The kidnapping and assassination of Aldo Moro

The kidnapping and murder of Italy's former prime minister Aldo Moro by the terrorist group Brigate Rosse.

On 16 March 1978, Aldo Moro, former Italian prime minister and president of the Christian Democracy, was kidnapped. The kidnapping occurred in Via Mario Fani in Rome, by far-left terrorist organisation the Red Brigades.

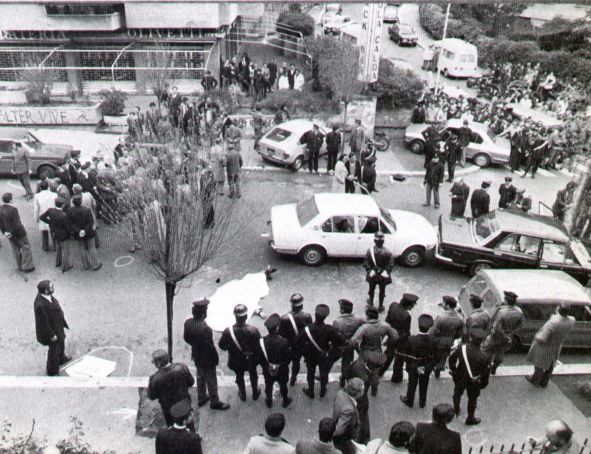

The attackers gunned down Moro's five personal bodyguards before taking him hostage. Then, on 9 May 1978, after 55 days of disputes, extensive searches, and proposed compromises, Moro was killed. His body was found in the back of a red Renault 4 on Via Michelangelo Caetani in the historic centre of Rome, very close to both the Christian Democrat and Italian Communist Party headquarters.

More than 40 years later, many of the details of Moro's kidnapping are still heavily disputed and there is much that remains unknown. The event remains one of the seminal moments in the history of Italian politics and the infamous Anni di piombo (years of lead).

To fully grasp the significance of this event it is important to understand who Aldo Moro was and why a far-left terrorist organisation such as the Red Brigade would target him in particular. It is also necessary to dive into the still hazy details to gain an understanding as to how the kidnappers managed to elude some of the world's top intelligence agencies for 55 days, and so well, that many of the details remain unknown even today.

Moro, the Historic Compromise, and the situation in Italy

Aldo Moro was Italy's 38th Prime Minister, holding office from December 1963 to June 1968 and again from November 1974 to July 1976. He was one of Italy's longest-serving post-war prime ministers and is widely considered to be one of the greatest and most popular leaders in the history of the Italian Republic.

In addition, Moro also served as Minister of Justice and Public Education during the 1950s as well as Minister of Foreign Affairs. He is considered one of the fathers of Italy's centre-left political movement. Known as an intellectual and patient mediator, Moro implemented several social and economic reforms that helped modernize the country.

In March 1959, he became secretary of the Christian Democracy (DC), a position he would hold until 1964. Founded in 1943 in Nazi-occupied Italy, the DC was the successor of the Italian People's Party. The centrist, catch-all, Catholic-inspired party featured both left and right-leaning political groups and would remain one of Italy's dominant political parties until its demise in 1994. The Italian Communist Party (PCI) was one of the largest opposition parties to the DC.

In the 1970s, after watching the Marxist Allende Government get overthrown in Chile, PCI General Secretary Enrico Berlinguer was convinced that far-left governments could only survive in democratic countries if they made alliances with more moderate parties. This lead to Berlinguer proposing a political alliance between the DC and PCI in 1973. The proposal was launched in communist magazine Rinascita and was embraced by Moro. Berlinguer wanted to distance the PCI from the USSR and create “Eurocommunism.”

Although the proposal was embraced by Moro, other center-left groups like the Italian Republican Party (PRI) and the Italian Socialist Party (PSI), strongly opposed the alliance. Some saw the "Historic Compromise" as nothing more than a way for two of the most widely supported parties to maintain a firm grip on power in the country.

Several members of the DC left the party as a result of the compromise. The PCI also saw several radical communists boycott the government in protest. Following the compromise, there was an increase in far-left terrorism, mostly by the Red Brigades (BR).

It is also important to remember that this was at the height of the Cold War. While most other Western Democratic countries had landed on the capitalist side of the divide, Italy remained on the fringe. The widespread support for the PCI worried many western countries and the fact that they would now hold a legitimate government seat in one of Europe's most powerful countries only intensified the situation.

