How a statue of an ancient Greek mythological figure attracted the attention of Rome's Renaissance masters and the Vatican

For every wonder Rome houses above ground, who knows how many more lurk below. Its soil teems with dormant statues, waiting, like Museo Nazionale’s famous boxer, to see again Dante's “sweet light of day”. It might take centuries or millennia; suddenly they resurface.

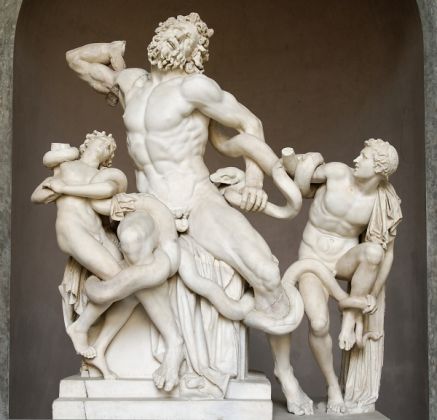

So it happened in 1506. In a vineyard on Colle Oppio where Nero once had his palace, up from beneath came not one statue but a stage set in marble. More newsworthy still was that to supervise the excavation was not only Pope Julius II’s architect Sangallo but also his favourite sculptor-turned-painter Michelangelo. One figure, two figures, a larger than life-sized third, then two snakes rippling fatally between the three: Laocoön, as Pliny the Elder had described the same group after a visit to the house of Titus. Again getting his history dead on, Pliny located the work in the same spot where, eager to erase Nero’s memory, Titus (together with his Flavian father and brother) had rebuilt an imperial palace of their own.

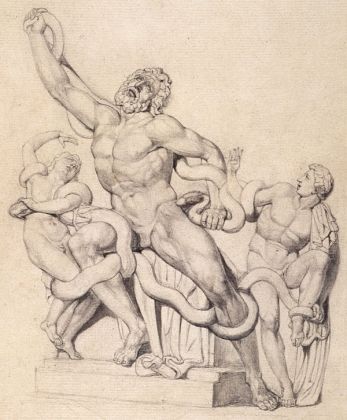

One theory is that the work was created by three sculptors from Rhodes centuries before being shipped to Rome as imperial booty. Another that it was a copy of a bronze statue from the ancient Greek city of Pergamon. William Blake, for his part, insists that yes, it was a copy – an inferior one at that – but of a statue from Jerusalem’s Temple, sacked by Titus before he became emperor. In Blake’s own drawing of Laocoön, the poet with typical eccentricity includes a plaque stating that the three figures represented are not Greek at all, but Adam and Satan while in the centre is Jehovah himself.

But to get back to 1506: the statue once unearthed, Pope Julius II knew a good garden decoration when he saw it and earmarked the statue for his recently-built Belvedere in the Vatican. The one problem was that Laocoön’s right arm was missing. With Michelangelo’s arch-rival Raphael as one of the judges, the pope ordered a sculpting competition for the missing limb. Most theorised that the arm would have been outstretched according to heroic convention. Drawing perhaps from his anatomical knowledge, hard won from long nights in S. Spirito’s morgue, Michelangelo begged to differ; he insisted that Laocoön’s arm would have been, if only for anatomical reasons, drawn back. The heroic outstretched arm-transplant won the day. And so for centuries it remained attached in heroic fashion.Then in 1906 an itinerant archaeologist – one Ludwig Pollak – entered art history. Rummaging in a builder’s yard near the Capitoline, he found an arm. Its drawn-back shape was exactly as Michelangelo had not so much guessed as knew. As if those writhing ignavi or musclemen on the Sistine ceiling are not enough, here’s more proof of his flawless anatomical judgment – a twist not of fate but of genius. The arm was sent to the Vatican, only to be stored away for 50 years. Then it was brought out again, dusted off, stuck back on – a perfect fit.

