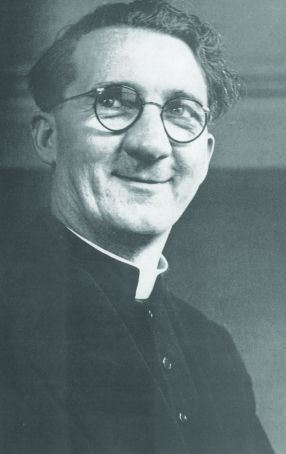

Monsignor Hugh O'Flaherty: Rome's Oskar Schindler

O’Flaherty saved the lives of over 6,000 escapees in Rome during world war two.

On 8 May 2016 a plaque was unveiled at the Vatican's Collegium Teutonicum to honour the Irish priest Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty (1898-1964) for his work in rescuing Allied soldiers and Jews during world war two. After it was blessed by the rector of the college, two laurel wreaths were placed at the foot of the plaque on behalf of the Irish and British embassies to the Holy See.

Ordained to the priesthood in 1925, following his studies in Rome, O'Flaherty was involved in a number of diplomatic postings in the early 1930s. In 1939 he was appointed to the Holy office, now the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and spent the next 20 years living at the Collegium Teutonicum.

Prisoner of war camps

On Italy’s entry into world war two in 1941, O’Flaherty accompanied the papal nuncio to Italy in visiting prisoner of war (POW) camps in the north of Italy where thousands of Allied prisoners were confined. Unimpressed with the nuncio’s leisurely approach to his mission, O’Flaherty became much more involved. Travelling back to Rome from the north of Italy every night, he had the names of prisoners broadcast over Vatican Radio to reassure their loved ones at home.

No respecter of red tape, he did not endear himself to the Italian military authorities and was responsible for the removal of two commandants at Piacenza and Modena, over their poor treatment of prisoners. Eventually complaints were made to the Vatican about this meddlesome priest, and O'Flaherty had to step down from his position and return to his office job in the Holy Office. The Allied invasion of north Africa in 1942 meant this time there were Italian POWs to be traced and helped, with their families seeking help from the Vatican.

Allies and Fascists

This invaluable experience in helping POWs was to stand O’Flaherty in good stead. In July 1943 the Allies landed in Italy and the war started coming closer to Rome. The Fascists increased their searches in the capital for prominent Jews and well-known anti-Fascists in the aristocracy. Whenever some of these needed to go into hiding, he would direct them to reliable friends or to convents and monasteries. But this proved insufficient.

The Irish monsignor hit on using his own residence, the Collegium Teutonicum, which had Vatican immunity. One of his first guests was Princess Ninì Pallavicini whose palace was raided when an illegal radio she had was tracked down by the Fascists. O’Flaherty found her accommodation in the nun’s quarters in the Collegium Teutonicum where she proved an invaluable assistance because of her skills in forging top-class identity documents.

Council of Four

In July 1943 there were 74,000 known British POWs in Italy. Escapees tended to make their way to Rome and after the Italian surrender on 8 September, the trickle turned into a flood. Money, food and premises needed to be found urgently and it became much more dangerous after the German occupation of Rome on 11 September. O’Flaherty pointed out the gravity of the situation to Sir D’Arcy Osborne, British minister to the Holy See, resident inside the Vatican Walls at Casa S. Marta, where Pope Francis now lives, since the beginning of the war. Initially non-committal, Osborne replied that he could not compromise his own position nor the neutrality of the Vatican.

But the monsignor insisted, saying that men would get sick and die in the mountains. Osborne relented, promising help from his own personal funds, and suggested that O’Flaherty talk to his butler John May. He added that he did not want to know any details so as not to compromise diplomatic relations with the Holy See. May recruited Count Sarsfield Salazar from the Swiss legation to set up the Council of Three which later became the Council of Four when British Major Sam Derry escaped to Rome. May was insistent that the team helping escapers needed a permanent organisation, that the operation was far too big for one man on his own. It was thus that the Rome Escape Line came into being.

O'Flaherty's motivation

No Anglophile, given his personal experience of the Black and Tans during the Irish war of Independence, O’Flaherty explained his motivation to Derry in 1943: “When this war started I used to listen to the broadcasts from both sides. All propaganda, of course, and both making the same terrible charges against the other. I frankly didn’t know which side to believe – until they started rounding up the Jews in Rome. They treated them like beasts, making old men and respectable women get down on their knees and scrub the roads. You know the sort of thing that happened after that; it got worse and worse, and I knew then which side I had to believe.”