The Italian government's lack of acknowledgment of the threat of far-left terrorist organizations was another worrying prospect. In the decade leading up to the Moro case, Italy had seen a drastic rise in domestic terrorism, but the government and country as a whole had adopted a feeling of resignation towards it. Some far-left terrorist organizations were not even regarded as such.

Terrorist group Prima Linea, for example, was not considered an armed gang, but simply a subversive association. The BR was also not considered a threat in the country, many even believed that the group had more or less ceased to exist in 1976 as a result of police intervention and counter-terrorist measures. However, this was a drastic undersight to the true threat the country faced. This was made clear on 16 March 1978, when the BR kidnapped Aldo Moro.

The Assault

When Moro's convoy entered Via Fani, Rita Algranati alerted the terrorists by waving a bunch of flowers and then rode away on a moped. With the signal that their target had arrived, the Red Brigade members sprung into action. Moretti cut off the road in front with his car, then Ricci's attempt at an escape maneuver was thwarted by a Mini Minor parked in the way. At this point, four gunmen identified as Valerio Morucci, Raffaele Fiore, Prospero Gallinari, and Franco Bonisoli jumped out of the bushes armed with machine pistols.

All four of the gunmen were wearing Alitalia airline crew uniforms to avoid friendly fire since not all of them had worked together before. Within minutes, all five bodyguards were killed with only Iozzino being able to react by firing two shots before he was killed. Almost as soon as the assault started, Moro was forced into a Fiat 132 next to his car before being taken away.

The Days of Imprisonment

Shortly after the assault, the BR claimed responsibility for the kidnapping in a phone call to the Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata (ANSA). The significance of the timing and date chosen by the BR to carry out the kidnapping should not be ignored. At 10.00 that same day, Moro was scheduled to go to the Chamber of Deputies where a new government, led by Giulio Andreotti, was to announce its policies.

The Fourth Andreotti cabinet was the first Christian Democratic Government to have the support of the Italian Communist Party, thanks to Moro’s Historic Compromise. It would be the first time that the Communist Party had a position in government since 1947.

At 10.00, the president of the Italian Chamber of Deputies, Pietro Ingrao, stopped the session to announce the kidnapping. The emergency created by the situation meant that the PCI would no longer hold a position in government. Instead, another right-center cabinet under the firm control of the DC would be installed. Later that day, one of the cars used by the terrorists was found in via Lucinio Calvo, about a hundred meters from Via Fani.The next day, the police arrested a young clerk who they suspected was involved in the kidnapping, only to release him two days later. It is worth noting that this was a blunder made by the police for not thoroughly investigating and shadowing the suspect in question before arresting him. It was not the last mistake made by the police during the hunt for Moro.

That same day, another car used by the terrorists in the assault was found in via Lucinio Calvo. This raised questions about whether the car was there before, or if the BR planted it there. At this point, the area around where the assault took place was highly guarded and was under 24-hour police surveillance, making it hard to imagine the car could have been planted there. However, it is also equally hard to imagine that the car could have evaded police detection for this long.

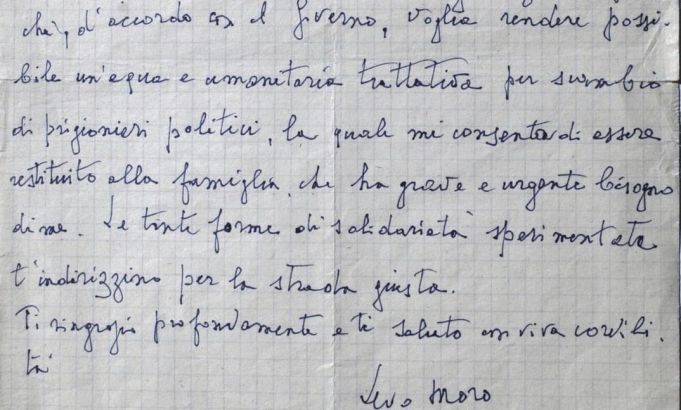

Throughout Moro's imprisonment, he would write 86 letters, of which between 50 to 60 were delivered to their intended destination. The letters were addressed to the main members of the Christian Democracy, his family, and Pope Paul VI. The BR would also put out nine "communications" in which they revealed their motivation for kidnapping Moro, as well as inform the public of how Moro's trial in the "People’s Court of Justice" was transpiring.

