Rome is full of traces of Pasolini more than four decades after his murder.

By Martin Bennett

Now you glimpse him now you don’t: Pasolini is still a presence 40 years after his death. He ghosts the Pigneto district rather like the shade of Pessoa haunts Wim Wenders’ film, Lisbon Story. In Via Fanfulla da Lodi, a “poor, humble little-known street”, the poet, novelist, film-maker, polemicist and ultimate polymath pops up time and again in some of Rome’s best street art.

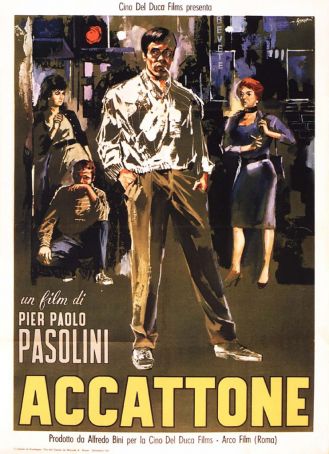

Cast your gaze back and upwards as you pass number 41. There, courtesy of painter Mauro Pallotta (a.k.a. Maupal), Pasolini – illustrating his own dictum “The eye alone is aware of beauty” – keeps giant-eyed watch over the road he immortalised in the film Accattone. Up on the house opposite stretches the mural/giant icon of the young Madonna as represented by Margherita Caruso in his Gospel according to Saint Matthew. (The older Mary was played by his mother.)

At the next corner in Bar Necci (number 68) a series of photographs shows Pasolini in full directorial flow. Light meter on legs, in one photo there he is, taking the measure of the street’s blaze and shadow, patrolling its cinematically ideal north south-axis for the perfect shot.

Necci's bar being rather upmarket, Accattone used the improvised, more rudimentary Vini e Olii a few doors down (number 50), more in line with the hard-up, desperate lives of the so-called ragazzi di vita the film portrays. Granular majesty is how Pasolini, a poet before a film-maker, describes the setting. Another Vini e Olii (Vecchia Cantina, Via Pigneto 118) boasts a snap of Pasolini alongside a young and electrifying Bernardo Bertolucci.

Accattone came out in 1961, but Pasolini’s introduction to Rome – stupenda e misera città – was ten years earlier. After a spell in the Jewish ghetto area (Portico d’Ottavia), he settled in Ponte Mammolo, in the shadow of Rebibbia prison. To cite his poem Il pianto della Scavatrice / The digger’s lament:

“The inland plain where a metropolis vanishes / into hovels: in this world / over which with row upon row / of small barred windows, the penitentiary / alone holds sway, a cubist spectre / looming amidst the yellowish smog – / stunted houses and what once / were fields cowering below.”

The scene features in a Cartier-Bresson photograph: some ragazzi perch on a seeming precipice of shadow while the newly-built prison looms behind. HCB had astutely co-opted Pasolini as guide.

There in the borgate he lived “poor as a Colosseum cat / in an outer suburb with no landmarks / but lime and filth, neither countryside / nor city…” 1

These days asphalt and concrete have replaced the “hovels white with dust / curtains for doors, not a fitting in sight.” Yet for anybody who has lived in Via Tiburtina’s farthest reaches, the verse “daily packed tight / inside a rattling bus: / and each trip out, each trip back / was a Calvary of hassle and sweat,” resonates as if written yesterday. 2

It was while living in the same run-down area that Pasolini describes his artistic / political awakening:

“Something within me took root, / at once mine yet not mine, / nourished by the happiness of one / who loves, even if he’s not loved back.” He then continues, “I was at the world’s hub, of all places / here amidst this sad shanty, / these yellow meadows rubbed bald / by the relentless wind.” 3

The experience is all the more convincing for being so unlikely:

“Everything was / about to become clear - was, yes, / clear! This ghetto unshielded from the wind, / not Roman, not southern, / not even strictly working class, / it was life as it is lived: / life, and light of life, full to bursting, / not yet pigeonholed ‘proletarian’.” 4

Life as it is lived was also inspiration for three novels. To quote Italian critic and novelist Walter Siti: “Pasolini wove a fabric where every smallest biographical episode, every wavering doubt, has no rest until transformed into a poem or story.”

Pasolini’s arrival in Rome in 1950 was anything but promising. “I fled with my mother, a suitcase and a handful of joys proven false,” he describes the fall-out after a scandal arising out of his sexual orientation back in his native Friuli, from which, actually, he was to be officially exonerated. Or again, “I live as might someone condemned to death…that thought nagging at me, the wretchedness of unemployment, my mother reduced to a servant…”

With private lessons and proofreading, he eked out a living. And continued to write, walking the city like a modern Dickens or Baudelaire, as referenced in his letter to poet Elio Accrocca:“…I leave home and start to stroll, almost always around 2am….I devour, devour. How it will end I don’t know…”

Pasolini’s delight in low-life was coupled with soon-to-become cinematic powers of observation: “About faces I was never wrong.” One film critic concurs: “Each of his faces is worth a book.” In this respect he’s often twinned with Caravaggio. No surprise given that the great Caravaggio expert, Roberto Longhi, was Pasolini’s one-time mentor back in Bologna University.

Through his friendship with Sergio Citi (“living Roman lexicon”, brother of Franco, star of Accattone) Pasolini internalised just such a language, being eventually appointed Fellini’s so-called Romanesco language consultant for Notti in Cabiria, receiving a new Fiat 500 for his pains.

Also a master of the city’s topography, in his work he criss-crosses the city. Viale Marconi; Trastevere whose Piazza Egidio has one of his poems on a bronze plaque; Villa Doria Pamphilj, Testaccio, Gianicolo: all are brought to life. So also Via Casalina in the story La Mignotta which would develop into the film Mamma Roma, set partly in Ostia’s Idro Scalo where, by cruel irony, Pasolini would meet his death.

An earlier poem in Dante-esque terza rima – Gramsci’s Ashes – is set in Rome’s non-Catholic/foreigners’ cemetery. Radiating outward, it is a meditation on shared “outsider-dom.”

However things got better. For 20,000 lira per month Pasolini found a job in a Ciampino school; his ex-pupils, some turning into writers in their own right, affirm he was the most inspirational of teachers. He also befriended the era’s literary heavyweights – Attilio Bertolucci, Giorgio Caproni, Alberto Moravia.

“It seemed to me that Italy, / its description and its destiny / depended on what I wrote / in these verses steeped in immediate reality / no longer nostalgic, earned by my own sweat,” Pasolini claimed. Critics after his death agree. “A life of commitment”, says Fernanda Pivano. “…putting his innards on a plate,” to borrow a splendid phrase from Walter Siti, also editor of the three-volume edition of Pasolini’s poems.

The ragazzi di vita may have passed on or are deep into middle age. One has opened a mini-museum at number 112, Via Pigneto’s “British Corner”, and will swap memories for a cup of tea. Yet Pasolini’s critique – against the grain, fiercely anti-institutional, remains as valid as ever, urgent even.

SIDE NOTES

For details of Pasolini murals that appeared around Rome during 2015 see Wanted in Rome article.

1-4. Translations by Martin Bennett, from Pasolini's poem Il pianto della Scavatrice, part of the collection Le ceneri di Gramsci (1957). Bennett's translation originally appeared in Modern Poetry in Translation magazine, first published by King's College, London, in 1999.

This article was published in the December 2015 edition of Wanted in Rome magazine.