“I enjoy being 30, I drink my 30s like a liqueur, I don’t shrivel up in premature old age, cyclostyled on carbon paper. Listen, Cernam, White, Bean, Armstrong, Gordon, Chaffee: being 30 is great, and so is being 31, 32, 33, 34, 35! It’s a great age because it’s free, rebellious, illegal, because the stress of waiting for it is over, the melancholy of decline hasn’t started, because we’re finally lucid at 30!

If we’re devout, we’re staunchly devout. If we’re atheists, we’re staunchly atheist. If we’re dubious, we’re not ashamed of it. And we’re not afraid of pranks by the kids because we’re still kids, too, we’re not afraid of being scolded by the adults because we’re adults, too. We’re not afraid of sin because we’ve understood that sin is a point of view, we’re not afraid of disobedience because we’ve discovered that disobedience is noble. We’re not afraid of being punished because we’ve decided there’s nothing wrong in loving if we meet, of letting ourselves go if we get lost: we don’t have to reckon with the teacher any more and we don’t need to reckon with the priest and his holy oil. We reckon with ourselves, and that’s it, with our grown-up’s suffering.

We’re a field of ripe wheat at 30, no longer green and not yet dried up: the sap is coursing through us at the right pressure, full of life. Our every joy is alive, our every suffering is alive, we laugh and cry like we’ll never be able to again, we think and we understand like we’ll never be able to again. We’ve reached the peak of the mountain and everything is clear up there on the peak: the road we climbed and the one we’ll go down by. A little out of breath but still fresh, we won’t sit down half-way any more to look back and look forward and wonder about our future: so why isn’t it like that for you? Why do you seem like my fathers, crushed by fears, by boredom, by baldness? What have they done to you, what have you done to yourselves? What price did you have to pay for the moon? The moon is expensive, I know. It’s expensive for all of us, but no cost is worth that field of wheat, no price is worth that mountaintop. If it were, there’d be no point in going to the moon, we might as well stay here.

So wake up, quit being so rational, obedient, wrinkled! Quit losing your hair, quit feeling so down in your equality! Tear up the carbon paper. Laugh, cry, make mistakes. Hit out at the Bureaucrat watching his stop-watch. I say it in all humility, with love, because I respect you, because I see you as better than me and I wish you were much better than me. Much better, not just a little better. Or is it too late? Or has the System already crushed you, swallowed you up? Yes, that’s how it has to be.”

«Io mi diverto ad avere trent’anni, io me li bevo come un liquore i trent’anni: non li appassisco in una precoce vecchiaia ciclostilata su carta carbone. Ascoltami, Cernam, White, Bean, Armstrong, Gordon, Chaffee: sono stupendi i trent’anni, ed anche i trentuno, i trentadue, i trentatré, i trentaquattro, i trentacinque! Sono stupendi perché sono liberi, ribelli, fuorilegge, perchè è finita l’angoscia dell’attesa, non è incominciata la malinconia del declino, perché siamo lucidi, finalmente, a trent’anni!

Se siamo religiosi, siamo religiosi convinti. Se siamo atei, siamo atei convinti. Se siamo dubbiosi, siamo dubbiosi senza vergogna. E non temiamo le beffe dei ragazzi perché anche noi siamo giovani, non temiamo i rimproveri degli adulti perchè anche noi siamo adulti. Non temiamo il peccato perché abbiamo capito che il peccato è un punto di vista, non temiamo la disubbidienza perché abbiamo scoperto che la disubbidienza è nobile. Non temiamo la punizione perché abbiamo concluso che non c’è nulla di male ad amarci se ci incontriamo, ad abbandonarci se ci perdiamo: i conti non dobbiamo più farli con la maestra di scuola e non dobbiamo ancora farli col prete dell’olio santo. Li facciamo con noi stessi e basta, col nostro dolore da grandi.

Siamo un campo di grano maturo, a trent’anni, non più acerbi e non ancora secchi: la linfa scorre in noi con la pressione giusta, gonfia di vita. È viva ogni nostra gioia, è viva ogni nostra pena, si ride e si piange come non ci riuscirà mai più, si pensa e si capisce come non ci riuscirà mai più. Abbiamo raggiunto la cima della montagna e tutto è chiaro là in cima: la strada per cui siamo saliti, la strada per cui scenderemo. Un po’ ansimanti e tuttavia freschi, non succederà più di sederci nel mezzo a guardare indietro e in avanti, a meditare sulla nostra fortuna: e allora com’è che in voi non è così? Com’è che sembrate i miei padri schiacciati di paure, di tedio, di calvizie? Ma cosa v’hanno fatto, cosa vi siete fatti? A quale prezzo pagate la Luna? La Luna costa cara, lo so. Costa cara a ciascuno di noi: ma nessun prezzo vale quel campo di grano, nessun prezzo vale quella cima di monte. Se lo valesse, sarebbe inutile andar sulla Luna: tanto varrebbe restarcene qui.

Svegliatevi dunque, smettetela d’essere così razionali, ubbidienti, rugosi! Smettetela di perder capelli, di intristire nella vostra uguaglianza! Stracciatela la carta carbone. Ridete, piangete, sbagliate. Prendetelo a pugni quel Burocrate che guarda il cronometro. Ve lo dico con umilità, con affetto, perché vi stimo, perché vi vedo migliori di me e vorrei che foste molto migliori di me. Molto: non così poco. O è ormai troppo tardi? O il Sistema vi ha già piegato, inghiottito? Sì, dev’esser così.»

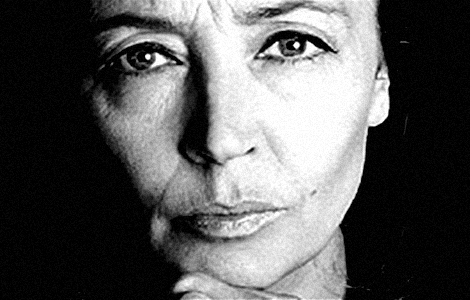

Oriana Fallaci

[Se il sole muore, 1965 Rizzoli]