St Isidore's marks 400 years in Rome

Irish Franciscans celebrate four centuries of St Isidore's with a major conference in Rome.

This year marks the 400th anniversary of St Isidore's College, an Irish Franciscan landmark and Ireland's national church in Rome.

The college was founded at a time when Catholics faced religious persecution in Ireland, during the reigns of Queen Elizabeth I and James I in the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

This turmoil led to a multitude of Irish colleges emerging on the continent, including St Isidore’s, to provide a haven for exiled Irish clergy and those seeking religious formation.

The college’s origins are shared by Ireland and Spain, a fact reflected in the sculptures of two saints on the building's Rococo façade: St Isidore of Madrid and St Patrick of Ireland.

The story starts in 1622 when a group of Spanish discalced Franciscans founded the building as a convent dedicated to the newly canonised Isidoro, a farmer and holy man from the 11th century.

However after running into financial debt, they were forced to abandon their incomplete home, near Piazza Barberini, where it still stands today.

The college is located in a district known as “Capo le Case” (meaning head of the houses) in an area of Rome where the city once met the countryside.

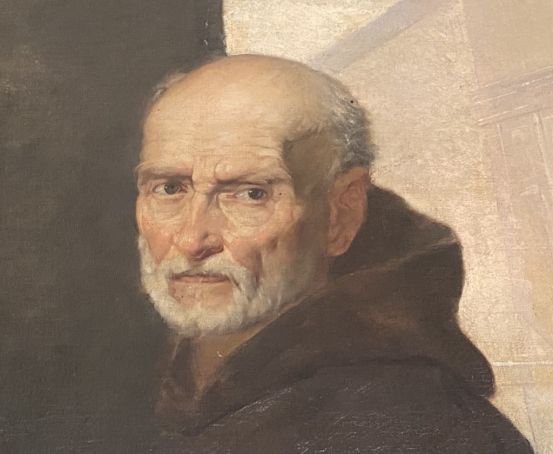

Luke Wadding

Fr Luke Wadding, an Irish Franciscan scholar living in Rome at the time, offered to complete the debt-ridden building project and take over St Isidore's.

He had one condition: that he could turn the convent into a seminary to train young Irish Franciscans for priestly service on the home mission in Ireland.

In addition to completing the church, Wadding enlarged the building – originally designed to host 12 people – to accommodate 60 friars.

The new community took up residence in 1625 and within five years Wadding had paid off the debts accumulated by the previous occupants, thanks to donations from benefactors including Pope Urban VIII.

Although it retained the patronal name of the Spanish saint from Madrid, Wadding was keen to underline the Irishness of the new college.

This is evidenced by the frescoes of Ireland’s patron saints – Patrick and Bridget – on either side of the entrance to the church, beneath old Gaelic script from an eighth-century text.

Irish identity

The current Guardian of St Isidore’s, Fr Mícheál Mac Craith, says this was Wadding’s way of emphasising Ireland’s national identity.

“With its verses in Old Irish, St Isidore’s is the only church in Rome that uses its vernacular language in its portico” – Mac Craith said – “It would seem that when Wadding came here, he wanted to make a very strong statement: this is an Irish establishment.”

Mac Craith – a distinguished scholar and professor emeritus of Modern Irish at the University of Galway – believes that the prominent depictions of Patrick and Bridget also served to make the point that: “Ireland is a separate kingdom, it has its own saints and its own language: the Irish have come to town."

Restorers from the Italian Ministry of Culture discovered recently that Patrick was initially portrayed beardless, in keeping with the earliest iconography of the saint.

“But Wadding was trying to present him to the Vatican as the Irish Moses, a patriarchal figure”, Mac Craith said, “so the beard added that necessary gravitas”.

The five-month restoration of the frescoes was completed just in time for St Patrick’s Day, on 17 March, when the city’s Irish community thronged the exquisite, art-filled church.

St Patrick’s Day

In his introduction at the Mass that morning, Mac Craith paid tribute to Wadding for founding St Isidore’s as well as for his key role in establishing Ireland’s national day in 1631.

