Rome’s social housing was built for the poor but is ending up in the pockets of the rich.

Mike Dilien

“FOR RENT: Largo C. Ricci, near Colosseum. Four 60-sqm apts. Splendid view of Roman Forum. €41 /month.”

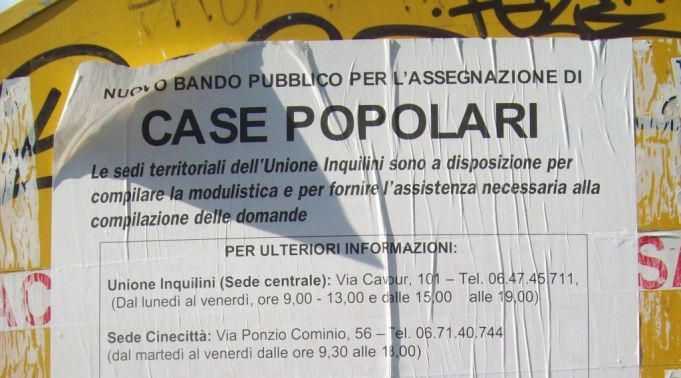

Rome’s public housing entity, Azienda Territoriale per Edilizia Residenzale (ATER), offers a wide range of accommodation, from flats on the outskirts of Rome and houses in typical rioni to housing of all sizes from the outskirts to the historic centre. Every Rome resident, whether Italian or foreign, can apply for a council house. To be considered, a candidate's family must earn a total annual income of no more than €20,345 and not own, or be a beneficiary of, any other property.

In a city whose yearly 13 million visitors make 29.5 million overnight stays, at least 100,000 people in Rome have difficulty in finding a place to live, according to Italian business newspaper Il Sole 24 ore. While desperate citizens are squatting in at least 110 buildings, associations advocate affordable housing. ATER's council housing is highly affordable since tenants pay rent based on their income. Even for a spacious apartment in a top-notch location rent is between €7.75 and €500 a month. ATER’s waiting list, however, is long. Too long because many people are renting a council house illegally.

Abuse of system

In 2012, ATER and the Guardia di Finanza (GdF) discovered that 12,500 ATER tenants had declared an amount less than their actual income. People who earned €80,000 per year were living in Rome’s historic centre for €80 a month. Even well-to-do Romans, people who own property and yachts, who have businesses and invest on the stock exchange, were benefiting from council housing. On the Aventine hill for example, some tenants were discovered paying no more than €500 a month for a charming villa with garden. Luxury cars stand parked in front of these villas that are monitored by security cameras. For 15 years Lazio’s former governor, Renata Polverini, and her entrepreneur husband, enjoyed a council flat in S. Saba, a stone’s throw from the Baths of Caracalla.

ATER, which dates from 1903 and combines several former public housing entities, manages 53,000 dwellings and 150,000 tenants. The entity, however, is facing a parallel renting market. Absentee ATER tenants, living in Rome or elsewhere, sublet their council home on a black market. Other people, often with the help of lawyers, rent out council homes that stand empty, forging papers, changing locks and letterboxes.

After ATER and the GdF published their findings, the Arena television programme on the state RAI network hosted a debate between ATER’s then managing director Bruno Prestagiovanni and Anna Maria Addante, president of the association of ATER tenants. Ignazio Marino, Rome’s then mayor, also participated in the discussion.

Illegal subletting of council houses

Addante denounced the widespread practice whereby absentee tenants sublet their council house. They charge a rent that is substantially higher than the amount they pay ATER. They also ask their tenants entry fees between €20,000 and €50,000.

In Rome, affordable housing is so scarce that people have been known to move into a council house as soon its occupants are away for a while. Some tenants have returned home after a stay in hospital to discover the lock has been changed and someone else is living in there.

During the heated television debate, ATER’s managing director defended himself pointing out that whereas ATER, which owns and maintains the property portfolio, depends on the Lazio region, the office that assigns the dwellings depends on the city.

Addante said that she reports illegal tenants – some even repeatedly – but neither ATER nor the city office ever acts.

