Generations of travellers on their Grand Tour have passed through the region of northern Lazio known as Etruria, briefly contemplating the abundant remnants of Etruscan civilization and Renaissance marvels before moving on to Tuscany or Rome.

The 1904 edition of Baedeker’s Central Italy has a few pages about Viterbo and the surrounding countryside. D. H. Lawrence mused on the tombs and complained about the food in Sketches of Etruscan Places, published posthumously in 1932; Kate Simon devoted a chapter to the area in Italy, the Places In Between, in 1970. But few narratives delve deeply into the complex layers of history that make Etruria a fascinating destination.

Historian, lecturer and writer Mary Jane Cryan has taken a special interest in the region, bringing to life the forgotten people, palazzi, villas and gardens scattered throughout the towns and countryside.

Her recent book, The Painted Palazzo/Il Palazzo Dipinto, complements her preceding collection of essays: Etruria – Travel, History and Itineraries in Central Italy. The latter book, filled with stories about Irish lords, exiled Stuarts, Americans romping in Renaissance fountains in the early 1900s, exiled Stuarts, and a world war two prison escape, ends with a description of the Palazzo Piatti in Vetralla and the extensive efforts to save it from ruin.

Piatti family

The Painted Palazzo begins with a more detailed look at the palazzo and the Piatti family who owned the building before it fell into disrepair. The author then takes the reader on another excellent tour of lesser-known sites. The illustrated book, written in both Italian and English, is ideal for those learning either language, and for tourists who are interested in knowing more about this small part of Italy, so close to Rome yet often ignored.

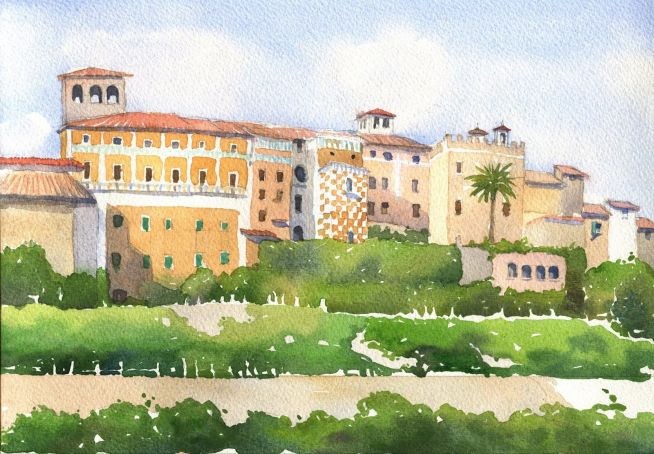

Early photos of Vetralla show the town dominated by an enormous building consisting of 85 rooms on five levels fronting on the Via Cassia, the old Roman consular road. This is the Palazzo Piatti, purchased by the family in 1893. Its origins are unknown but probably mediaeval as it incorporates walls that enclosed the town during that period.

The Piatti were engineers and builders from Piedmont where they had been a prominent family since 1560. The family construction firm played a large part in the development of railroads in Italy from the mid-19th to the early 20th centuries.

They became wealthy property owners, purchasing palazzi in Piedmont, Liguria, Lazio and Rome, as well as more than 5,000 hectares of agricultural land around Viterbo and Vetralla.

Ligurian décor

The family favoured décor popular in Liguria, using it at their villa in the town of Quittengo near Biella. The redecoration of the Palazzo Piatti replicated the style with interiors painted in floral designs, examples of which remain, along with scraps of other frescoes more evocative of Lazio with its cypress and umbrella pines. The exterior was a startling mix of trompe-l'œil and checkerboard, unfortunately now faded away.

Part of the palazzo served as barracks during world war one. Later it became a home for one of the two heirs to the Piatti fortune when Flaminio married Olga, the daughter of the famous sculptor Pietro Canonica, who had a house and studio in Vetralla. The couple lived a life of luxury, wasting much of their fortune on gambling.

By 1929, portions of the building had to be sold to pay their debts. Ten years later the remainder passed from the family hands and The Piatti family faded into obscurity.

The building became a club for members of the Fascist party and their families and living quarters for homeless families during and after the war.

Following this period, it was divided into apartments and sold to local farmers. Sections were completely abandoned. It became a safety hazard when rain seeped through the roof, dead pigeons rotted on the upper floor, tiles dangled from rotten gutters, chimneys cracked and building materials were removed illegally.

