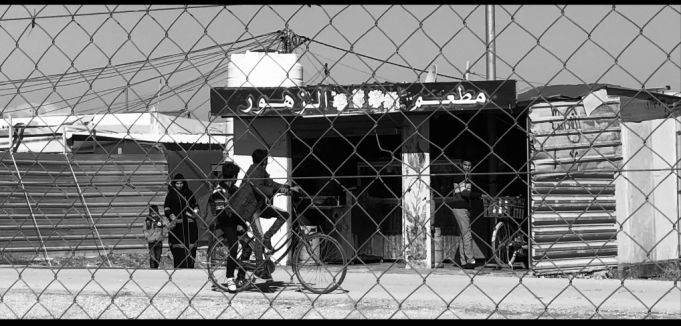

A few weeks later I learned that Jordan Hattar, a Syrian refugee activist, was visiting my school to speak about his experience working in Za’atari refugee camp, the very strip of sand my new friends had described. With each word, Jordan painted a picture of the camp and its inhabitants: the metal housing units stuck in the sand, the families waiting patiently inside them, and the tall gates and the barbed wire enclosing it all. As Jordan’s presentation came to a close, I wanted to ask him if he would take me there, but as the school filed out into the halls, he was lost among the crowd.

I trudged to the cafeteria and sat down at an empty table, sorely wondering if I’d missed my only opportunity to speak to him. As I cursed myself under my breath, a figure sat down across from me. I looked up from my tray, expecting to see a friend, but to my surprise, it was Jordan. For the next few months, as I finished my sophomore year of high school in Rome, and studied in New Haven and London over the summer, Jordan and I stayed in touch. After months of correspondence and planning, it was confirmed: we were going to Za’atari, the largest Syrian refugee camp in the world.

Za’atari

As our car edged closer, I glimpsed the outlines of the camp, a sea of white metal boxes spreading across the desert. Figures behind the walls of the camp came into focus, many of them children. And then we saw the camp's military guards, Jordanian soldiers dressed in combat fatigues, holding machine guns. After presenting our paperwork to the guards at the gates, we were ushered past the barbed wire and into the confines of the maze.

I stepped out of the car into a makeshift parking lot, noticing only four other cars, all owned by other NGOs. Only the click of my camera's shutter broke the silence, along against the wind." In a world of constant ‘breaking news,’ the stories of these refugees were being forgotten. The wire and the desert had forced the refugees into a state of isolated imprisonment, trapped between a painful past and an uncertain future, discouraged from following the road into Jordan, yet unable to retrace their steps back home.

Over the next few hours, I interviewed and photographed scores of families. Fathers told me how much they wanted to go back to work. Mothers told me how much they wished their children could go to school. And the children, approaching me with wide-eyes and smiles, asked for fist bumps and pictures, unaware of all that they had already lost. One theme traced a thread from family to family: the fervent wish to integrate into a new society and resume the rhythm of living.

After hours of hushed conversations, a soldier informed us that it was time to leave. We got back in the van and drove out through the gates, leaving this forgotten world behind in an unresolved cloud of dust. On the plane home, as we passed Cairo and glided over Rome, I thought about how far I had come, and how much farther I still had to go. I had dived into the crevasse, and learned that it wasn’t as terrifying as the news had led me to believe. How could I use the stories I had been told to make a difference? I wondered.

As 2021 came to a close, I found the answer thanks to my work with Kailash Satyarthi’s 100 Million campaign whose goal is to mobilise 100 million young people to push for a better future for 100 million marginalised children who have been denied their rights and liberty.

As a result of my involvement with 100 Million, I was invited to join the youth constituency of Education Cannot Wait, the UN’s new fund for education in emergency situations including war, climate disaster or any upheaval that threatens children's learning. I stood for election to represent the group, and I won.

Since then, I have reflected on the trajectory of my journey, and recognised the immense importance of listening to learn. I followed the words gifted to me in Berlin all the way to Rome; and as I carry out my duties at ECW, I will continue to do just that.

H.D. Wright

This article was published in the March 2022 online edition of Wanted in Rome magazine.