“There’s only one way to be creative: freedom. When you’re free to express yourself as you wonder you stimulate creativity”: here comes the voice of Gilberto Gil, one of Tropicalia’s heroes, the movement that reinvented the MPB (Musica Popular Bresileira) in the 1960s and 1970s just moving on the bossa nova wind whistled by their precursors.

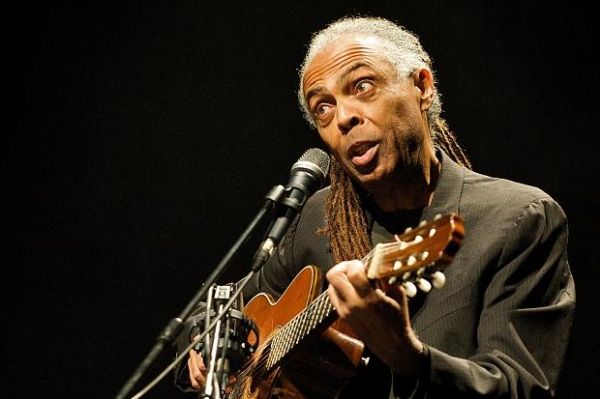

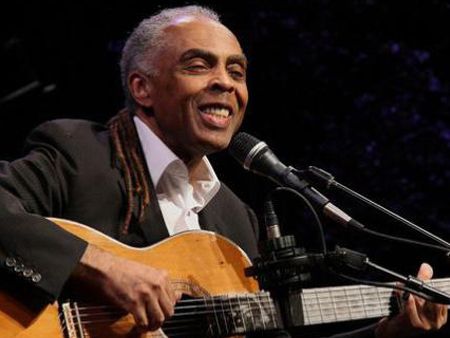

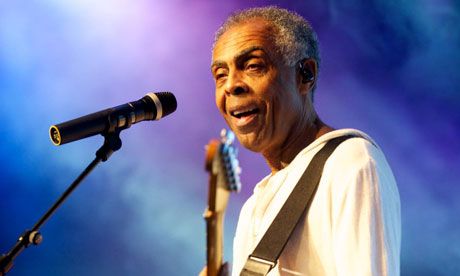

This 24 October he’s alone on the stage of the Auditorium della Conciliazione in Rome, the first step of his Solo Tour during which he is promoting around the globe his new album released last spring, Gilberto’s Samba. Alone with only his two guitars surrounding him and a repertoire that runs through the history of MPB, from the beginning to the most hybrid but still autochtonous tropicalist’s celebrations of Rio and Bahia.

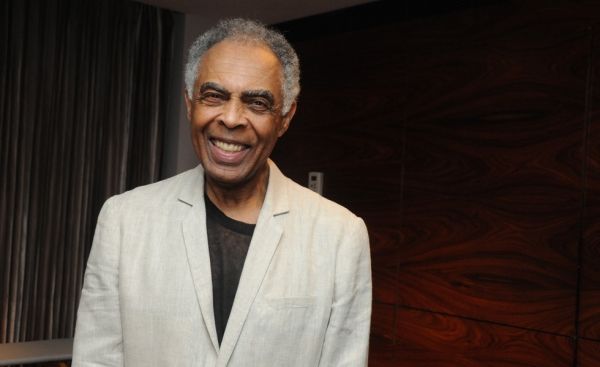

I was pretty excited when, shortly after his soundcheck, he turned his gaze on me and gave me the possibility of asking a few of the several questions I would have liked to ask. But time was running out. Now he’s 72, the white mane has replaced the dreadlocks he had in past years, but his eyes are the same of the younger Gilberto from Salvador who was exiled in England with his fellow Caetano Veloso because of their music that was too bold and libertine for the Brasil of 1969. The key to the Tropicalia revolution and its cultural innovation must be identified in the manifesto antropófago of José Oswald de Andrade Souza, the Brazilian poet that in the late 1920s was inciting to a cultural cannibalism, which meant: take the best from the whole world cultures and rework them in a higher form.