Moro's plea

While he does not state it directly in the letter, it is unmistakable that Moro is pleading with Italian authorities to bargain with the BR for his release. In the letter, Moro argued, "the doctrine according to which advantage must not accrue to kidnapping does not apply to political circumstances where a sure and incalculable damage is done not only to the person but to the state itself.”

It is worth noting that at this point the BR had not given any detail or presented any terms for Moro's release. It should also be assumed that while the letter bore his signature and his style of writing was recognizable, he did not enjoy full freedom to write. Whether or not his captors instructed him to suggest negotiating for his release at this point is anyone's best guess. At the time, however, 15 members of the BR were on trial in Turin. Though the trial had been halted due to the initial shock of the kidnapping, by now it had resumed and was proceeding as scheduled.

Moro also implicitly stated that the Church could be used as an intermediary in any potential negotiations, as they had done in other terrorist cases in the past. The Holy See would, on several occasions, send pleads to the BR to release Moro. In addition to his plea for authorities to bargain for his life, Moro also warned of the damage that could come to the state should he be forced to disclose secrets. "There is the risk that I will be induced to talk in a manner that could be dangerous…" However, despite Moro's and the terrorists' best efforts to negotiate for his freedom, Italian authorities, after much deliberation, decided that they would not meet the terrorist demands.

The Red Brigades' fourth communication was received on the 4th of April along with a letter from Moro to Zaccagnini. In the communication, the BR states that the idea that Moro's previous letter to Cossiga was written under their dictation "are as treacherous as they are stupid" as it included a belief that the BR does not hold.

In the letter, Moro once again pleaded with Italian authorities to seek a compromise and negotiate for his freedom. At the time when it was written, Moro had been imprisoned for fifteen days and was beginning to become anxious by the inaction of those in a position to negotiate. This was made clear when he states "Time runs fast and unfortunately there is not enough. Any moment may be too late."

He is also aware of the consequences that not only he, but the DC and state as a whole will face should they fail to come to a peaceful resolution stating "another more terrible and equally dead-end cycle will begin." Towards the end of the letter, Moro writes "in truth, I also feel a little abandoned by you." However, while in this letter Moro clearly states his desire to negotiate for his freedom, the state continued to stand against coming to any kind of compromise. If it is to be assumed that this letter was written under the dictation of the BR, we now have reason to believe they were willing to negotiate.

On the 6 April, the BR's fifth communication was received along with an autographed attack by Moro on Taviani, Cossiga, Zaccagnini, as well as the whole of his party. In the letter, Moro writes "Of course, I cannot prevent myself from underlining the wickedness of all the Christian Democrats who did not agree with my position… And Zaccagnini? How can he stay tranquil in his position? And Cossiga could not devise any possible defense? My blood will fall over them." Moro had at this point run out of patience, and his and the BR's attempts to coax the state into negotiations had failed. Thus, they decided to try a different tactic.

On the 15 April, the BR released their sixth communication in which they stated “Aldo Moro has been found guilty and has been condemned to death.” Despite this frightening revelation from the BR, Italian authorities refused to budge, believing it to be just another ploy by the terrorists to coax them into action.

The Brigate Rosse's apartment

The 18th of April was perhaps the most important day during this saga since Moro was kidnapped just over a month prior. Two key events would come to define this day. The first was the release of what was supposedly the BR's seventh communication. It announced they had gone ahead with Moro's execution and that his body had been thrown into the Lago Duchessa, a small mountain lake to the northeast of Rome. Authorities searched the icy waters, but no sign of Moro’s body was found. It turned out that this message had been forged.

The second pivotal event was the discovery of a BR base in an apartment in via Gradoli in Rome. It was the private residence of BR national leader Mario Moretti and was discovered after firemen responded to a water leak by the tenant below the apartment. The cause of the water leak was mysterious and authorities found around one-thousand pieces of incriminating evidence inside the apartment. (More on both of these events later…)

Moro is still alive

After five days of uncertainty as to Moro's condition, an ultimatum was presented on the 20th of April when the BR released its seventh communication. In it, they declare that Moro is alive and they are prepared to release him in exchange for "Communist prisoners." They set the deadline for the 22nd at 3 p.m. and delivered a photograph of Moro holding the previous days' La Republica to the above paper. This is the first time that the BR openly states that they are willing to negotiate for Moro’s freedom and offer their terms.

