The British Spies Who Helped Free Italy: The Secret Missions of Cecil Richard Mallaby and the SOE.

During the Second World War, while armies clashed across Europe, a quieter, more covert battle was being fought behind enemy lines. One of the most remarkable and little-known figures of that shadow war was Cecil Richard Mallaby, a British officer working for the Special Operations Executive (SOE) — the secret organisation created by Winston Churchill to “set Europe ablaze” through sabotage, resistance coordination and espionage.

In the summer of 1943, Mallaby undertook a mission that would play a critical role in shifting Italy’s position in the war and opening the door to the Allied liberation of the country. His operations, shrouded in secrecy for decades, remain one of the most fascinating examples of Allied intelligence work in wartime Italy.

A Lone Agent Behind Enemy Lines

By mid-1943, Italy was on the brink of collapse. Mussolini had been deposed on 25 July, and Marshal Pietro Badoglio had taken control of the government. While the new regime began secret negotiations with the Allies, the military situation remained tense. The Allies had landed in Sicily and were pushing north. With German forces still entrenched, the Italian government needed to switch sides — but without triggering a German retaliation before the armistice could be implemented.

Enter Cecil Richard Mallaby, fluent in Italian and trained in covert operations. On 31 August 1943, he parachuted alone into the hills above Lake Como. His mission, code-named “Operation Olaf,” was to establish secure contact with both the new Italian authorities and the partisans, and to transmit critical information to the Allied command in Algiers.

Within hours of landing near the village of Civenna, however, Mallaby was arrested by Italian carabinieri. He was carrying a fake identity, a miniature radio disguised as a shaving brush, photographic negatives hidden inside battery cases and encrypted documents. Despite being interrogated and likely tortured, Mallaby did not reveal his mission. And thanks to the chaotic state of the Italian military and shifting political alliances, he was released soon afterwards — a stroke of luck that allowed him to resume his mission.

Facilitating the Armistice

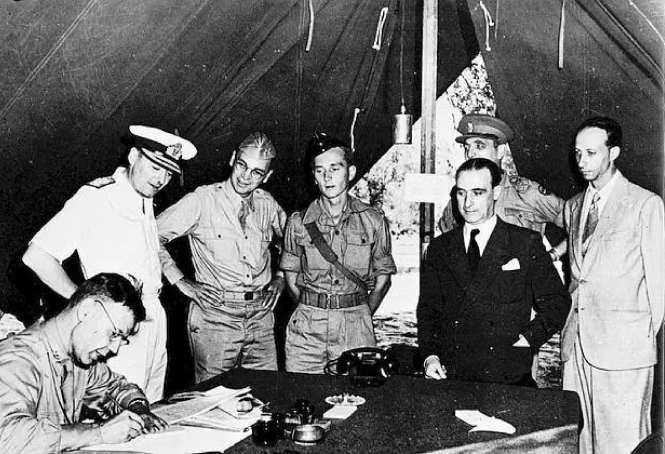

Following his release, Mallaby managed to re-establish radio contact with Allied forces. From this point, he played a vital role as a courier and coordinator of secret communications between the Italian government and the Allied command in North Africa. He transmitted information that helped confirm Italy’s willingness to surrender and contributed to the logistics of the Armistice of Cassibile, signed on 3 September 1943 and publicly announced on 8 September.

At the time, Italy was still considered an enemy by the Allies, and any open declaration of intent could have triggered brutal German retaliation — as would indeed happen in the days following the armistice. Mallaby’s actions were instrumental in building the fragile bridge of trust necessary to facilitate Italy’s exit from the Axis alliance.

Operation Sunrise and the Endgame

Mallaby returned to Italy in 1945 during Operation Sunrise, a secret diplomatic initiative between the Allies and Nazi representatives to negotiate the early surrender of German forces in Italy. Coordinated by Allen Dulles, the OSS station chief in Bern (and future CIA director), the operation aimed to shorten the war in Italy and avoid unnecessary destruction.

While the operation was led at the highest political and military levels, Mallaby was once again active in the network of communications, helping maintain secure channels between negotiators and local resistance forces. The talks ultimately led to the surrender of German troops in northern Italy on 2 May 1945, days before the official end of the war in Europe.

A Shared Mission: The Role of Christine Northcote Mallaby

Behind Cecil Richard Mallaby’s daring fieldwork was a partner equally involved in the war effort: his wife, Christine Northcote Mallaby. She worked as a cryptographer for the SOE, and their relationship itself began through Morse code during training. Christine’s expertise in deciphering and encoding messages formed part of the invisible backbone that supported missions like Richard’s.

Theirs was not just a marriage, but a partnership in service of Allied intelligence — a story of love, trust and mutual risk under extraordinary circumstances.

Recognition, Legacy — and a Dash of 007

For his bravery and service, Cecil Richard Mallaby was awarded the Military Cross, a high British military honour. Yet, like many SOE operations, his mission remained classified for decades, and public recognition came only much later.

In recent years, local communities in Italy — including the Tuscan town of Asciano, where Mallaby found refuge after the war — have begun honouring his memory with public ceremonies and posthumous medals.

His story offers a powerful reminder of the unsung international actors who helped shape Italy’s liberation — not through grand battles, but through silent acts of courage, risk and loyalty.

And there’s one more twist: according to some accounts, Ian Fleming — the creator of James Bond — may have drawn inspiration from Mallaby’s exploits when imagining 007. Fluent in languages, master of disguise, fearless under pressure, and romantically linked to a fellow agent? The resemblance is more than passing.

Spies, Radios, and Resistance

Mallaby’s legacy lies in his unique combination of linguistic skill, technical training, and moral clarity. He operated with no backup, no immediate allies, and only his equipment, his instincts, and his mission. In doing so, he became a vital link between the collapsing Italian regime and the Allied forces that would soon enter Rome.

His story is a testament to how the tide of history can be turned not just by armies, but by individuals willing to act — quietly, cleverly and bravely — when it matters most.