After 40 years of cannibalised music, you came back to the bossa nova

“Cannibalised sometimes and recycled other times. Just as art normally does with history, it takes things from the past and sometimes it destroys or uses parts of that. I think I’ve been doing this with the Movimento Tropicalia, but this record is exactly to tell people how the past has been important for us. The past that is too present to us like Joao Gilberto, the musician my album celebrates emphasising his influence and his style, his attitude and charisma. His secret profile as revolutionary artist has been so influential and important for my generation and the others after mine, not only in Brazil but everywhere. Not forgetting that he was doing exactly the same when he made his first three records: cannibalising some sounds from the past, using them differently, changing them completely in terms of concept and interpretation but, at the same time, showing great respect for the past and being bold enough to start things for the future. Like the bossa nova, the music from Tom Jobim and Vinicius de Morales. So we just followed that train.

Back to the roots to revitalise the musical identity of Brazil which is maybe changing and mutating his idioma?

You can find many reasons for choosing a project and a design like this. The bossa nova has been deeply important for us but today, in modern terms, what we historically called the Song has become something rare, something difficult to find. So, artists and writers, musicians and singers that can still dedicate some energy to the Song are keeping the song going on at least for a little more time, you know (he smiles)”.

A tribute to the past which was pure innovation. An innovation that was detected as "anti-musical”, the one that Antonio Carlos Jobim in his Desafinado was justifying as a “very natural and heart-coming” process. How did you choose the tracklist?

“First of all, identifying the bossa nova, and relative Joao Gilberto's tunes impressed me more. The ones that were well attached to my heart and my mind, to my affections and my memories. But there’s also Eu Vim da Bahia, the song I wrote myself and that was the only song of mine Joao recorded. And I chose Caetano Veloso’s Desde que o samba è samba, because of the touching nature of that song which belongs to the more recent Joao Gilberto’s repertoire. So, there were many many different reasons to choose this tracklist, but basically, what impressed me was the songs from the very beginning of Joao's work, they absolutely smashed me up when I first listened to them”.

Desafinado is the manifesto of bossa nova. But, despite the other tracks which don’t have particular sound effect tricks, we find in your record a sort of noise, like bowed strings in the red-hot air, simulating the pressure of thermometer deeply growing.

“Because it’s now! You can indentify it as you wish, but that sound sets the moment we are living is now. The producers of my album are my son Ben and Caetano’s son, Moreno Veloso. They are young guys doing music now, experimenting the new with the latest technological innovations. That effect shows respect for the new generations, for the elements that have been brought to music, all the experiments that have been done with electronic music, disco, deejaying, hip hop, and experimental music that generated new stuff. Modernising is still a form of cannibalism”.

Can we consider the Movimento Tropicalia as the basic of the following genres, as manifesto antropofago did with Tropicalia, thus Tropicalia did with Punk?

I think so. Considering the extention of the Tropicalia's impact on Brazilian music at that time, we can assume that everything came after tropicalia has something to do with it. Tropicalia was something that came, caused some noise, and of course, left its mark, some footsteps to be followed. Like the bossanova did with us and the same as what Tropicalia did fot punk, rock, reggae, hiphop movement in Brazil. 'Cause one of the things we were trying to say was that freedom is essential for creation and creativity and, of course, all the new creators that moulded have that element from Tropicalia, they have that in mind. We were working to be a little more free, so they do use this, the freedom to do new things, to experiment new experiences.

What remains of the protagonists of that movement?

We’re still very active. Tom Zè is still recording and performing, Caetano, Gal Costa, myself, all of us are all still in good shape. We’re still producing music and we’re still touched by these different elements of creativity. We still love music and the audiences very much as we like to please them, entertaining them, making them think, feel, and imagine. We carry on, we keep on going.

Somebody once said: “If music changes, istitutions will change too”.

“Sure, and vice versa: if the istitutions change music will change as well. It’s always an interactive process between things that are already established and things that are forcing the way to be established. They are not decreed yet, but they would be in a following moment. This dialogue is permanent, we are always, as you said, cannibalising and sacralising”.

Among the several questions I would have asked him was if he is still eating macrobiotic food since he turned in that diet during his London exile. But I think I got the answer just watching this marvellous man on the stage, all white dressed as those who get the illumination. And that, however, didn't lose a certain mood: perfoming the Pino Donaggio's song, "Io che non vivo senza te" in an adorable bossa nova key.

Federica Tazza - Repubblica XL