By Dana English.

A hidden garden at the monastery of S. Gregorio al Celio is a tangible symbol of ecumenism in Rome.

The ancient foundations of the Monastery of S. Gregorio al Celio have stood for over 1,500 years in the same place, at the foot of the Clivus Scauri, the Roman road that led to Porta Celimontana from the Circus Maximus and the imperial residences on the Palatine hill opposite.

It was in this villa in this neighbourhood, having become the favoured place of aristocratic residences geographically close to the seat of power, that Gregory was born into a wealthy patrician Roman family with close connections to the Church. His great-great-grandfather was Pope Felix III. His father, Gordianus, was a senator and prefect of the city of Rome. The highly-educated Gregory also became prefect at the early age of 33.

On the death of his father, however, Gregory decided to convert his family’s villa into a monastery dedicated to St Andrew and embrace a life of contemplation as a monk. The times demanded his talents in the arenas of both church and state, however; Pope Pelagius II sent him as an ambassador to Constantinople for the next seven years.

Pope Gregory

Although desiring only to return to the peace of his monastery, Gregory was not to enjoy the monastic quiet for long: he was named pope in 590 (on his part, reluctantly). In this troubled period in Rome's history, the papacy emerged as the only possible source of authority to hold the disintegrating system of governance together. His capable administration saved the citizens of Rome from starvation on more than one occasion.

A teacher and reformer rather than a theologian, Gregory is perhaps most famous for having sent Augustine and 40 monks to re-evangelise the British in the year 597, and extend the reach of the Gospel to the now-pagan north of Europe.

It is at this historic site of connection between Rome and England that the Archbishop of Canterbury celebrates vespers with the Pope when he visits. On 5 October last year, Justin Welby and Francis commissioned and sent 40 pairs of Roman Catholic and Anglican bishops to engage in mission together all over the world to mark the 50th anniversary of the ecumenical work of the Anglican Centre in Rome.

Hidden garden

The most visible, tangible sign of ecumenism in Rome, however, is a hidden garden on the same site, the monastery of S. Gregorio al Celio. Although the Camaldolese branch of the Benedictine order has occupied this site for over a millennium, the dwindling number of monks in recent decades had reduced the monastery’s once-flourishing garden to an abandoned patch of dirt, weeds and unpruned fruit trees.

Five years ago, in June 2012, an Anglican priest and four Anglican ordinands held their pre-ordination retreat at S. Gregorio, and on their first evening there they placed their chairs in a circle on the edge of the garden. As the sun set, they shared their stories of what had brought them to that place. Each person looked out at the garden and expressed the same thought, that it was such a pity that it was so neglected and overgrown. The retreat ended; all were ordained; each went away on vacation; each began his or her new work. One of those who had been newly ordained, Verna Veritie, had just begun her ministry as a deacon in the place she was most needed, Athens, when she was killed in an accident there.

English-speaking churches

I was one of the other ordinands from that evening in the garden and decided to try to restore it in her memory. As assistant curate and then assistant chaplain at All Saints’ Anglican Church in Rome, I gathered members from the English-speaking churches in Rome – Swedish and German Lutheran, Methodist, Anglican, Presbyterian, Roman Catholic, members of the Franciscan order – to clear the space and begin to re-plant the site.

Beth Blosser, a member of All Saints’ and a landscape gardener then employed in work on the secret gardens of Villa Borghese, drew up a beautiful design in keeping with the history of the ancient site.

Despite obstacles of all sorts, most notably the infamous bureaucracy of Rome, we managed to raise over €20,000. We toured people through the developing garden during all its various stages. We bought plants and hired contractors for the work the volunteers could not do: to turn up the earth and sow the grass seed, relocate the lighting, install the watering system, create the crushed marble paths, prune the trees, install an iron pergola and install six travertine marble benches. And place the brass plaques on the benches and the wall of the church, commemorating 20 May 2017 as the day of blessing and dedication of the Ecumenical Garden in Rome.

Work in progress

No garden is ever “finished”. The Ecumenical Garden still awaits smooth, flat, white stones to be laid in a spiral pattern as a labyrinth for meditation. A fountain will replace the antique Corinthian capital found on the site (with a solar panel to run the circulating water). Additional plants are needed to fill in the kitchen garden and the borders. Scaffolding is required to place grates over holes in the masonry of the church to keep out the pigeons, and install spikes to keep the roof edges clear. This wish list may require another €2,000 or €3,000. And especially during the second half of July and throughout August, volunteers will continue to be needed to combat the weeds and check for additional watering that might be necessary.

Only two of the original Camaldolese community were present at the dedication: Brother Innocenzo and Brother Bonifacio (who will be 90 in November). Six seminarians and monks from other places including India, China, and Brazil, with half a dozen other guests, make up the present resident community. The mother house of the Camaldoli in Umbria has also sent some of its monks to live at S. Gregorio.

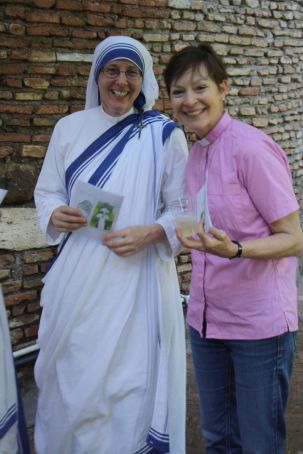

An additional community occupies the former chicken coop of the monastery: the Missionaries of Charity, Mother Teresa’s order. They preserve her cell as it was when she used to visit Rome; they are glad to show it to those who come (except on Thursdays). Twenty energetic and compassionate sisters care for 67 persons in another part of the complex, next to the garden, providing shelter, food and care to a group of men for whom the criteria are that they are over 55 and very ill. The sisters also operate a hostel near Termini for younger men who have just arrived in Rome: they give a shower, clothing, food and a bed to refugees from all parts of the world, for a maximum of three weeks. The sisters enjoy the garden as they cross it to transport deliveries of food that are unloaded in the lane behind the monastery.

A group from a Bible Study at FAO, across the street, meets in the garden once a month to enjoy picnic lunches on the green lawn amid the orange trees. Members of nearby St Stephen’s School garden club help on Saturday mornings, trimming and weeding throughout the year. The Notre Dame University programme and other college groups from the United States have corresponded to set up special work sessions in the garden as a form of service, complementing their academic programmes.

Looking ahead

A comprehensive plan for the use of the garden is being drawn up. It will include the celebration of wedding blessings there and retreats for small groups (overnight or weekend retreats could be accommodated; many of the 12 guest rooms overlook the garden). A register will list the names of those who have contributed to the garden through their time, labour or donations: all those who have contributed in some way will be able to use the garden for times of quiet and reflection and prayer.

As the roses and grapevine climb ever higher to cover the pergola, as the ivy fans out and fills in to conceal the fence covering, as the plants that border the garden cluster and grow denser in their colour and variety, the garden will become an ever more welcoming place for those who seek a green place in the middle of the city, in the spirit of Gregory the Great’s monastery that began its life on that very place in the sixth century AD.

To enquire about a visit to the garden, or to make a contribution to its ongoing life, contact the Rev’d Dana English at dlenglish@aya.yale.edu. The garden's website is ecumenicalgarden.blogspot.it.

This article was published in the July 2017 edition of Wanted in Rome magazine.