Mount Vesuvius, one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world

If you have been to Napoli, you've surely noticed Mount Vesuvius towering over the city.

The mountain is an unmistakable landmark of the Bay of Naples, and its beauty is captivating. However, it is as beautiful and spectacular as it is dangerous. You only have to do a small look into the history of Vesuvius to realize the destruction that it is capable of. The nearby ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum are grim reminders of the destructive power that Vesuvius is capable of unleashing.

Vesuvius is the reason we use the term Plinian eruptions to describe particularly violent and explosive volcanic eruptions that the mountain is known for, as are others all around the globe. The term comes from the famous Pliny the Younger, a lawyer, author, and magistrate of ancient Rome, who witnessed the mountains famous eruption in 79 AD, in which his uncle was killed.

While the eruption in 79 AD that destroyed the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum may be the mountain's most famous eruption, it is not the only or even the most destructive eruption in history.

Today, Vesuvius is considered to be one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world. It is the only volcano on the European mainland to have erupted in the last hundred years (with Etna of course being on the island of Sicily). Around 3 million people live near enough to the volcano to be affected by an eruption, with around 600,000 living in the danger zone, making it the most densely populated volcanic region in the world.

History of the Vesuvius vulcano

Formation

Mount Vesuvius was formed as a result of a collision between the African and Eurasian tectonic plates, with the former being subducted beneath the latter. It is one of several volcanoes that form the Campanian volcanic arc.

The other volcanoes include Campi Flegrei (Phlegraean Fields) a large caldera to the northwest, Mount Epomeo, 20 kilometers (12 miles) to the west on the island of Ischia, and several other undersea volcanoes to the south.

While some of the others have erupted in the last few hundred years, Vesuvius is the only one that has erupted in recent history. Many of the others are extinct and have not erupted for thousands of years.

Mythology and Etymology

Vesuvius has a very long history in mythology and literary tradition. At the time of its eruption in 79 AD, it was considered to be a divinity of the Genius type. Decorative frescoes on many lararia or household shrines found in the ruins of Pompeii show the depiction of a serpent with the inscribed name Vesuvius and was worshipped as a power of Jupiter.

According to the Romans, Mount Vesuvius was devoted to Hercules. While any facts behind the tradition remain unknown, an epigram by the poet Martial from 88 AD suggests that both Venus and Hercules were worshipped in the region that was devastated by the eruption nine years earlier.

The origin of Vesuvius' name is disputed. During the Roman Iron Age, many people from different ethnicities who spoke different languages occupied the region of Campania. So, the origin of the name varies depending on the assumption of what language was spoken there at the time. Naples was originally settled by the Greeks, who gave it the name Nea-polis, "New City."

However, others such as the Oscans, an Italic people, lived in the countryside, while the Latins also competed for the occupation of the region, and Etruscan settlements were also in the vicinity. Therefore, the origin of the name is tricky to pinpoint, but the name Vesuvius was used frequently by authors in the late Roman Republic and the early Roman Empire.

Eruptions

Avellino Eruption

Mount Vesuvius erupted many times before 79 AD. Evidence suggests that some of the earlier eruptions were far more violent and destructive than the one that destroyed Pompeii and Herculaneum. Perhaps the most famous of these is known as the Avellino eruption.

The date of the Avellino eruption is disputed, but most estimates place it within a period of 500 years in the Early/Middle Bronze Age, around 2000-1500 BCE. The power of a volcanic eruption is measured on a scale known as the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI). It is estimated that the Avellino eruption had a VEI of 6, more powerful than the eruption in 79 AD that had a VEI of 4.

Pumice deposits from the eruption can still be found in the comune of Avellino in Campania. In May of 2001, Italian archaeologists discovered remarkably well-preserved remains of a Bronze-Age settlement at Croce del Papa near Nola that was destroyed by the eruption.

The remains include huts, pots, livestock, as well as footprints of animals and people, and skeletons. The footprints found suggest that the residents hastily abandoned the village, while the remains were buried and preserved under a layer of ash and pumice. Much the same way that the remains of Pompeii and Herculaneum were later preserved.

