Artists have portrayed Rome's Non-Catholic Cemetery for three centuries.

Nicholas Stanley-Price

In 1872-73 the English artist Walter Crane spent 18 months on his honeymoon in Italy, most of it in Rome. Influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones, he had already started to illustrate children’s books, the talent for which he is perhaps best known today. During his long stay here with his bride Mary, he spent many days sketching in the open air. Among the commissions he received while in Rome were two from George Howard, a friend and patron of Burne-Jones and himself an amateur artist, for views of the graves of John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley in the Protestant Cemetery.

Romantic poets

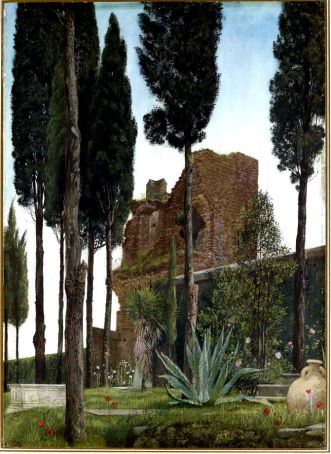

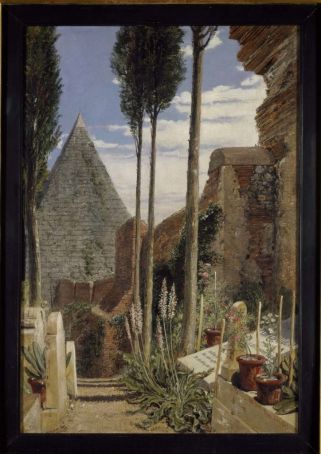

Those who visit the graves of the two Romantic poets today know how dissimilar they are. Even if lacking his name, as the poet had requested, the headstone of Keats is easy to find. But many visitors fail to locate Shelley’s grave at the first attempt. It is a simple horizontal ledger-stone, situated at the foot of a tower of the old city wall in what Edward Trelawny, when selecting it in 1823, had called “the only interesting spot”. Even if not visually striking, it is nonetheless evocative for lovers of Shelley’s poetry. Crane’s watercolour captures delightfully the peaceful atmosphere of the setting, the tower of the Aurelian wall and the cypress trees planted by Trelawny, but the grave-slab can hardly be seen. Soon after the Cranes had left for England, by chance William Bell Scott also painted the poets’ graves. For Shelley’s he chose a much closer viewpoint and allowed himself to elevate the slab in order to show its inscription.

Exhibition at Casa di Goethe

All four paintings by Crane and Scott are in the collections of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford but they will be on display in an exhibition opening this month at the Casa di Goethe in Rome, At the foot of the Pyramid: 300 years of the cemetery for foreigners in Rome. The exhibition, which runs from 22 September to 13 November, presents a short historical survey of how visual artists have responded to the burial-ground where, for 300 years, non-Catholic foreigners have been laid to rest. Many of the loans have not been shown before in Rome and never together in one venue. All but one of the 43 paintings, drawings and prints date from the 18th and 19th centuries. The exception is strikingly different, an oil painting of his uncle’s grave made by Edvard Munch during his visit to the city in 1927.

Most artists who painted or drew this beautiful spot selected it primarily for aesthetic reasons. But some, such as Munch, had a personal motivation, and others had attended the funerals of fellow artists there. Several works in the exhibition were commissions from relatives wishing to have a visual souvenir of the grave of the husband, wife or child who had died in a far-off land. Paintings of the graves of Keats and Shelley were often made either on request or speculatively for sale to admirers of the poets.

Pyramid of Caius Cestius

But what if, as in the case of Shelley’s grave, it was difficult to do justice to it in a painting? It is here that the pyramid of Caius Cestius, now looking splendid after its recent restoration, played a symbolic role. In this exhibition devoted to the cemetery “at the foot of the pyramid”, Cestius’s tomb is visible in all but eight of the works on show. It acts as a more visible memorial for those Protestant, Orthodox, Jewish and other graves that were marked only by a humble stone or a low earth mound. The American novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne had exactly this thought when observing that the burial-ground lay “so close to the pyramid of Caius Cestius that the latter may serve as a general monument to the dead.”

