Rome as muse for English-language poets

Over the centuries Rome has inspired numerous English-language poets.

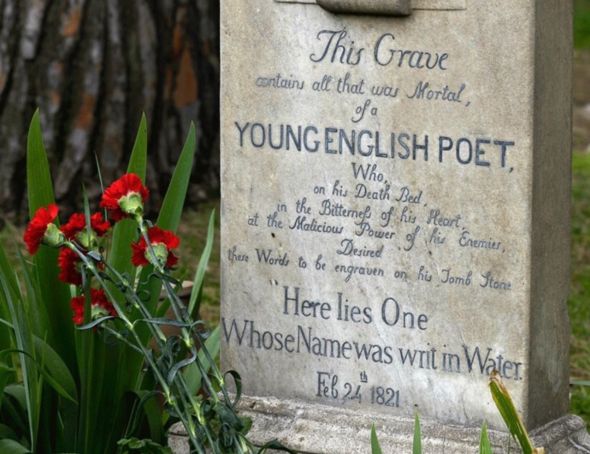

Lovers of English poetry must often wonder what Keats would have made of Rome had he lived. But he died in terrible agony only three months after his arrival in November 1820 and hardly ventured much beyond Piazza di Spagna where he was lodging (now the Keats-Shelley House at no 26).

We can only speculate what he might have made of the ruins, the light, the paintings, the people that so inspired others down the centuries, from Shakespeare to Brodsky.

Rome’s link with poetry in English, however, remains an intimate one. As Ezra Pound praises Latin poet Sextus Propertius for bringing “the Greek dance to Italy”, so literary historians credit Sir Thomas Wyatt, courtier to Henry VIII, with bringing the Petrarchan sonnet to England, a spin-off of a 1527 diplomatic mission to Rome. Indeed, Wyatt, poet and aspiring lover, adopts and adapts Petrarch’s sonnet CXC to bewail, vis-à-vis his “deer”/dear Anne Boleyn, his own predicament:

“There is written her fair neck round about

Noli mi tangere for Caesar’s I am:

And wild to hold, though I seem tame.”

The same “Caesar”/Henry VIII would later imprison Wyatt in the Tower of London for treason, though, unlike poor Anne, he was spared execution through a last-minute reprieve. The sonnet form, after further adjustments by Wyatt’s follower and fellow sonneteer Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, was ready – complete with iambic pentameter and closing couplet – to be handed on to Shakespeare.

Shakespeare's Rome

Rome, of course, appears – and how! – in the plays, such as Titus Andronicus, Julius Caesar, Coriolanus, and Antony and Cleopatra, with an authenticity to make Sicilian professor Martino Iuvara put the case that the Bard was Italian born and bred.

Baroque sensibility

Three decades after Shakespeare, the Catholic exile Richard Crashaw certainly did stay in Rome.

The Oxford Anthology of English Literature cites the “controlled frenzy” of Crashaw's 1648 poem, The Flaming Heart, celebrating St Theresa, a fitting match for Bernini’s statue in S. Maria della Vittoria sculpted in the same period. The 20th-century literary critic Douglas Bush called Crashaw “the one conspicuous incarnation of Baroque sensibility”, of a particularly English variety, via of course Italy.

Rome’s Baroque is later reprised in Robert Browning’s The Bishop Orders his Tomb at Saint Praxed’s Church. Thinking of his former mistress, a bishop from his deathbed addresses his “nephews”/sons, his envisaged tomb being an exercise less in spirituality than in ecclesiastical one-upmanship. The “nephews” evidently failed to take their dying father at his word to build the tomb. Visit St Prassede’s – “the church for peace” – and you’ll look for the tomb in vain. The artefact is a figment of Browning’s sumptuous, and somewhat mischievous, imagination.

Unlike the still viewable Baroque Wall Fountain in Villa Sciarra, described with flowing intricacy by 20th-century American poet, Richard Wilbur. “It spills/ In threads from the scalloped faun ménage….// Happy in all that ragged, loose/ Collapse of water, its effortless descent/And flatteries of spray, / The stocky god upholds the shell with ease…’ And so on for a dozen delicately sculpted quatrains to do an old Baroque master proud.