The Italian authorities, once again, did not respond to the demands of the BR. Then on the 24th of April, the BR released their eighth communication in which they name all thirteen Communist prisoners that they want to be released in exchange for Moro. All thirteen prisoners were currently on trial in Turin. The BR and other far-left terrorist groups had been carrying out numerous terrorist attacks in Turin as well as other cities in the north such as Genoa and Milan since the start of the trial and the Moro saga. The attacks which were targeted at politicians, prison wardens, and police officers were intended to coax authorities into negotiating.

Andreotti's message

Andreotti, one of Italy's former prime ministers, delivered a message on television on 28 April. "How would the Carabinieri, the police, and the prison guards respond to the Government's negotiating - behind their backs and in violation of the law - with those who have made havoc of that law? And what would the wives, orphans, and mothers of those who have fallen while accomplishing their duty have to say?" This sent a clear message that Andreotti and the Italian government had no intention of negotiating with the BR for Moro. He would later confirm the government's refusal to negotiate on the 3rd of May.

The Red Brigades would send their ninth and final communication on 5 May. The cryptic message from them read “We conclude the battle started on 16 March with the executing of the sentence to which Moro was condemned.” Interpretations of this message were mixed.

Aldo Moro's dead body

Subsequent hypotheses, aftermath, trials, theories, and further findings and information.

In the aftermath of the event, the country yearned for answers. Though Moro’s fate was now sealed, there was no feeling of closure as so much remained unknown. Italian authorities would name ten members of the BR who they sought to capture and put on trial for the abduction and murder. Of the ten, only two managed to evade capture, Alvaro Lojacono who fled to Switzerland, and Alessio Casimirri who fled to Nicaragua.

The others, Corrado Alunni and Marina Zoni were arrested in 1978, Valerio Morucci, Adriana Faranda, and Prospero Gallinari in 1979, Mario Moretti in 1981, and Barbara Balzerani in 1985. Rita Algranati was the last to be arrested when she was captured in Cairo in 2004. Algranati remains the only one still living who is behind bars. The others were all subsequently released on parole, or due to disassociation and collaboration. Even Mario Moretti, former national leader of the BR who later admitted to killing Moro was semi-freed in 1997 and is still alive today.

The trials that followed provided some answers to the Moro case, however, we are still left with more questions than answers. One important piece of information that has never been revealed is the location of Moro's prison. Another commonly held assumption is that the BR didn't act alone in kidnapping Moro. While they certainly could have had help from other domestic far-left terrorist organisations, there is reason to suspect that much larger and more powerful forces and organizations had a hand in it. Although there are no conclusive answers to either of these questions, there has been no shortage of theories.

Crisis Committees

On the same day Moro was kidnapped, Francesco Cossiga formed two “Crisis Committees.” The first, chaired by Cossiga himself, was a technical-operational-political committee. It included members of Italy’s military and intelligence services (SISMI and SISDE) as well as secret information agency CESIS, UCIGOS, the police prefect of Rome, and top commanders from the Italian Police Forces, Carabinieri, and Guardia di Finanza. The second group was an information committee, which included members from CESIS, SISDE, SISMI, and SIOS.

These new committees, while good in principle, were ineffective in fighting Italy’s modern terrorist threat. Even with the alarming growth of terrorism in the country over the last decade, the committees were operating according to old standards dating back to the 1950s. This was largely due to the country’s resignation towards left-wing terrorism, with many groups not even being labeled accordingly.

Theories of the Assault

The assault itself has been the subject of much speculation and debate. Official reconstructions of the trials indicate that eleven people took part in the assault, however, this number, as well as the identities of those involved, are widely disputed. The coordination and precision with which the assault was carried out have cast further doubt on the accounts given by the terrorists during their subsequent trials.

The knowledge of where and when Moro would be that morning is another messy detail. Moretti claimed that he had been studying Moro's daily moves since 1976. However, Moro's escort changed the route daily. Whether or not they followed a pattern for changing their route is unknown. The terrorists involved in the assault also took several precautions beforehand, such as slashing the tires of a florist to remove a key witness. This does however show that they did know the exact route Moro would take, how they managed to acquire that knowledge has raised many questions.