The event is also an opportunity to challenge assertions often made about discrimination against the “heretic” Protestants. For the first time in one place, it shows three of the six known depictions of funeral ceremonies held at the foot of the Pyramid. From Geneva comes a drawing by the Swiss artist Jacques Sablet (whose famous painting Élégie romaine will also be on show) and from Stockholm another recording the burial of the Swedish artist Jonas Åkerström in 1795. These join the Museo di Roma’s engraving of Bartolomeo Pinelli’s fine watercolour of a similar funeral scene – the original in Weimar in Germany is unfortunately not allowed to travel. The evidence overall suggests that, far from having to be held in secret as often claimed, these funerals were well-attended by Romans and foreigners alike, and were held with all due permissions from the city authorities.

Advent of photography

Why is Munch the only artist represented from after 1900? Although not true of Rome as a whole nor of the Pyramid specifically, it seems that the invention of photography led to the cemetery becoming a less popular subject for artists in pencil and paint. Many of the early photographers in Rome, such as Giacomo Caneva, Gioacchino Altobelli and Robert Macpherson, had trained as painters but switched to the new technique. Their cameras captured the “classic views” of the cemetery, with the Pyramid in the background that had hitherto been the subject of widely disseminated prints. Their photographs, later mass-reproduced as popular postcards, led to a diminished demand for paintings and drawings. So it is not a recent phenomenon that the camera has prevailed as the principal means of creating visual souvenirs of the burial ground and of individual graves.

Cemetery and foreigners

For 300 years the cemetery has been an inescapable element of the foreigner’s experience in Rome, not least for those numerous artists who settled in the city. Some of them died young of illness, others peacefully in their adopted home. The graves of over 100 recognised artists from some 20 countries can be found there.

The exhibition is a rare opportunity to see how they were inspired by the place that Henry James, writing to his mother, called “that divine little protestant Cemetery where Shelley & Keats lie buried – a place most lovely & solemn & exquisitely full of the traditional Roman quality – with the vast grey pyramid inserted into the sky on one side & the dark cold cypresses on the other & the light bursting out between them & the whole surrounding landscape swooning away for very picturesqueness.”

SIDE NOTES

EXHIBITION

At the foot of the Pyramid: 300 years of the cemetery for foreigners in Rome, (22 Sept–13 Nov), organised by the Non-Catholic Cemetery in Rome and the Casa di Goethe held at the Casa di Goethe, Via del Corso 18 (Piazza del Popolo) Rome, and curated by the author. Catalogue available in English, Italian and German editions.

THE CEMETERY IN HISTORY

The first non-Catholic known to have been buried on this spot was William Arthur from Edinburgh who died in 1716. Most early graves are of Protestant members of the Stuart court in exile from Britain which arrived in Rome in 1719. Others are of young men on the Grand Tour or visiting artists who fell ill while in the city. After 100 years of use of the Old Cemetery, the papal authorities stopped further burials there and opened a new area nearby (the “New Cemetery”), where the main entrance is today. Extensions were added in the 1850s and the 1890s. Foreign diplomats posted to Rome have always been responsible for the burial-ground, with Prussia, succeeded by Germany in 1870, playing the leading role. Since the 1920s it has come under a board of 14 ambassadors, increased in 2014 to 15 with the accession of Ireland. The president of the board is currently the ambassador of Canada to Italy, Peter McGovern.

THE CEMETERY TODAY

To be buried there today you must be non-Catholic, non-Italian and resident in Italy. However, the Italian Catholic spouses and children of qualifying foreigners also have the right. Since 2008 the director has been Amanda Thursfield, who manages a very small staff and a large group of devoted volunteers. Donations towards the costs of maintaining this private cemetery can be made on the spot by visitors or through its website. Via Caio Cestio 6. Mon-Sat 09.00-17.00, Sun 09.00-13.00.

NICHOLAS STANLEY-PRICE

Nicholas Stanley-Price is a former director-general of ICCROM in Rome and is considered one of the foremost experts on archaeological site conservation worldwide. For further reading on the Non-Catholic Cemetery see his book The Non-Catholic Cemetery in Rome. Its history, its people and its survival for 300 years, 2014 (also in Italian and, from September, in German).