79 AD (Pompeii and Herculaneum)

The most famous eruption of Mount Vesuvius occurred in 79 AD and destroyed the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. One of the deadliest eruptions in European history, over 1,500 human remains have been found at the sights of Pompeii and Herculaneum so far.

While the total death toll remains unknown, some estimate it to be as high as 16,000, as the total population of both cities at the time was around 20,000. Traditionally, the exact date of the eruption is thought to be the 24-25 of August, however, modern hypotheses have suggested it may have occurred in October or November.

Several precursor events lead up to the eruption. The first occurred on February 5th, 62 AD, when a major earthquake struck the region for the first time since 217 BC. The earthquake caused widespread destruction in the Bay of Naples, as well as the deaths of 600 sheep from "tainted air", a sign that the earthquake may have been related to new activity by Vesuvius. A much smaller earthquake occurred in 64 AD and was recorded by Suetonius in his biography of Nero, and by Tacitus in Annales.

At the time, Nero was in Naples, performing for the first time in a public theatre. According to Suetonius, the emperor sang through the earthquake and finished his song. Then, according to Tacitus, the theatre was evacuated and collapsed shortly after.

Then, in 79 AD, small earthquakes could be felt for four days before the eruption. However, because minor earth tremors were so common in the area around Mount Vesuvius, they were not taken as a sign of any impending volcanic activity.

The eruption would last for two days. The only eyewitness that would leave a surviving document was Pliny the Younger, who had been staying at Misenum on the other side of the Bay of Naples. He recalls the morning of the fateful day had started as any normal day.

Though Pliny the Younger was staying far enough away from the volcano, 29 kilometers (18 miles), and was not able to talk to anyone who had witnessed the eruption from Pompeii or Herculaneum, so it is possible that there were earlier signs.

Mount Vesuvius began violently erupting around 1:00 pm, spewing a deadly could of ash and pumice along with super-heated tephra and gases to a height of 33 km (21 miles). The volcano ejected the molten rock, pumice, and hot ash at 1.5 million tons per second, ultimately releasing 100,000 times the thermal energy of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

During the night and early into the second day, pyroclastic flows, a current of hot gas and volcanic matter that flows along the ground away from the volcano and can move at immense speeds began. The flows moved so rapidly that they knocked down all structures in their path, and anyone caught in the current was incinerated or suffocated. The currents altered the landscape and coastline and were accompanied by more light tremors and a small tsunami in the Bay of Naples.

By the evening of the second day, the eruption was over. Pliny the Younger wrote an account on the eruption: “Broad sheets of flame were lighting up many parts of Vesuvius; their light and brightness were the more vivid of the darkness of the night… it was daylight now elsewhere in the world, but there the darkness was darker and thicker than any night.”

Later Scientific Analysis

Reconstructions of the eruption have varied greatly in the details, however, the same overall features have remained consistent. The eruption lasted two days and was a multi-phase eruption, alternating six times between the highly explosive Plinian eruption and Pelean.

The initial eruption produced a cloud of ash and pumice that rained down on Pompeii, but not on Herculaneum which was up-wind. Eventually, the cloud collapsed as it became so large and the gases within could no longer support the solid contents within.

This resulted in the pyroclastic surge which reached Herculaneum first, but not Pompeii. However, additional blasts reinstituted the column, and it is believed that blasts 3 and 4 buried Pompeii. The gases from these surges have been estimated to have reached temperatures as high as 300C (572F), making it impossible for any remaining citizens to escape.

The Two Plinys

The two letters written by Pliny the Younger to the Historian Tacitus are the only surviving eyewitness accounts of the eruption. In the letters, Pliny the Younger describes, among many other things, the last days of his uncle Pliny the Elder. Having witnessed the eruption from Misenum on the other side of the Bay of Naples, the elder Pliny, who was a naval and army commander in the early Roman Empire, launched a rescue fleet and went himself to rescue a personal friend. His nephew declined to join him but was able to discover his uncle’s experiences from witnesses, which he wrote about in his second letter.