The identities and number of terrorists involved as well as the precision with which the assault was conducted raise even more suspicions. Investigators recovered 93 bullets at the scene of the assault, 49 of which had hit their targets. The bullets recovered indicated that the gunmen were armed with two different submachine guns, an FNAB-43, and a Beretta M12. However, one question that remains is how Moro was almost completely unharmed, only suffering a small wound in his thigh. This is what many holds as clear evidence of the presence of a marksman at the assault. Further evidence that strengthens this theory comes when several members of the BR, including Valerio Morucci, claimed that they had practiced only rough shooting training before the attack.

Several sources identify Giustino De Vuono, an Italian intelligence member and former marksman for the French Foreign Legion, as being present during the assault. De Vuono was also affiliated with the Calabrian mafia organization 'Ndrangheta, several BR members claimed that the weapons used were acquired through them. Of the 93 bullets fired during the assault, 45 of them came from one weapon. In a reconstruction of the assault done by Italian magazine l’espresso these bullets, which include the majority found in the bodyguards, were fired by De Vuono.

Another theory of the identity of the alleged marksman is that he was a German who was affiliated with the far-left terrorist group RAF. One witness from via Fani reported that about thirty minutes before the assault a man with a German accent told him to leave the area. How the assault was carried out was also similar to one conducted by the RAF.

The number of terrorists present for the assault is also disputed. Originally, during the subsequent trials, BR terrorists said nine people took part in the assault, but later changed that number to eleven. Alberto Franceschini, co-founder of the BR believes both of these numbers to be too low to kidnap such a high-profile figure.

Along with the theories of a marksman, there are also multiple theories about foreign powers aiding, or having a hand in Moro's kidnapping, the most notable of them being the U.S. This of course took place during the height of the Cold War, and the US was not particularly fond of Moro because of his hand in helping the PCI secure a seat in the government of a democratic country. One theory surrounding the assault is the presence of what some believe to be two CIA agents. Witness reports recall the presence of two unidentified men on scooters who watched the assault take place. At the time several American Secret Service agents were living in the city, not particularly surprising considering Rome is the capital of a major European country. However, these two men have never been identified, and so their presence remains a mystery.

Location of Moro’s Prison

The exact location of Aldo Moro's prison is unknown and has been the subject of much dispute. There are two likely locations where many believe he was held. The first is an apartment in Via Camillo Montalcini 8 in Rome. This is the location where Moro was eventually killed, in the parking garage of the building. The apartment in question had been owned by the BR for years and was subsequently abandoned after it was put under investigation.

The second likely location is considered to be on the seaside, though, no exact location has ever been mentioned. When Moro's body was discovered, traces of sand and vegetable remains were found in the car. Terrorists later claimed that this was planted on his body to mislead investigators as to the true location of his prison. However, investigators doubt that the BR would know that they would investigate such minor details. Subsequent geologist investigations of the sand found it must have come from an artificial river rather than a natural body of water. This has led many to believe that Moro was kept somewhere along the Tiber.

18 April: A seance, False Communication #7, and the base at via Gradoli

Several strange and controversial events occurred on April 18th. The first was the supposed announcement of Moro's death in the BR's seventh communication. According to the communication, Moro's body had been dumped in Lago Della Duchessa, a very small mountain lake northeast of Rome in the province of Rieti.

However, the Italian police found no trace of Moro's body under the lake's icey surface. One of the authors of this false communication was notorious forger Antonio Chichiarelli who was connected to the Banda della Magliana gang in Rome. Chichiarelli would go on to release more false communications from the BR before being killed in September of 1984 in mysterious circumstances. His death came before the truth about the false communications was fully disclosed.

The second event occurred that same day when the police discovered an apartment on Via Gradoli that the BR had been using as a base. Allegedly, the discovery was made when a neighbour had called the firemen because of a water leak. Inside the apartment, police found a flexible shower nozzle that had been placed on a toilet brush stand, with water being directed at a crack in the wall, along with over 1,000 pieces of incriminating evidence. These pieces of evidence included the Alitalia flight crew uniforms that the attackers had worn on the day of the assault. The apartment, number 11 at Via Gradoli 96, was the residence of Mario Moretti, considered the top leader of the Red Brigades. Moretti interrogated Moro almost daily and could have been tailed to find the location of his prison.