That night, Addante’s car was set alight.

This year, exactly 20 years after a media scandal revealed that politicians, entrepreneurs and VIPs in Rome were renting premium council property at bargain prices, and three years after the joint investigation of ATER and the GdF, the daily newspaper La Repubblica reported that a new task force has established that two thirds of ATER tenants are illegal.

Criminals infiltrate social housing

For example, recently it became public that members of the Casamonica criminal clan are living in council houses from Prati to Pigneto. The family is active in construction and restaurant businesses, but also in usury and drug trafficking. Italy’s anti-mafia commission has estimated that the clan’s real estate is worth €90 million. Each time the police arrests one of the clan members, it confiscates villas, land, jewellery and the obligatory garage stacked with Ferraris. The parents of the head of the clan are living in a council house for which they pay €7.75 a month.

Because many ATER tenants did not pay their rent regularly, or at all, and maintenance costs of the buildings were soaring, ATER began divesting one-third of its housing stock in 2007. Tenants were given priority to buy the council home they were renting. In areas like Flaminio, large apartments went for prices that would not have bought even a garage. For example, in Piazza Giuseppe Mazzini, a local politician bought an apartment for €250,000 just a couple of hours after the tenants had bought it from ATER for €206,000. The apartment’s market value was €880,000. After 775 council houses and apartments had been dumped at bargain prices, the city halted the divestment programme.

Yet, by the end of last year, delayed and unpaid rent had soared up to €2.8 million. ATER resumed its divestment programme and sold 382 dwellings. Towards the end of this year, it will sell another 700. Again, current tenants have priority and benefit from a 30 per cent discount on the market price.

Irregularities in the management of council housing is not exclusive to Rome, but chancing upon a place in one of the world’s most beautiful cities, with a view of some of the world's most spectacular monuments, is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Many council estates are in uptown areas like Parioli and Prati, trendy places like Testaccio and Trastevere, or the latest place to be, Garbatella. In addition, the architecture of several of the estates is of a remarkably high standard.

Profiting from resale of cheap council apartments

Some owners who snatched up public property cheaply, sold it at top market prices sometimes overnight. Other owners bought entire blocks. In the Trieste neighbourhood, a member of parliament bought a whole block of council apartments and turned them into luxurious flats. The new, market-rate rent pushed out all original ATER tenants, according to a report in Italian newspaper Il Fatto Quotidiano.

Renato Rizzo, president of the capital’s union of tenants, the Unione Inquilini Roma, claims that: “The city divests its public housing assets, allowing for speculation – both small and large-scale.” The union is shielding two council houses, one in Trastevere and one in Lungotevere, from property speculation.

Even in today's downward property market, real estate prices in the centre of Rome keep rising. According to the real estate franchise Tecnocasa, property investors in Rome are hunting for apartments in order to convert them into B&Bs.

Apparently, council homes, especially those located in former working-class neighbourhoods, make excellent short-term lettings. Online adverts that list lodgings in Garbatella, Monti, Trastevere and Testaccio herald their surroundings’ “laid-back and bohemian flair.”

Shortage of social housing

Ironically Rome’s housing shortage does not stem from a shortage in houses. In 2009, more than 245,000 apartments stood empty. At Rome’s average of 2.3 inhabitants per home, these empty apartments could accommodate half a million people: enough to shelter all the residents of Appio-Tuscolana, Rome’s most populous quarter, according to Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera.

Every day, banks foreclose on 22 Roman homes. Until ATER assigns them a council house, people who defaulted on their mortgage payments are lodged in dormitories by the city – families with three children are living in 45 sqm. ATER's waiting list counts 30,000 applicants. On average, there is one dwelling for every 100 applicants. Last year ATER assigned 350 applicants a council house.

Currently, four council apartments of 60 sqm in Largo Corrado Ricci, near the Colosseum and with a view on the Roman Forum, risk either being transformed into a hotel or annexed to one of both adjacent hotels. “From council houses to hostels,” comments the head of Rome tenants' union.

While council housing is being turned into accommodation for tourists, families with young children wait years for a council house, living in dormitories and campers.