Aerial view at ruins of Pompeii. Ph: Marcin Babul / Shutterstock.com

He describes how his uncle, who was in command of the Roman fleet at Misenum, ordered a rescue operation by sea. His nephew tried to resume a normal life after his departure, but the situation was growing far worse. That night a tremor awoke him and his mother, who insisted that they abandon the house for the courtyard.

The next morning the young Pliny saw lightning in a dark cloud that was obscuring the morning light. The population began to evacuate from the coast, as a thick cloud of ash began to fall on the village. The young Pliny at one point had to shake it off to avoid being buried. Later that day, the ash stopped falling and Pliny and his mother returned home to await news of Pliny the Elder.

Meanwhile, Pliny the Elder had received a message from his friend Rectina (wife of Tascius) who was living near the foot of the volcano. They were on the other side of the bay and in desperate need of assistance, as their only chance for evacuation was by sea. He set off across the bay and encountered thick showers of hot cinders, lumps of pumice, and pieces of rock.

His helmsman advised him to turn back, to which he responded "Fortune favors the brave" and ordered him to continue towards the town of Stabiae, 4.5 kilometers from Pompeii.

When they arrived, they saw flames coming from the crater. After staying overnight, they were driven from the building after an accumulation of tephra threatened to block all escape. They woke Pliny and took to the fields with pillows strapped to their heads to protect them from raining debris.

When they approached the beach again, the wind was preventing the ships from leaving. Pliny the Elder lay on a sail that had been put out for him, from which he could not rise, even with assistance.

His friends managed to make it out alive, though Pliny the Elder died. His body was found the next day with no apparent injuries. In Pliny the Younger's letter to Tacitus, he suggested that his uncle died after inhaling too much toxic gas. However, this seems unlikely considering that no one else in the party was affected. It is more likely that he died of a stroke or a heart attack.

Casualties

The total number of casualties is unknown. By 2003, 1,044 casts made from impressions of bodies have been found around Pompeii, with another 332 found at Herculaneum. Around thirty-eight percent of the bodies found in Pompeii were inside buildings and most likely died when the roofs collapsed. The remaining sixty-two percent were found in pyroclastic surge deposits and died due to suffocation from ash and from debris that fell on them.

Thanks to the direction of the wind, Herculaneum, which was much closer to the crater, was saved from the tephra falls. Instead, it was buried under 23 meters (75 ft) of material from pyroclastic surges. It is estimated that all the victims from Herculaneum died as a result of these surges.

Eruptions After 79 AD

Vesuvius has erupted about three dozen times since 79 AD. In 472, it released such a large amount of ash that ashfalls were reported as far away as Constantinople (1,220 km, 760 mi). Further eruptions recorded the first known lava flows from the volcano. It became quiet however at the end of the 13th century, in which time gardens and vineyards began to cover it.

Then, in December of 1631, Vesuvius erupted violently once again. This eruption buried many surrounding villages in lava flows, resulting in the deaths of about 3,000 people. From then on, eruptions have occurred regularly.

Vesuvius has erupted several times in the 20th century, with the first happening on the 5th of April, 1906. This eruption killed more than 100 people and ejected the most lava ever recorded from a Vesuvian eruption. At the time, Italy was preparing to host the 1908 Summer Olympics, but after the eruption caused devastating damage to the city of Naples and other surrounding comunes, funds were diverted to reconstructing the city and a new venue was found.

Since 1750, seven of Vesuvuis' eruptions have lasted longer than five years, more than any other volcano except Etna. The two most recent eruptions, 1875-1906 and 1913-1944, both lasted longer than thirty years.