The seance

What makes this discovery particularly strange, however, is that authorities had reason to suspect this apartment weeks, and even years before the discovery was made. Moretti's apartment had been under observation for several years as it was also frequented by members of other far-left organisations. Then, on 2 April, 12 people, including future prime minister Romano Prodi, allegedly took part in a seance in the city of Bologna. Using a Ouija board, the group tried to contact the spirit world to gain information about the location where Moro was being held. The details of the alleged seance are widely disputed and there is reason to believe that it never did take place. Those who participated reported it was raining in Bologna on the day of the session, however, several accounts recall that there was no rain in the city that day. The session did however produce one interesting name, Gradoli.

Cossiga was made aware of the details of the seance by Prodi and investigators turned their attention towards the town of Gradoli north of Rome. Cossiga ordered 450 military personnel to conduct a thorough search of the town, but no evidence of any Red Brigade presence was ever found. The details of the search were also disputed by many witnesses who stated that the military personnel conducted a very brief search of the town. With the search yielding no results, officials discounted any credibility of the seance. However, Moro's wife Eleonora suggested that perhaps the name Gradoli was actually in reference to the street in Rome, but Cossiga insisted that no such street existed.

But of course, via Gradoli did exist, in a quiet neighborhood in the north of Rome, not far from where Moro was abducted. The neighborhood was home to many domestic and foreign secret service agents who used some apartments as safe houses. What makes the case even stranger is that authorities had reason to suspect via Gradoli because of suspicious activities being reported there as far back as 18 March. One witness reported to the police of three suspicious-looking men lingering outside of via Gradoli 96 as if checking who came in and who came out.

Another neighbor reported hearing strange noises coming from apartment 11 that sounded like the tapping of morse code, the police report on this is nowhere to be found. Eventually, authorities could no longer deny the existence of via Gradoli 96, and police were instructed to conduct a thorough search of the building. Police searched every apartment except number 11 because no one answered the door and neighbors all vouched for the inhabitant, a claim that some of them deny.

Years later it was revealed that DC parliament member Benito Cazora had been tipped off to via Gradoli thanks to contact with the ‘Ndrangheta Calabrian mafia organization while trying to find information on Moro’s location. Cazora was told that via Gradoli was a “hot zone” and reported this information to the police. Why the Italian authorities failed to act when they had plenty of reason to suspect Via Gradoli remains unknown.

P2, Gladio, Italian Intelligence Services, and the involvement of Foreign Powers

Propaganda 2 (P2) was a mysterious masonic lodge that was involved in several political and financial scandals during the 70s and 80s. P2 had a diverse group of members which included entrepreneurs, journalists, high-ranking members of right-wing political parties, and Italian police and military forces. Many have suggested that P2 had a hand in Moro's kidnapping and played a role in keeping the location of his prison secret.

This largely stems from the discovery of a list of lodge members on 17 March 1981. The list revealed just how great and diverse a presence the lodge had, as many of their members occupied powerful positions. These include: Giuseppe Santovito, director of SISMI; prefect Walter Pelosi, director of CESIS; general Giulio Grassini of SISDE; admiral Antonino Geraci, commander of SIOS; Federico Umberto D’Amato, director of the Office of Reserved Affairs of the Ministry of the Interiors; generale Raffaele Giudice and Donato Lo Prete, respectively commander and chief-of-staff of the Guardia di Finanza; and Carabinieri general Giuseppe Siracusano. Carabinieri general Siracusano was the one responsible for all the roadblocks around the city during the time Moro was imprisoned.

Considering the BR likely planted the cars used in the assault over the course of three days right after it had taken place is strange, to say the least. Especially considering they did so in such a heavily guarded section of the city, and police never picked up on it. This could be an indication that Siracusano and P2 had a hand in the whole affair. On the day of Moro's kidnapping, some of the most powerful members of P2 met at the Hotel Excelsior in Rome. Upon leaving the meeting, Gelli proclaimed "the most difficult part is done" supposedly in reference to Moro's kidnapping.

Members of P2 were also present during the discovery of the base at via Gradoli. Weeks before the base was discovered, an informer for the SISDE and neighbor of Moretti Lucia Mokbel claimed she was hearing a ticking noise that resembled MORSE messages coming from Moretti's apartment. She informed police commissioner and P2 member Elio Coppa, however, when no one answered the door of the apartment, Coppa did not attempt to enter and investigate. It was later deduced that the noises coming from the apartment were likely from an eclectic typewriter, which many suspect Moretti was using to write the BR's demands and communications.