“Wadding was actively involved in the reform of the Roman Breviary and in the compilation of a new universal calendar of the church” – Mac Craith said – “Up to then St Patrick was just a local Irish saint, but Wadding insisted and prevailed on the Vatican to mandate that the feast of St Patrick be celebrated all over the world and not just at home: from Derry to Dubrovnik, from Limerick to Lesotho, from Roscommon to Rwanda.”

As part of a long-standing tradition, the St Patrick’s Day Mass in Rome is presided over each year by the rector of Rome’s Pontifical Irish College which Wadding founded in 1628 for the training of diocesan priests.

In Rome today a #StPatricksDay Mass at St Isidore’s College, which celebrates its 400th anniversary this year, ended with a nostalgic rendition of Hail Glorious St Patrick. pic.twitter.com/0ETylBlQ4u— Wanted in Rome (@wantedinrome) March 17, 2025

Wadding accomplished all of this within a decade of arriving in Rome in 1618, at the age of 30, following his studies in Lisbon.

Immaculate Conception

His arrival in the Eternal City came about after King Philip III of Spain chose him as theological adviser to a delegation sent to petition Pope Paul V to define the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception.

The mission failed and the royal delegation returned to Spain, however Wadding stayed in Rome where he would spend the rest of his life.

He also never lost sight of the reason for his original mission. As a writer he is best known for his publication of the complete works of Duns Scotus, the mediaeval Franciscan who first developed the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, which asserts that the Virgin Mary was free of original sin.

Wadding was a leading light in investigating this doctrine and his findings proved fundamental to its eventual definition as a dogma, in 1854.

Mac Craith notes that St Isidore’s is “not just an important place for Irish people, it’s very important for the history of the order and the history of the Church.”

Artistic treasures

Wadding can take credit for the fact that the college’s church is a treasure trove of 17th-century Italian art, achieved by hiring the best Roman artists of the time with the financial assistance of his Spanish patrons.

In a happy coincidence, the great art theorist Giovanni Pietro Bellori managed St Isidore’s finances from 1653 to 1684 and – encouraged by Wadding – embraced the chance to showcase his aesthetic ideas.

Bellori introduced Wadding to Carlo Maratti whose Flight into Egypt in the church’s Chapel of St Joseph sealed the young artist’s fame.

The painting depicts Joseph and Mary hand in hand, which Mac Craith describes as “a degree of intimacy you don’t often find in 17th-century painting.”

The church’s high altar is decorated with a painting of St Isidore by Andrea Sacchi, Maratti’s master, who depicted the saint contemplating the Virgin Mary and Child Jesus while angels carry out his work in the fields.

Mac Craith describes the church as “gently Baroque,” suggesting that Bellori “kept a lid on” the ornate exuberance associated with the movement.

However the de Sylva Chapel, a jewel to the right of the main altar, is unashamedly Baroque in its magnificence. The chapel was designed for Portuguese nobleman Rodrigo Lopez de Sylva, as a funerary space for his family, by none other than Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

The chapel is adorned with a painting by Maratti of the Immaculate Conception, complete with an angelic orchestra, and sculptures of the four virtues: Justice, Peace, Prudence and Charity. The latter’s exposed breasts caused an outcry in the Vatican at the end of the 19th century, leading to the “monumento scandaloso” being concealed with a bronze garment that was not removed until the 1980s.

Other treasures in the church include the Barberini chapel, featuring the family’s bee motif, and a monument to the 19th-century Irish artist Amelia Curran, famous for painting a portrait of the English Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, her neighbour on nearby Via Sistina. Curran was friendly with the poet’s wife, Frankenstein author Mary Shelley, and painted a portrait of the couple’s child Wilmouse before he died in Rome aged three.

The church is home to a poignant funerary monument dedicated to Octavia Catherine Mary Byran, a young Irish woman who died of a fever in 1846, the night before she was due to marry Prince Scipio Borghese, a scion of one of Rome’s noblest families.

Her funeral in St Isidore's provided the sad occasion for John Henry Newman, who became a saint in 2019, to preach his first sermon as a Roman Catholic. He was heavily pressurised into it by the head of the Borghese family who obtained the necessary permission for him from the Vatican, even though he had only started to study for the priesthood.