Safe houses

O’Flaherty found safe houses all over Rome. One of his most generous helpers was Henriette Chevalier, a 42-year-old Maltese widow with eight children who lived in a small apartment on Via dell’Impero (today Via dei Fori Imperiali). When he rented an apartment on Via Firenze, adjacent to the hotel that the Gestapo had commandeered as their Rome headquarters, he dismissed his friends’ concerns with the remark: “Faith, they’ll never think of looking under their noses.”

Another valued accomplice was Delia Murphy, wife of the Irish minister to the Vatican. She often used the legation’s diplomatic-registered car to transport escaping prisoners through enemy checkpoints, well aware of the implications for Irish neutrality had she been caught. Her beautiful 19-year-old daughter Blánaid chatted up German officials at embassy receptions and often gained useful nuggets of information to pass on to O'Flaherty.

O'Flaherty evades Gestapo

As the escape network developed, O’Flaherty’s activities came to the attention of the occupying German authorities. Herbert Kappler, head of the Gestapo in Rome, began specificallay to target the monsignor, who had some hair-raising escapes. One of the most dramatic of these occurred when he was visiting Prince Doria Pamphilj at his palace on Via del Corso. A resolute anti-Fascist, the prince, who was married to a Scot, was a supporter of O'Flaherty and helped to finance his activities. When the Germans discovered O'Flaherty's whereabouts they surrounded the palace.

The game was up, or so it seemed. O’Flaherty went down into the basement and as luck would have it, the winter’s supply of coal was being delivered through a chute into the basement. Taking off his clerical robes and covering himself in soot, O’Flaherty whispered to one of the coalmen explaining his predicament. Some minutes later he walked out past the SS troops, black as the ace of spades, the soldiers making way so as not to be contaminated by him. O’Flaherty made for the nearest church, washed, changed his clothes and returned to the Collegium Teutonicum.

Herbert Kappler

Kappler made at least three other unsuccessful attempts to capture O’Flaherty outside Vatican territory where his diplomatic immunity did not apply. One of these entailed hustling him across the white line separating Vatican territory from the Italian state, letting him go and having him shot when attempting to escape. Fortunately May was tipped off in advance.

While the two Gestapo agents pretended to be piously attending Mass in St Peter’s, May got four Swiss guards to remove them from the basilica. Instead of escorting them across the white line, however, the guards led them into a side street still in Vatican territory. Here they were left to the tender mercies of a group of tough Yugoslav partisans on May’s instructions. Given his lucky escapes, it is little wonder that Monsignor O’Flaherty was known as the Scarlet Pimpernel of the Vatican.

Jewish escapees

While meticulous records were kept of the POWs being helped through O’Flaherty’s escape line, details of names and payments being buried each night in tin boxes in the Vatican Gardens, no such records were kept of Jewish escapees. However anecdotes survive. In one poignant case a Jewish man had approached O’Flaherty with his young son saying that he and his wife cared nothing for themselves, but could he save the boy? He gave O’Flaherty his gold watch to pay for his support. O’Flaherty took the boy, but also arranged to get his parents to safety. After the war the boy was reunited with his family, carrying his father’s watch.

Kappler's imprisonment

A s soon as the war was over O'Flaherty turned his attention to helping Italian and German prisoners of war. When questioned as to why he was now helping the former enemy, his simple response was: “God has no country.” Kappler was sentenced to life imprisonment for war crimes, particularly for his leading role in Rome's Fosse Ardeatine massacre whose 335 victims included five of O’Flaherty’s helpers and one priest. Kappler’s only visitor for his first ten years in captivity, at the military prison in Gaeta south of Rome, was his former enemy number one, Hugh O’Flaherty, who eventually received him into the Catholic church and baptised him in 1959.

Rome's Oscar Schindler

The official records for the Rome Escape Organisation at the time of the liberation show that they were helping 3,925 escapees. We don’t know how many civilians and Jews should be added to that, possibly as many again. The plaque at the Collegium Teutonicum simply states that O'Flaherty saved over 6,000 people.

At the end of the film Schindler’s List, the Schindlerjuden gave Oskar Schindler a ring made of gold teeth fillings. It is inscribed with a quotation from the Talmud: “Whoever saves one life, saves the world entire.”

A fitting epitaph, too, for Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty.

Article by Fr Mícheál MacCraith