A series of readings and conversations organised by the American Academy in Rome on 9-10 May explores the life and work of the great Latin poet

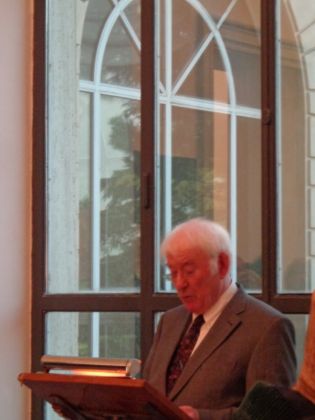

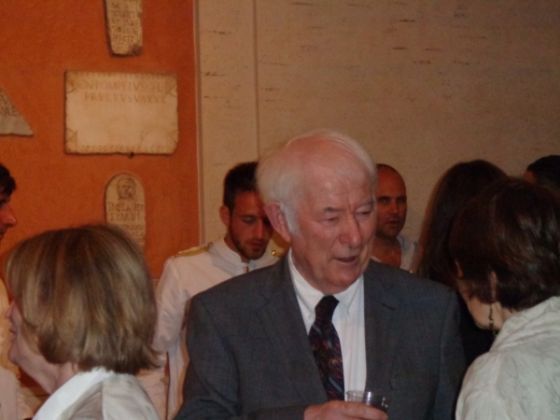

Irish Nobel Laureate poet Seamus Heaney is the William B. Hart Poet-in-Residence at the American Academy in Rome (AAR) for the first three weeks of May. As an AAR Resident, he follows Nobel Laureate poet Derek Walcott from Saint Lucia (2011) and American poet Robert Hass (2012). And Heaney’s beautiful translation of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice (about the poet-singer who rescues his wife from the underworld through the power of his song, only to lose her again) provides the nucleus for a two-day celebration of the life and work of the Roman poet Publius Ovidius Naso, better known as Ovid (43 BC-17/18 AD), in whose long poem called the Metamorphoses this and many other myths are gathered.

In 1994, poets James Lasdun and Michael Hofmann published an anthology entitled After Ovid: New Metamorphoses, including translations or adaptations of myths in Ovid’s best-known work by some 40 English-language poets. Such a many-hands translation of Ovid had an historical precedent: Sir Samuel Garth had published an anthology of translations of the Metamorphoses in 1717 by writers including Dryden, Pope, Addison and Congreve.

One of the contributors to Lasdun and Hofmann’s anthology was Heaney, whose renditions, both of Orpheus and Eurydice and of the myth of the death of Orpheus, established a high-water mark for faithful poetic translation. Others in the anthology included American poet Alice Fulton, whose extraordinarily long poem Give: Apollo and Daphne, a fantasia on the myth of the girl pursued by a god and turned into a laurel tree, represented the opposite end of the spectrum from Heaney’s work: not translation, but a complete reimagining of a myth. James Lasdun himself offered both a faithful translation (of the strange myth of a race of ant-people created to replace those lost to pestilence in The Plague at Aegina) and a reimagining (in a version of the myth of greed, Erisychthon, featuring a ruthless real-estate developer in upstate New York).

The power of Ovid’s definitive collection of Greco-Roman myth to inspire poets has not been limited to contributors to the anthology, however. American poet Frank Bidart’s long poem The Second Hour of the Night is included in a 1997 book entitled Desire, and indeed incorporates Ovid’s myth of Cinyras and Myrrha, about the incestuous passion felt by a daughter for her father, in a meditation about human helplessness in the presence of strong desire. Nor has Ovid’s Metamorphoses failed to inspire literary writers in other genres as well. Italian writer Alessandro Boffa composed a series of Aesop-like fables, entitled in English You’re an Animal, Viskovitz!, in which it is as if the victims of transformation in Ovid’s myths could still speak with their human voices. Anglo-American playwright Timberlake Wertenbaker adapted the bloody myth of Tereus, Philomel and Procne as a play called The Love of the Nightingale (1988), and eminent folklorist and fiction writer Marina Warner based an entire novel, The Leto Bundle, on the myth of Latona and her children Diana and Apollo.

These seven writers are part of a two-day celebration, through literary readings and conversations, of Ovid and his Metamorphoses on 9-10 May that takes place in the historic centre, both at the American Academy in Rome and the Casa delle Letterature. In addition, eminent American Shakespeare scholar Stephen Greenblatt is joined by Renaissance literature scholars Ramie Targoff and Christopher Martin (who is also the editor of the Penguin Books anthology Ovid in English) to discuss the lasting legacy of Ovid in the English Renaissance.

If Ovid’s poem has been perhaps the single most important classical work, in terms of its influence on subsequent western art and literature, the biography of Ovid himself has also had a powerful influence on modern writers. That life offers an example of the rise and fall of the artist so striking that it almost rivals the power of the lives of his mythological characters.

Educated for a career in law and leadership, Ovid instead became one of the most notorious literary figures in Augustan Rome through such works as the Amores (21 BC) and the Art of Love (2 BC). This most cosmopolitan and linguistically gifted of poets was relegated to the outermost edge of civilisation, to Tomis (Constanta, in modern-day Romania), under mysterious circumstances in 8 AD, punished for “a poem and an error”. And from this barbaric outpost his repeated pleas by means of such verse-epistles as the Tristia (9-12 AD) or the Epistulae ex Ponto (13 AD) were ignored, first by Augustus and then by Tiberius, leaving the poet to die in obscurity, far from home.

Fiction writers in particular have loved to speculate about the reasons for Ovid’s banishment and the experience he had in exile, and one of the AAR’s Ovid events will present American fiction writer Jane Alison reading from her novel The Love-Artist, in which Ovid falls in love with a Medea-figure, a barbarian witch, whom he brings to Rome. Readings will also be presented from Australian fiction writer David Malouf’s lyrical novel An Imaginary Life and Austrian fiction writer Christoph Ransmayr’s The Last World. In the latter novel, in fact, the protagonist travels to Tomis and finds a city in which characters bearing the names of those in the Ovidian myths are acting out those myths: so the world of fiction and that of biography become indistinguishable. Ovid himself would have appreciated this blurring between imagination and reality. Both his life and his work have inspired artists for 2,000 years, and will continue to do so.

Karl Kirchwey

Andrew Heiskell Arts Director

American Academy in Rome

“Ovid Transformed: the Poet and the Metamorphoses” is made possible through generous gifts by Mrs. Nancy M. O’Boyle and by Mr and Mrs Charles Price and with the support of the Casa delle Letterature, the British School at Rome and the Keats-Shelley House.

See original version of article in 8 May edition of Wanted in Rome whose cover depicts a detail from the Peruzzi fresco of the myth of Diana and Actaeon.