"By all accounts the sermon was an unmitigated disaster", Mac Craith said, noting that the tragic Catherine was buried in her wedding dress and that her effigy resembles Ophelia.

Napoleon and Nazarenes

Around the turn of the 19th century St Isidore’s was occupied by Napoleonic troops who stole two paintings by Maratti from the Chapel of the Crucifixion.

Visitors may notice blank spaces in the side chapel, to the left of the entrance to the church, where the paintings once hung. “Leaving the spaces blank instead of getting replicas tells you more about the sordid realities of history”, Mac Craith mused.

The Nazarene painters, a movement of German artists led by Johann Friedrich Overbeck, rented rooms at the college from 1810 to 1814. Inspired by painters of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, the group worked and lived together in a monastic-style existence, believing that all art should serve a moral or religious purpose.

Some say the artists lent their name to the street where St Isidore’s stands – Via degli Artisti – however Mac Craith said there is good reason to believe that this evocative appellation dates much earlier.

Franciscan scholarship and learning

Wadding established a precious library at St Isidore’s, amassing 5,000 volumes. It was regularly mentioned in guidebooks to Rome in both the 17th- and 18th centuries as a notable library. Today it contains more than 24,000 volumes and its archive of early Franciscan history is “one of the richest in the world", Mac Craith said.

Wadding collected these manuscripts when he was writing the Annals of the Franciscan Order from the beginning up to the Reformation. They were published in eight very large volumes between 1625 and 1634, in what is considered his most significant work.

A splendid cloister filled with orange trees and surrounded by early 18th-century frescoes of Franciscan life is hidden away in the heart of St Isidore’s. To one side of the cloister is the Aula Magna, an important room where students defended their theses down through the centuries.

The grand hall is decorated with frescoes of renowned Irish Franciscan scholars and bishops alongside the saints Francis, Bonaventure and Anthony.

These frescoes, executed by Fra Emanuele da Como in 1679-71, depict Irish Franciscans who contributed to developing the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception.

A speech bubble emanating from the mouth of each says something praiseworthy about Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, directing the eyes of the spectator to the image of Our Lady of Immaculate Conception in the centre of the far wall.

The large fresco to your right as you enter the Aula shows the scholars of St Isidore's studying in the library. It has a long inscription in Latin underneath asserting that the Irish nation, destroyed at home by Cromwell, is being recreated in Rome through the scholarship of Irish Franciscan exiles.

Mac Craith recalls how Dublin politician Gary Gannon, during a recent visit to St Isidore’s, was amazed to discover a location “so defiantly Irish” in the middle of Rome.

The scholars depicted in the Aula are linked to both St Isidore’s and the Irish Franciscan college in Louvain, founded in the Belgian city in 1607. The frescoes serve as a reminder that Irish Franciscan centres of scholarship and spirituality have flourished on the European continent since the early 17th century.

This rich tradition of learning continues today with the ongoing formation of Franciscan friars at St Isidore’s, a venerable Irish institution whose Hibernian roots are deeply intertwined with those of Spain, Rome, Louvain and Europe itself.

Wadding, who served as rector of St Isidore’s for 30 years, was also Ireland's first ever accredited Irish ambassador. The Confederation of Kilkenny in 1642 appointed him with letters patent as their representative in Rome.

He died on 18 November 1657, at the age of 69, and is buried in the crypt of St Isidore's.

The Irish in Rome conference

Leading academics will gather in Rome from 28-30 May for a three-day symposium to commemorate 400 years of an official Irish presence in Rome, beginning in 1625 with the establishment of St Isidore's.

Titled ‘The Irish in Rome,’ the conference will be co-hosted by the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies at the University of Notre Dame and St Isidore’s College.

The conference will feature three plenary sessions, two featured author readings, and a series of panels that engage with the cultural exchanges and historical impacts arising from four centuries of Irish clerical, scholarly and artistic presence in Rome.

Events will take place at St Isidore’s and Notre Dame’s Rome Centre. Plenary sessions and panels are free and open to the public to register for online or in-person attendance, with a registration deadline of 30 April.

The full programme and registration forms can be found on the conference webpage.

Article by Andy Devane

Cover image: Fresco of St Patrick in the portico of the Church of St Isidore's. Photos by Wanted in Rome.