New lease of life

The wheel of fortune turned again in 1993, when newcomers, including Mary Jane Cryan, began to purchase the apartments. Battling bureaucratic inertia and reluctance of former owners to improve the property, the newcomers, who appreciated the building’s history and its remaining frescoes, put their energies into restoration. Over time, the building has been stabilised and much of its past salvaged.

In addition, the extensive terraced gardens have been rebuilt. Banana trees and oranges grow at the warmest upper level; persimmon, kiwi, medlar, umbrella pine and fruit trees flourish on the middle levels; hazelnut on the lowest and coolest terrace. A restored orangerie hosts musical performances put on by the musical organisation OperaExtavaganza.

Piatti legacy

The legacy of the Piatti family remains in other nearby locations. Flaminio commissioned the architect Marcello Piacentini, famed for his modernist buildings during the fascist era, to build a neo-classical villa near Vetralla in 1925. But Villa Carmine met the same fate as Palazzo Piatti when Flaminio sold it to his father-in-law, Canonica, to pay his debts. Canonica later sold it to the Carmelites who remain the owners, although the outbuildings now serve as the Pro Loco and senior citizens club while the grounds host the town park and sports facilities.

Bisentina Island

A more romantic and durable memory of the Piatti family is the island of Bisentina in Lake Bolsena. The family held the rights to the island from 1899 to 1912, and used their talents and money to restore a crumbling monastery and established a botanic gardens full of exotic plants.

The second half of The Painted Palazzo consists of other vignettes about recent discoveries and locations worth a visit – who wouldn’t want to see Easter Island sculptures* in the tiny hill town of Vitorchiano?

Anyone looking for material for a novel would be interested in the discovery of several images of Giulia (la Bella) Farnese, whose “attachment” to Rodrigo Borgia (Pope Alexander IV) helped further brother Alessandro Farnese’s career as he ascended the career ladder to become Pope Paul III. All portraits of her were previously thought destroyed to hide a scandalous life, surely no worse than others in the family.

Ortensia Farnese

Another Farnese woman whose image has recently come to light is that of Ortensia Farnese. After dispatching three husbands and being accused of poisoning her own daughter, she became known as the “Lucrezia Borgia of Parrano.” The two paintings in Vetralla show her as a black-veiled penitent. Light punishment for a murderer, and fodder for a novel indeed.

I was particularly interested in the ruins located at Ferento, mentioned in the book, the Etruscan/Roman city of Ferentium, as seen through the eyes of travellers from the 18th century onwards.

It was inhabited until the Middle Ages when the good citizens of Viterbo reportedly destroyed it over the offense of a crucifix designed with Christ’s eyes open instead of shut. Now it’s a little-visited archaeological site hosting an amphitheatre and a few other semi-ruined buildings. The ancient Roman road running through the remains of the town is rutted with cart tracks. Did travellers pass by the Palazzo Piatti on their way visit the ruins before moving on to Rome?

One of these travellers, James Sully, recorded his impressions after he visited Ferento. In a book published in 1912, Sully sniffed: “He will do well to visit other towns which had hostile doings with Viterbo: …Vetralla where, though there is little of interest in the squalid-looking town, the visitor may walk over to the romantic valley of Norchia, and see the long series of lofty, temple-like Etruscan tombs carven on the face of the warm yellow cliffs.” Well, now we know he was wrong. If only he’d had this entertaining book in hand he’d have had a far better impression.

*Moai di Vitorchiano

The world's only Maoi statue outside Easter Island is located in the mediaeval village of Vitorchiano, near Viterbo. The colossal sculpture was carved in 1990 by 11 indigenous craftspeople from Easter Island using traditional axes and sharp stones, as part of the Italian television documentary Alla ricerca dell'Arca (In search of the Ark). Vitorchiano was chosen for the unusual initiative because it was discovered to contain a similar volcanic rock used in the original Easter Island statues, whose origins remain shrouded in mystery. The sculpture weighs about 30 tons, is 10m high, and can be found on the road leading to Grotte S. Stefano just outside the centre of Vitorchiano.

Both The Painted Palazzo and Etruria are published by Edizioni Archeoares in electronic format (€5.99) or paperback (€10). The paperback can also be ordered directly from the author’s website or found in various bookshops in Etruria. It is available in Rome at the Anglo-American Bookshop, Via delle Vite 102. Cryan’s other books are available from her website.