Another commonly held theory is that the BR had been infiltrated by several different foreign and domestic intelligence agencies. The most prominent organisations being the CIA, Israeli intelligence agents, and Organizzazione Gladio, a NATO-headed paramilitary group tasked with opposing Soviet influence in western Europe.

In 1990 it was disclosed that Camillo Guglielmi, a colonel of SISMI’s 7th division which controlled Operation Gladio, was present in via Stresa, near the location of the ambush when it took place. He admitted to being in via Stresa at the time of the ambush but stated he had been invited for lunch. This was later debunked as his colleague said he arrived uninvited and considering the ambush took place at 9:00am it was far too early to be arriving for lunch.

It also comes as no surprise that United States Republicans were not fond of Moro thanks to his involvement in the Historic Compromise. During the 1983 trial against the BR, Moro's widow Eleonora Chiavarelli stated that her husband was unpopular in the United States for this very reason. She alleged that Moro had been repeatedly warned by American politicians to stop disrupting the political situation established in the Yalta Conference and that he would be "badly punished" if he did not.

In 2005, former national vice-secretary of the DC Giovanni Galloni said that during a discussion with Moro about the difficulty of finding BR bases, Moro informed him that he knew of U.S. and Israeli intelligence agents who had infiltrated the BR. This allegation was echoed by none other than Alberto Franceschini, one of the founders of the BR. Franceschini stated that the BR had been infiltrated by Israeli agents as early as 1974, and also reported that BR co-founder Renato Curcio informed him that Mario Moretti would be an infiltrated agent. Franceschini and Curcio were both arrested in the mid-70s, after which Moretti took control and introduced a far more militarized approach to operations.

Role of Steve Pieczenik

Pieczenik also spoke about the political game that was being played amongst those that were searching for Moro. He said that those on the right "wanted the death of Moro, the Red Brigades wanted him alive, while the Communist Party, due to its hardline political position, was not going to negotiate." Cossiga's position in all of this was difficult. He wanted Moro alive but he was dealing with forces far outside his control. Pieczenik was also stunned by the number of fascists in the Italian intelligence service. He also declared that he was involved in the decision to issue the false "Communication #7" to push the BR to kill Moro. He did so once it became clear that Italian politicians were not interested in negotiating for Moro's liberation and hoped that killing Moro would delegitimise the BR.

Role of Carmine Pecorelli

Carmine Pecorelli was a notorious Italian journalist who wrote about the kidnapping of Moro in his magazine Osservatorio Politico (OP). Pecorelli allegedly had numerous contacts in the Italian secret services. The day before Moro was abducted, OP published an article that cited the anniversary of the assassination of Julius Caesar and mentioned the possibility that a new Brutus would appear in reference to the new Andreotti cabinet that was set to take power the next day. Some articles written during Moro's imprisonment suggest that Pecorelli knew of some of the unpublished letters. Pecorelli also suggested that there were two different factions within the BR, one intent on killing Moro, and one that wanted to negotiate for his release.

Pecorelli would later be murdered in front of his house on the 20th of March 1979, just over one year after Moro was abducted. Mafia informant Tommaso Buscetta stated in 1992 that Pecorelli had been killed as "a favor to Andreotti." It was alleged that Pecorelli had some sensitive information about Moro, including a letter from Moro.

The day of his murder, Pecorelli had written an article in which he hinted at the role of opera composer Igor Markevitch in Moro's kidnapping. Markevitch had housed several BR terrorists in his estate in Florence. His residence in Rome was on Via Caetani, where Moro's body was discovered. In the article written on the day he was killed, Pecorelli wrote about "the people's prison" in which Moro was held. In it, he mentioned a palace in the center of Rome with lions. Markevitch's palace in Rome had a bas-relief of two lions biting two horses.

Theories of Alternate Kidnapping

One last strange theory suggests that Moro was not present for the assault in via Fani. Journalist Rita di Giovacchino suggested that he had been taken prisoner by another organization and that the BR had only acted as a distraction. According to Giovacchino, this theory would explain the remark made by the first secretary of Moro, Sereno Freato, after Carmine Pecorelli was also found dead: "Investigate on the investigators of Pecorelli's murder, and would find the instigators of Moro's murder." The BR also used printing machines once owned by Italian intelligence, who Giovacchino considered the likely instigators of the kidnapping. However, this theory, like so many details of this case, remains shrouded in mystery.