If every picture tells a story, so do sculptures. Imagine yourself in Troy. The Greeks have been attacking day in day out for ten years. One dawn the Trojans wake up. There’s no enemy in sight, only this gigantic wooden horse. Peace at last. The Trojans sortie out to investigate. Mostly convinced that the Greeks have gone for good, they start debating about the horse and what to do with it. Someone suggests bringing it into town. In rushes Laocoön, priest of Neptune, Troy's tutelary god. “O wretched countrymen! what fury reigns? / what more than madness has possessed your brains,” Dryden drops a perfect couplet into his mouth. “Have you forgotten the tricks of Ulysses? Either the horse is a spying device, or else the enemy are hidden inside. Beware of Greeks bearing gifts,” Laocoön warns famously. Alas for them, the Trojans don't listen.

Onto the scene sidles one of literature's all time villains, Sinon the simulator. A Greek double agent who can lie like truth, he claims refugee-status, begging the Trojans for asylum. Fear not, he assures them. My countrymen have sailed away. It's peace in our time. I should know. I’m the wretch they chose to sacrifice to secure them a safe journey home. Only, fortunately, I escaped. As for the horse, no worries there either. It's an offering to Athena, the Greeks’ patron goddess. “But why’s it so big?” objects a Trojan. Up his sleeve Slippery Sinon has the answer: To stop it being hauled into Troy, for once the Trojans do that, the Trojans will become invincible; and Athena will switch her allegiance to the Trojans, allowing them to conquer Greece as the Greeks tried to conquer Troy.

As if this is not persuasive enough, up from the sea rear “Two serpents, rank'd abreast.” Trojans scatter, the snakes attack and consume Laocoön’s two sons; then they target Laocoön himself. So Athena, whose offering of the wooden horse Laocoön rejected, is avenged.

That’s the standard version. Another is that Laocoön’s offence is less against Athena than against Neptune. Despite being Neptune’s priest, he had angered the sea-god by not being celibate. Worse, at some point he had made sacrilegious love before the altar. Laocoön is justly doomed to die, proclaim the Trojans.

From one viewpoint the Laocoön story is tragedy: the just and honest man betrayed by fate. Yet from a Roman viewpoint it’s also cause for celebration. Consider the scenario had events been different. Had the Trojans heeded their priest’s advice, the crafty Greeks would have been discovered, Troy would not have burnt and Virgil's mythical Aeneas would not have set sail across the Mediterranean to land in Italy. Without him there would have been no Romulus and Remus, no Rome, no Augustus, no empire, no unearthing of the statue on the Colle Oppio, no standing in the Vatican’s octagonal room admiring what Pliny described as “the statue of statues”.

Nor in 1799 would soon-to-be-emperor Napoleon have carted the work off to Paris where, once safely installed in the Louvre, it inspired French neoclassicism. None too soon, given that with Napoleon’s defeat the statue was brought back to Rome.

To return to Michelangelo, without Laocoön the first panel of the Sistine Chapel might not have taken the same shape. Look up at God dividing light from darkness. In part the Creator's tortuous stance in the fresco replicates muscle for muscle the Laocoön unearthed just years before. Also one cannot ignore an autobiographical element, the posture which Michelangelo up on his scaffold was also forced to adopt for the three years before completing his own work to completion. To quote his sonnet:

Drip-drop-drip: Paintbrushes without cease

Convert my face to multi-coloured floor.

Groin threatens mid-riff with a takeover;

Arsy-versy, my rump’s the counterweight.

Eyesight battling posture, do I come or go?

My skin in front stretches against Nature;

Spinal cord has got folded into this knot

And draws me like a Syrian his bow.*

But for dripping paint, it takes only a skip of imagination to see in the figure portrayed Laocoön’s double. *

Translation by Martin Bennett from – Michelangelo Buonarroti, Sonnet V (to Giovanni da Pistoia)(ca. 1509).

Martin Bennett

This article appeared in the 4 February print edition of Wanted in Rome.