Luca Signorelli's stunning fresco cycle adorns the S. Brizio chapel in Orvieto's cathedral.

By Martin Bennett

As a prelude to visiting the Sistine Chapel, one could take the train to Orvieto, an hour north of Rome, and view the frescoes which inspired Michelangelo’s Last Judgement.

On arrival at Orvieto station, the train prompts the reaction, ‘But where is it?’ Until a look upward reveals the town’s older part perched on a beetling crag. A small funicular railway transports you past vineyards famous for its classic Orvieto wine; "all Italy in a bottle" goes a phrase.

At the top of the funicular, take Via del Duomo to the cathedral which dominates the city's skyline. In the S. Brizio chapel to the right of the cathedral's main altar, there they are, body after perfect body, the hard-won art of anatomy standing on its own feet, or in take-off mode, or hurtling downward.

Whereas Michelangelo’s ignudi were the indirect result of strictly illegal nights spent studying corpses in Florence’s S. Spirito church morgue, Signorelli (1445-1523) who was 30 years senior to Michelangelo (1475-1564), is said to have stripped the body of his dead son (he had died of the plague) so that he could sketch it. Also instructive were the ancient statues resurfacing in Renaissance Rome and to which Signorelli as papal artist would have had privileged access.

In its four panels, painted between 1499 and 1504 the figures are not just muscular; many ripple with spectacular energy and movement. Vasari (1511-1574), who as a young boy may have met the artist, praises Signorelli’s “beautiful, bizarre and fanciful invention.” English essayist, Geoff Dyer, reflecting on his 1960s childhood, sees Signorelli’s blue-green-and-or-demonic-pink figures and their sometimes bat-winged aerobatics as a prototype for the comic strip.

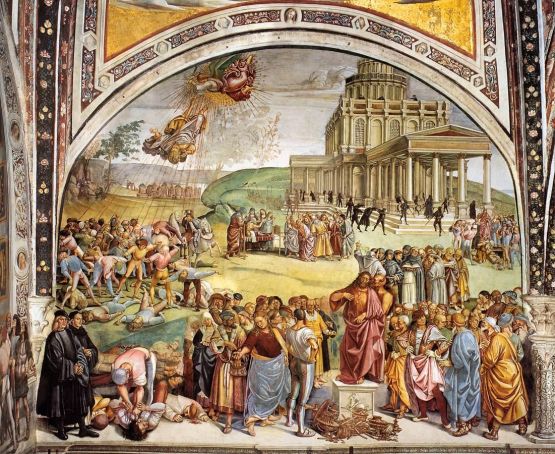

In the first fresco, Sermon of the Antichrist, the context is mostly biblical. The background temple might be in Jerusalem, yet the eerie spindly-limbed scarab-black soldiers infesting it are of Signorelli’s time, a reference maybe to the invading French armies of 1494 and 1499. In the foreground the Antichrist’s anything-but-benign features have been linked with firebrand preacher and subsequent heretic Savonarola, until his execution in 1498 the temporary nemesis of Signorelli’s Medici patrons. Biblical and Renaissance history intertwine. Note in the audience the curly-haired Cesare Borgia, Christopher Columbus and even Dante.

Hinting that the Antichrist's sermon is hardly orthodox, is a bearded figure settling with a prostitute and, worse, at Signorelli’s feet, an assassin finalising a series of murders. Off left, Signorelli portrays himself in black robes. Hands suitably crossed, he looks partly on at the scene, partly out at us, as if in warning, a trope later adopted by Michelangelo and by Caravaggio (1571-1610). Alongside, in monk’s habit stands Fra Angelico, the painter whom Signorelli replaced.

Into Antichrist’s ear a demon whispers to stir up maximum discord and mayhem. Accordingly in the fresco’s middle-ground the Antichrist, exploiting his disguise, replicates a false miracle to increase his support base as he raises a patient Lazarus-like from his sickbed. Elsewhere, below the temple steps, in a more obvious act of mischief, he orders the summary execution of two prophets, Enoch and Elias.

No wonder, a nearby cluster of Dominican and Franciscan monks consult the Bible to restore some theological order. Top right, flashing forward in time, Archangel Michael responds: the Antichrist’s eventual raid on heaven ends in a barrage of red rays zapping him down onto the heads of his stunned followers.

