The colourful stories behind the final painting by High Renaissance master Raphael.

If every picture tells a story, then The Transfiguration by Raphael on view in the Vatican Museums tells several. There is the story of the events portrayed, as well as the history of the canvas itself and its strange role in the life of the artist who created it.

The painting was commissioned in 1517 by Cardinal Giulio Medici. You might already know him: in Raphael’s portrait of the Medici Pope Leo X, Giulio is the tall, handsome cousin standing on the left. By setting one artist against another the Medici, as patrons of the arts, had learned that there was nothing like competition to optimise results. This time Raphael was called on to paint The Transfiguration and Sebastiano del Piombo from the rival Michelangelo camp to paint Lazarus rising from the Dead, both works for the altar of Narbonne cathedral, where Giulio was then bishop.

A year passes, and no painting – though it’s true that Raphael, “prince among artists”, had no shortage of other duties. As the recently appointed papal architect he was responsible for redesigning St Peter’s after the death of Bramante, as well as being superintendent of antiquities. Another year passes; still no painting. In 1519 del Piombo completes his own part of the commission, thanks to drawings supplied by Michelangelo, and given that Raphael’s work is still not forthcoming, he declares himself victor.

Then in 1520, in the run-up to Easter, Raphael suddenly falls ill. Vasari, always eager for a juicy story, opines that it was caused by excessive lovemaking with La Fornarina – Margarita Luti – Raphael’s long-term lover. The doctor, however, diagnoses heatstroke. Raphael who, according to Vasari, also nursed hopes of becoming a cardinal, declines to correct the doctor and so carries on with the wrong treatment. The night of Good Friday is, tragically, his last. There at the bed’s foot, at long last, is The Transfiguration: the radiance of the upper part of the picture is all the more striking for the chiaroscuro of the scene below as the disciples try in vain to enact a miracle.

The papal court goes into mourning. As his funeral cortege of “a hundred painters” processes to the Pantheon, Raphael’s requested resting place, the painting is hoisted up in the front the procession before being set behind the altar. It makes a neat finale, although another version of the story, backed up by restoration work in the 1970s, suggests that some figures in the painting’s bottom left were added later by Raphael’s long-term collaborators Giulio Romano and Gianfresco Penni.

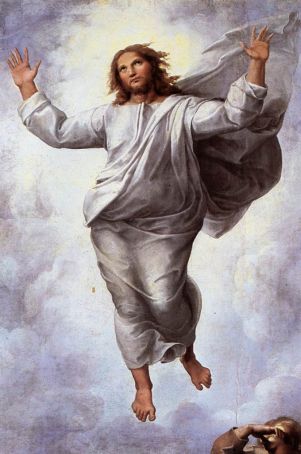

But what of the story depicted in the painting itself? Or stories, given that it incorporates two halves. First the upper half or the Transfiguration, which St Thomas Aquinas described as “the greatest miracle of all”, unique in that it happened not to others but to Jesus himself. “And his face shone like the sun, and his raiments were as white as the light,” to cite St Matthew.

Raphael depicts Christ with his arms raised, so prefiguring the Crucifixion. In addition the Christ figure floats in air, evoking the subsequent Resurrection. To his right Moses bears the Tablets of the Law, to his left Elijah the books of prophecy, one of which (Malachi) cites Elijah’s reappearance as a precondition for Christ’s coming.

Lying below are James and John, then Peter in the centre. Only Peter has his eyes open, as later described in his second Epistle: “Not out of cunningly designed fables do I tell you these things, but as an eyewitness unto majesty.” Almost offstage are St Pastor and St Just, the patron saints of Narbonne whose feast day, 6 August, coincides with the feast of the Transfiguration, a date chosen to celebrate the Ottoman defeat at the gates of Belgrade in 1456.

If the canvas’s upper half is all symmetry and light and transcendence, the lower half is a disquieting mixture of panic, confusion and helplessness in the face of suffering. The 19th-century art historian Jacob Burckhardt remarks that in a lesser painter such a contrast might appear even monstrous.

In fine robes and with a whirligig of gestures, the nine remaining disciples do their desperate earth-bound best to cure a poor demoniac boy portrayed mid-scream. Epilepsy’s devils spew freely from his mouth; his eyes roll east and west. This exorcism appears to have gone wrong and one disciple scrutinises a book as if to find an answer. “Stop! Someone make him stop!” is the viewer’s reaction. The answer, it seems, lies in the incongruously beautiful but disquieting serpentina figure at the picture’s centre. Our gaze, having alighted on what must be western art’s most stunning hairdo, is rerouted via perfect profile and a rhetorical swerve of the woman's shoulder back up the mountain to the scene above. Critics have noted a rather un-Raphaelesque muscularity in the shoulder, closer to Michelangelo’s sybils than Raphael’s sweet madonnas, a clear sign of his rival’s influence, although the story that Michelangelo actually slipped out one night to complete the figure personally must remain apocryphal.

But to return to the story of the canvas itself. After gracing its maker’s funeral, the painting never got to Narbonne after all. Cardinal Giulio kept the original for himself. On Pope Leo’s death, the cardinal, now pope, had it installed in the church of S. Pietro in Montorio. The venue is a fitting one, given Peter’s “witness to majesty”; what's more, the site is believed to be where the saint was crucified. In 1774 a mosaic replica by Stefano Pozzi was made for St Peter’s basilica, rather fortuitous as 20 years later Napoleon carted the original Raphael painting off to Paris.

In 1815 the painting was returned, this time to the Vatican. Meanwhile Raphael’s corpse seems to have gone missing. So much time had passed since his burial that doubts arose whether he had been buried in the Pantheon at all, the archaeologist Carlo Fea in 1816 going so far as to affirm that the artist was probably buried in the S. Maria sopra Minerva church across the road.

Following excavations at the Pantheon, begun on 9 September 1833 under Giuseppe de Fabris, and using Vasari’s Life of Raphael as a guide, the mystery was finally solved after five days' digging: from deep inside the mud emerged a coffin ruined by Roman floodwaters. (Look at the wall of S. Maria sopra Minerva and you can see how frequent they were, along with respective dates and flood-levels.) Raphael’s skeleton, however, was intact.

As celebrated in the sonnet by Rome's 18th-century poet Giuseppe Gioachino Belli: Er corpo aritovato: E’ lui: nun è: ssò cquelle: nun zò quelle:/ E’ Rraffaelle: nun è Rraffaelle…/ E ttutt’er giorno la Ritonna è piena, a second funeral service was ordered and on the evening of 18 October Raphael was reburied in a new pinewood coffin sealed inside a first-century sarcophagus. There he awaits “the Resurrection and the life” which his painting, in its own brilliant way, prefigures.

Martin Bennett

The Transfiguration can be seen today in the Pinacoteca in the Vatican Museums.

This article was published in the September 2015 edition of Wanted in Rome magazine.

General Info

View on Map

Raphael's Transfiguration in the Vatican Museums

VA, Cdad. del Vaticano, 00120 Città del Vaticano, Vatican City