The National Etruscan museum in Rome’s Villa Giulia inaugurated four new exhibition spaces in mid-January dedicated to the ancient city of Veio, as well as opening the nearby Villa Poniatowski. Bought by the state in 1988 the 16th-century villa has since undergone an extended restoration programme and now houses Etruscan treasures from Latium Vetus and Umbria.

The building – named after its one-time owner Stanislao Poniatowski, nephew of the last king of Poland, who lived in Rome from 1754-1833 – is accessed from the Villa Giulia complex through Villa Strohl-Fern. Its frescoed rooms display artefacts dating from the tenth century BC. There are gold ornaments, pottery and weapons from the ancient towns of Alatri, Ardea, Tivoli, Lanuvio, Segni and Gabii. The highlight is the sarcophagus carved out of an oak trunk discovered in Gabii in 1989. On the ground floor is a library with more than 17,000 specialist volumes on Etruscan studies.

In Villa Giulia itself the large Veio rooms exhibit a wealth of Etruscan treasures, most of which have been kept in storage for the last 60 years. Items from the ancient city of Veio include funerary artefacts, bronze urns, intact and fractured terracotta, jewellery and weapons.

Further up Viale delle Belle Arti the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna (GNAM) reopened at the end of December after a six-week closure to reorganise its collection of 19th- and 20th-century art works. GNAM is noted for works by Amedeo Modigliani, Giorgio de Chirico and Renato Guttuso, while the many foreign artists include Vincent Van Gogh, Gustav Klimt, Jackson Pollock, Wassily Kandinsky and the American Cy Twombly, who died in Rome last year.

On this occasion, the gallery launched “100 Years at Valle Giulia”, a series of exhibitions celebrating the centenary of the building’s construction.

Although the gallery has been in its current location facing Villa Borghese since 1915, it was founded in 1883 after a temporary exhibition became permanent at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni on Via Nazionale. When there was no longer room for the burgeoning art collection, it moved to Cesare Bazzani’s spacious new gallery in Valle Giulia.

The gallery’s superintendent Maria Vittoria Marini Clarelli has been responsible for the renovations, which include improved lighting and colour schemes chosen specifically for each room. Alfredo Pirri’s installation Passi welcomes visitors as they walk across shattered mirrored-glass tiles to the sound of breaking ice, providing the disconcerting feeling of an imminent plunge into a freezing lake.

A tour of the gallery includes three chronological sections: 1800-1885, 1886-1925 and 1926-2000, as well as a special room called Scusi ma è arte questa? with works that once provoked scandal by Marcel Duchamp, Alberto Burri and Piero Manzoni.

Among the exhibitions is a show dedicated to the iconoclastic 1960s Arte Povera movement, part of several similar events taking place across Italy directed by its founder, Germano Celant. The exhibition pays special tribute to one of the movement’s chief exponents, Pino Pascali, by replicating a room dedicated to him in 1972 by Palma Bucarelli, the gallery’s legendary former superintendent and great admirer of the artist.

An exhibition entitled Art in Italy after the Photograph 1850-2000 examines the relationship between visual art and photography, while a retrospective of the work of 87-year old Livorno-based experimental artist Gianfranco Baruchello, who attended the reopening ceremony, is curated by Achille Bonito Oliva and includes over 60 of his works on loan from various European collections.

On the opposite side of Villa Borghese the city’s municipal Galleria d’Arte Moderna reopened in Via Francesco Crispi in November. Closed since 2003, the renovated gallery offers a comprehensive overview of the leading artists at work in the capital from 1880 to 1958.

Luoghi, figure, nature morte — the first in a series of rotating exhibitions — is divided into three thematic sections incorporating figurative art, views and visions of Rome, and still lifes. The exhibition showcases Italian art movements such as Novecento, Symbolism and Divisionism, and ends with a room dedicated to Futurist Giacomo Balla.

Arturo Dazzi’s highly-polished red marble Cavallino is at the junction of two narrow corridors surrounding a glass-framed cloister. Nearby is Giovanni Prini’s bronze statue of the Azzariti twin girls, whose innocence is overshadowed by Ercole Drei’s Seminatore, a decidedly fascist-looking statue of a larger-than-life peasant.

Upstairs, Afro Basaldella’s Composition depicts three figures relaxing amid lush vegetation, with rippling light effects captured in masterful brushstrokes. Mario Rutelli’s sculpture Naiad with a sea horse mirrors the figures in his controversial Fontana delle Naiadi in the capital’s Piazza della Repubblica, while Onorato Carlandi’s richly-painted Roman Forum contrasts with Francesco Trombadori’s desolate view of the Colosseum.

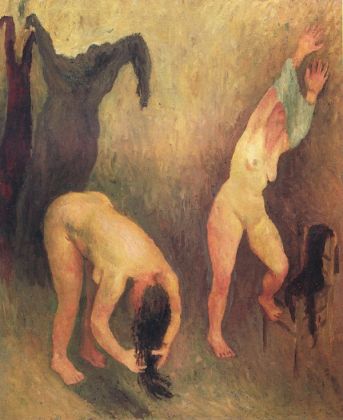

The Scuola Romana is represented by Mario Mafai’s 1934 painting Women Undressing, of two women struggling to undress while an ominous shadow lurks in the background. Together with his wife Antonietta Raphaël, in 1927 Mafai founded the Roman School at the couple’s home on Via Cavour. After their building was knocked down in 1930 to make way for the present-day Via dei Fori Imperiali, Mafai embarked on Demolitions, a series of paintings that reflected his criticism of the restructuring and extensive demolition of his native city by the fascist regime.

Palazzo Barberini also inaugurated a new space in December for temporary exhibitions with a major show dedicated to leading 17th-century Italian painter Guercino. The additional 1,000-sqm on the ground floor, formerly used as the Officers’ Club, makes the Barberini gallery the second-largest venue on the Roman museum circuit after Palazzo Venezia. Running until 29 April, the exhibition is a tribute to the Anglo-Irish art expert Sir Denis Mahon (1910-2011), who dedicated much of his 100 years to studying the work of Guercino.

Andy Devane