In the war between good and evil, more aerial combat decorates a chapel archway. Some victims try to block their ears, for this is a painting you can hear; doom foreshortened, others tumble toward the chapel floor, fancy Renaissance fashions powerless to protect them. The other side of the archway, sibyl and prophet gesture up to various portents familiar from Revelations: ships perch on mountain-peaks, a sickle moon turns to blood, and the sun goes black above earthquake-toppled monuments, further executions.

The panel depicting the Elect comes as a relief. The sky is not blue but fine-flecked gold, filled not so much with flights of angels as an orchestra. The foreground’s tautly-muscled figures stand looking blissfully upward. All the greater is the shock of the panel opposite, a hellish writhing free-for-all where green-buttocked and blue-faced devils twist, grab, whip, strangle and even bite into i Dannati.

Signorelli choreographs a nightmare of dislocation and contortions. More disturbingly still, he sets, himsef centre stage; this time his face and body have turned azure, a horn spiking his forehead as he abducts a young woman. The message, presumably, is that a potential for violence exists in each of us.

Echoing a thought from Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, art critic Simon Abrahams observes of the same panel: “Hell is not some biblical fantasy in faraway place, but in our heads.” True some of the figures reprise battle scenes decorating ancient sarcophagi, one pair (devil and lost soul) based on a satyr supporting a drunken Pan, and then displayed in Cardinal Rovere’s garden behind Rome’s SS. Apostoli church. To be imitated by Michelangelo and throughout the Baroque, the overall effect of muscular cruelty and outrage is Signorelli’s own. As Vasari says, "nothing had been seen like it."

Commentators have remarked that as Signorelli’s project progressed, his imagination waxed more and more fantastical. One goes as far as to attribute this to the free supply of Orvietan wine stipulated, along with house, grain and 575 ducats, in the 1499 contract.

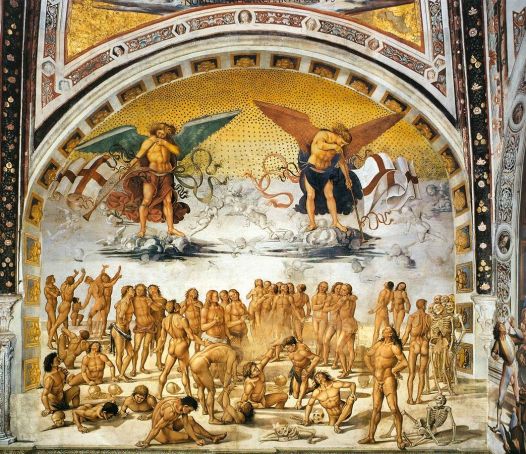

Finally, and most phantasmagorically, to The Resurrection of the Flesh. Vasari extols Signorelli’s “true method of making nudes and how, though only with craft and difficulty, they can be caused to be alive.” Beneath two archangels and various cherub-faced clouds, the first of the elect gather in harmonious groups, the three graces included, while other nudes clamber from cracks in the moonlike ground.

More remarkable still is the life conferred on some equally agile upwardly-mobile skeletons engaged in the same activity. Others laugh for joy as they line up for their own coat of skin and sinews. Critics note how the skeletons, compared to those in earlier Danses macabres, are both peculiarly expressive and unprecedentedly realistic. No bone is out of place. Art proves 40 years ahead of science, accurate medical prints of skeletons not appearing until Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica (1542).

The Book of Ezekiel asks: “Can these bones live?” Signorelli, however surprisingly, responds to the question with a dramatic meticulously-delineated “Yes.” It would be hard to find a fresco cycle with a longer reach. As befits the subject matter, between one action-packed panel and the next, epochs merge with a sweep of the gaze; time, or the end of of it, takes on a new dimension.

Tickets for the Duomo and Chapel of S. Brizio cost €5. Opening times vary throughout the year. For visiting details see www.orvietoviva.com.

This article was published in the March 2020 edition of Wanted in Rome magazine.

General Info

View on Map

Signorelli's beautiful, terrifying frescoes in Orvieto

Piazza del Duomo, 26, 05018 Orvieto TR, Italy