Anyone lucky enough to study A-Level English in the late 1960s will recall as set text Thom Gunn’s In Santa Maria del Popolo: “Waiting for when the sun an hour or less / Conveniently oblique makes visible / The painting on one wall of the recess”.

Caravaggio

State-of-the-art lighting now makes any wait to see Caravaggio's masterpiece unnecessary. Gunn’s existential interpretation of the outstretched arms of Saul becoming Paul still sounds bleakly impressive: “the large gesture of solitary man, / Resisting, by embracing nothing.” It surely falls short, however, of Caravaggio’s intention. For balance here’s a translation of art critic Vittorio Sgarbi’s prose: “The fall is the miracle. Pride has been humiliated and the man is at the mercy of the animal that could crush him at any moment. Yet this humiliation is the beginning of redemption.”

Byron’s “Manfred” waxes duly reverential: “I stood within the Coliseum wall, / Mid the chief relics of almighty Rome; / The trees which grew along the broken arches / Were dark in the blue midnight, and the stars / Shone through the rents of ruin.” But the same poet’s Childe Harold can express a less conventional empathy for the monument’s victims: “I saw before me a gladiator lie…. / butchered to make a Roman holiday.”

Romantic raptures

Meanwhile English poet Arthur Hugh Clough, visiting Rome during the 1848/49 uprising of the Roman Republic, complains in Amours de Voyage: “Rome disappoints me much…/ Rubbishy seems the word that most exactly would suit it”, sharpening the dose with, “Brickwork I found thee, and marble I left thee, their Emperor vaunted; / Marble I thought thee and brick I find thee, the Tourist my answer…” No romantic raptures here, though another section fizzles with the immediacy of a stop-press dispatch: “a National Guard close by me…. / Broke his sword with slashing a broad hat covered in dust – and / Passing away from the place with Murray under my arm, and / Stooping, I saw through the legs of the people the legs of a body…’

Rome's ruins

Ruins mean different things to different people. Archaeology and immediate autobiography (the birth of a daughter) converge in the poem To the Roman Forum by New York poet Kennet Koch: “I went down and sat and looked at the ruins of you / I gazed at them, gleaming in the half-night / And o my, My goodness, a child, a wife…// I thought I’d look at some very old great things / To match up with this new one...”

Rome’s ruins and more ruins, but also and above all its light. Such that “On the threshold of heaven, the figures of the street / Become figures of heaven, the majestic movement / Of men growing small in the distances of space”, from the Wallace Stevens poem To an Old Philosopher in Rome. In the poem Stevens attributes the perception to his former tutor George Santayana, whose last decade was spent on the Coelian hill, lodging in the convent of the Blue Nuns of the Little Company of Mary near the S. Stefano Rotondo church.

If, around dusk or dawn, you happen to be in Rome’s Monti district, gaze down at the sun bouncing off the sanpietrini of Via Panisperna as it undulates toward Trajan’s Markets and one can replicate Stevens' experience of growing small in distant spaces, or, by gazing upwards: “How easily the blown banners turn to wings.”

Elegies to Rome

Stevens' celestial possible re-emerges in the following extract from Joseph Brodsky's Roman Elegies (1981), written during the Nobel Laureate’s stay at the American Academy up on the Gianicolo: To translate, making allowances for rhyme, from an Italian translation of the original Russian: “I have been to Rome. I was drowned in light, / The way only a splinter can dream about; / A drachma of gold’s been placed across my sight. / It’s enough to see me through the longest night.”

This an echo of “Go thou to Rome…” from Shelley’s Adonais, his elegy to John Keats buried in Rome’s Non-Catholic Cemetery. The Brodsky piece mirrors the lines three stanzas later: “The One remains, the many change and pass; / Heaven’s light forever shines, Earth’s shadows fly; / Life, like a dome of many-coloured glass, / Stains the white radiance of Eternity…”

By Martin Bennett