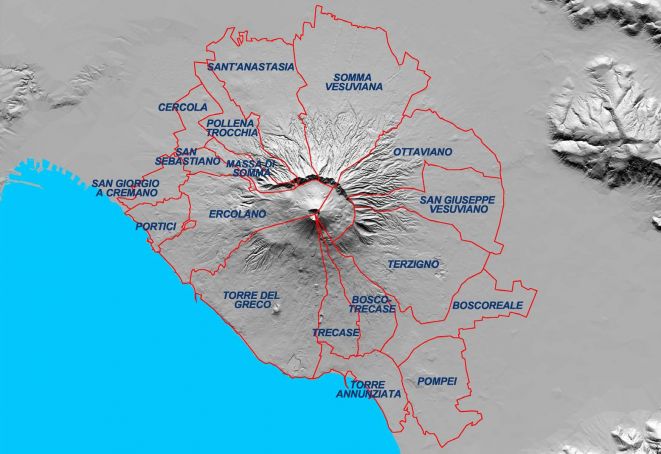

Vesuvius erupted again in 1913 and remained active until 1944. For many years, lava could be seen filling the crater, spilling out the side on some occasions. This period of continuous eruption ended with a major eruption in March of 1944, which destroyed the villages of San Sebastiano al Vesuvio, Massa di Somma, Ottaviano, and parts of San Giorgio a Cremano.

The destruction was mostly due to lava flows, but then on the 24th of March, an explosive eruption resulted in a small pyroclastic flow. At the time, the United States Army Air Forces 340th Bombardment Group was stationed at Pompeii Airfield near Terzigno, just a few kilometers from the eastern base of the volcano. The hot ash and tephra from the eruption destroyed between 78 and 88 aircraft.

Present Day and Future

The eruption in 79 AD that destroyed the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum is the most recent large Vesuvian eruption.

The size of the eruption is based on how much volcanic material is released. A large eruption occurs when quantities of about 1 cubic kilometer of volcanic material are released.

Scientists estimate that these eruptions occur once every few thousand years, while the medium-sized, sub-Plinian eruptions in which about 0.1 cubic kilometers of material is released occur every couple hundred years such as the ones in 472 and 1631. Smaller eruptions occurred frequently from 1631 to 1944, in which only a small amount of volcanic material, about 0.001-0.01 cubic kilometers of material was emitted.

In the event of an eruption, the government's emergency plan assumes that the worst-case scenario would be an eruption with similar power to the one in 1631, which was measured to have a VEI of 4. The area around the volcano is now densely populated, and estimates suggest that anyone within a 7 kilometer of the vent could be exposed to pyroclastic surges, with other surrounding areas being vulnerable to tephra falls.

The prevailing winds that sweep through the Bay of Naples put the towns and cities to the south and east of the volcano at the highest risk. For the city of Naples to the northwest, the risk of tephra falls is much lower and experts don't think it would spread past the slopes of the volcano.

The evacuation plan that the government has in place assumes that they will have between two weeks to twenty days to react to an impending eruption. In the event of an evacuation, some 800,000 people living in the zona rossa (Vesuvius red zone) would be evacuated.

The red zone comprises 25 comunes and part of the city of Naples. The evacuation is planned to take about seven days and would involve many evacuees being sent to other parts of the country where they could remain for months. The dilemma that the authorities face, however, is when to start the evacuation process.

If they start it too late, thousands could be killed, but if they start too early and the eruption ends up being a false alarm, then it could have repercussions as well. The last evacuation turned out to be just that when in 1984, 40,000 people were evacuated from the Campi Flegrei area, but no eruption ever occurred.

Italian authorities, especially in Campania, are implementing ongoing efforts to try and reduce the population in the red zone. This involves demolishing illegally constructed apartment buildings, establishing a national park around the volcano to prevent any further structures from being built, as well as offering people significant financial incentives for moving away.

The overall goal is to reduce the amount of time needed to evacuate the population. Authorities hope to reduce this time by two or three days in the next twenty to thirty years.

The red zone around Mount Vesuvious.

In Naples, the Osservatorio Vesuvio (Vesuvius Observatory) closely monitors any activity in and around the volcano. Using extensive networks of seismic and gravimetric stations, a combination of a GPS-based geodetic array and satellite-based synthetic aperture radar to measure ground movement, and local surveys and analyses of gases emitted from fumaroles, the volcano is under constant surveillance.

This technology is all used to detect any rising magma underneath the volcano. For the moment, no magma has been detected within 10 km of the surface, meaning it is currently classified at a Basic or Green Level.

General Info

View on Map

Mount Vesuvius, one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world

Vesuvio, 80044 Ottaviano NA, Italia